Part

1

Complete

list of Joyce hatto recordings available

for purchase through MusicWeb

Joyce

Hatto THE RECORDINGS

‘She makes music without

imposed superlatives’

Frank

Siebert, Fono

Forum, June 2004

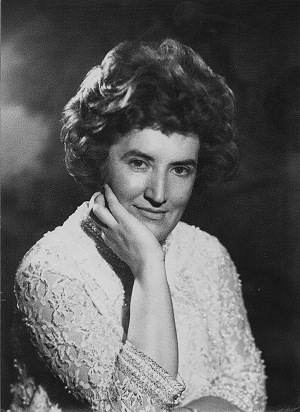

©

Vivienne of London 1970

©

Vivienne of London 1970

Joyce’s recording career

divides broadly into two periods, the

second comprising the Concert Artist

releases. Of the differences of personality

and person between the two, she says:

‘When I was young,

people told me I had two speeds, quick

and bloody quick.’ [RD] In Warsaw,

and later in London, I had opportunities

to play many times to Zbigniew Drzewiecki

[…] he was always anxious to clean away

any excessive rubato that might

have crept into my playing. For Drzewiecki,

the composer’s text was his bible […]

at this time [late ’50’s, early ’60s],

my playing had [arguably] become excessively

expressive and was in need of correction.’

[JH/Chopin]

Early Ventures

Scanning the British

Library Sound Archive suggests a player

going down the critically-derided Eileen

Joyce/Serge Krish road, mixing favourite

concertos (Rachmaninov Two – in Hamburg

with George Hurst, in those days principal

conductor of the BBC Northern Symphony

Orchestra), lightweight film pot-pourries-cum-pastiche,

and the then dangerously cross-over

jazz ‘decadence’/classical sacrilege

of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue

(with George Byrd – again Hamburg).

Like Sergio Fiorentino, her one-time

stable-companion, she seems happy to

have contented herself for years not

so much with the majors as any budget

label who would offer her a platform,

whatever their provenance or potential

(Society, Delta, That’s Classical, Saga,

Boulevard). With Gilbert Vinter and

the London Variety Theatre Orchestra,

she recorded an LP for Boulevard including

Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, Jealous

Lover, A Tale of Two Cities,

Dream of Olwen, Cornish Rhapsody,

Legend of the Glass Mountain,

and Richard Addinsell’s obligatory Warsaw

Concerto – released in 1959. Weightier

material (if still gramophonically low

profile) came from Delta (Mozart’s K

453 with the London Classical Ensemble

under David Littaur). And to some extent

Saga. (Though rumour has it that Saga

destroyed tapes of two Beethoven-Liszt

Symphonies, Nos 8 and 9 – along with

some Fiorentino Bach.) In 1962 she recorded,

abortively, Liszt’s Seven Hungarian

Historical Portraits - which she’d

resurrected in concert in 1958, but

then felt the need to revise in the

light of ‘closer acquaintance with the

original manuscripts and alternative

sketches’ (premiered at the Wigmore,

26 October 1972).

Under the direction

of Joyce’s husband, William Barrington-Coupe

(her unsung producer), Revolution Records

steered her in a more esoteric, up-market

direction, not least with the release

of Bax’s Symphonic Variations which

launched the company in 1970 (RCF 001),

and his First and Fourth Sonatas. Constant

Lambert, too, went into the can. Notwithstanding

such repertory, comparatively little

of the Joyce of those days was to give

any indication of the flood, the phoenix-like

re-invention of herself, to come twenty,

thirty years later – following her withdrawal

from the concert stage and the silence

of the ’80s.

Concert Artist

One of the few post-war

UK independents still in business, ‘a

company run by musicians and music enthusiasts,’

Concert Artist [http://www.concertartistrecordings.com/]

was established by William Barrington-Coupe

in 1952 – ‘with the basic objective

of providing a sounding board for young

British talent […] neglected by the

[…] major record companies who held

sway some fifty years ago […] The small

size of the young label, many distributing

problems, and the open hostility that

confronted the company,’ their publicity

reads, ‘did not prevent it from adopting

a very positive attitude in promoting

unusual repertoire. It scored a number

of notable "firsts" in those

early years […] premiere recordings

of unusual works by Beethoven, Bartók,

Chopin, Elgar, Handel, Liszt, and many

others [finding] their way into […]

record collections [around] the world’.

Befitting a London past working with

Eileen Joyce, Fiorentino and Lazar Berman

- besides joining forces briefly with

the futuristic, sonically pioneering,

finally crazed Holloway Road producer

Joe Meek (1929-67), forming Triumph

Records in January 1960 - Barrington-Coupe

is a man who keeps up with technology.

He may work in the classical industry

– but to his ears (placing him in the

Seymour Solomon ‘I had an ideal sound

in my ear’ tradition: ‘there’s only

one way to do a recording […] produce

it yourself’) a natural, distinctive,

pedigree sound doesn’t necessarily have

to be one classically generated or schooled.

The Cambridge engineer Roger Chatterton,

responsible for Concert Artist’s re-mastering

programme, comes, for instance, from

a touring, gigging background working

with bands and groups in Britain, Europe

and the US. At best such experience

releases a physical dimension and imaginative

aura in Joyce’s recordings freed of

the closed parameters frequently associated

with classical purists.

René Köhler

A survivor of the Holocaust

gone missing in the murky wastelands

and unspoken history of Cold War Europe,

René Köhler (1926-2002)

conducted Joyce’s concerto recordings

during the ’90s, directing two ad-hoc

studio orchestras – the National Philharmonic-Symphony

and the 68-strong Warsaw Philharmonia.

‘Brought up in Weimar,

René was a pupil of Raoul

Koczalski [1884-1948, via his teacher

Mikuli a direct descendent by tutelage

of Chopin]. He was precocious, playing

both Chopin concertos by the age of

ten. In

1936, through Koczalski’s recommendation,

he briefly continued studying music

at the Jagiellonian University of Krakow.

Failing to be awarded a government scholarship,

he moved to Warsaw. In the Polish capital,

unable to join the Conservatoire

because of his Jewish faith, he studied

privately with the pianist Stanisław

Spinalski. In 1940 his left hand was

crushed irreparably by a young German

“officer”, so-called. He survived the

Ghetto but in the summer of 1942 was

deported to Treblinka [one of

around 300,000 "resettled"

over a period of 52 days between July

and September]. Here [or in the vicinity

- one of less than a hundred believed

to have survived] he was found by the

advancing Red Army [circa 1944].

Unimpressed by his mixture of Polish/French

and German-Jewish stock, his Soviet

interrogator sent him on a train heading

East for a labour camp - where he remained

from 1945 until 1970. Given his freedom,

he returned to Warsaw, with the help

of a Russian friend, to try and sort

out his family property. He learnt that

a small-holding, confiscated by the

Nazis in 1940/41, had been allocated

to a German family as part of a "Resettlement"

scheme. Exacting "justice"/revenge/retribution

on the resettled family in 1945 (they

were killed), the new Polish government

then impounded the place, later to form

an integral part of a Communist Party

Commune. René found that the

Polish authorities refused to recognise

the name "Köhler" as

having Polish associations. Their Soviet

counterparts meanwhile denied they’d

ever "captured" or held him

prisoner. The East Germans were not

interested in the case, claiming that

the Köhlers had left the Weimar

area in 1936 of their own "freewill".

In fact they’d fled, an old professor

at the Hochschule (whose son was a Nazi

Party member) having warned them, at

personal risk, that they should leave

Weimar since all Jews were to be rounded

up the following year to be sent East.

Three of the family had already been

murdered. René kept such things

to himself. He never desired any attention

from the media. Physically he was a

mess - probably why he used to add to

his age to account for his appearance.

He died from prostate cancer.’ [WB-C,

adapted]

Instrumentarium

Joyce recalls that

her first proper piano as a child in

the mid-’30s was a Leipzig Blüthner

grand bought by her father. Following

a liking for vintage pre-war instruments

shared with Michelangeli and Zimerman,

her present one, used almost exclusively

on the Concert Artist recordings, is

a 1923 Hamburg Steinway D, Serial No

217355:

‘[…] an elderly

piano but one with a naturally beautiful

sound. Completely restored, it offers

a big sonorous tone without the edgy

clangour and hard-edged sounds of the

modern Steinway with its pressed new-type

frame. Originally it was in the old

HMV Studios in Abbey Road and was used

for classical sessions. Many distinguished

pianists recorded on it. When Abbey

Road decided that a new Steinway was

essential, they decommissioned it. Fortune

shone on us, we followed up some leads,

and discovered it down in Sussex.’

[WB-C]

The Concert Artist Collection

Joyce stopped playing

in public in 1979. Hospitalisation,

near-death encounters, and alternative

therapies followed - to become the pattern

of her existence. She returned to the

studio, 3 January 1989, playing Liszt.

Since then she has maintained an annual

recording schedule, reaching a peak

of intensity in 1997-99. No discernible

pattern or progression of repertory

is apparent. Rather a mêlée

of works, of stark emotional juxtapositions,

of dramatically differing linguistic,

spiritual and style states seemingly

as the mood and impulse takes her, of

projects begun, taken up again, or completed.

In the five days between 4th

and 8th January 1998, for

example, she ranged from Chopin (four

ballades) and Beethoven (Hammerklavier)

to Prokofiev; in the corresponding period

the following year, 3rd-7th,

from Saint-Saëns (Fourth Piano

Concerto), late Beethoven, Mendelssohn

(the two piano concertos [CACD-9070-2]),

Rachmaninov (B flat minor Sonata [CACD

9079-2]) and Schumann to Schubert (last

sonata) and Liszt, and back again to

Beethoven (middle period sonatas). Prodigious.

Marathon feats: the

Hatto hallmark. As Cortot could do Chopin’s

Préludes and two books

of studies at a sitting, so she could

do a Chopin recital tour playing 26

dates in 34 days (1958-59). Or all the

Field nocturnes before tea, and Chopin’s

after dinner (1953). Assuming correct

documentation, five of her studio visits

strike me in particular (changes of

sound or microphone position between

works notwithstanding), Joyce ostensibly

doing in a day what others would need

two or three for. Contemplate the magnitude,

the intellectual grasp, the aesthetic

response, the sheer pianistic stamina

and concentration required:

6, 7 January 1995

Liszt Italian Operatic Transcriptions,

including Hexaméron,

Niobe,

Norma

and Sonnambula [CACD

91112, 91122] Four late Mozart

sonatas,

K 533/494,

545, 570, 576 [CACD 9055-2

4 January 1998 Chopin

B minor Sonata [CACD 9043-2].

Beethoven Hammerklavier

[CACD 8009-2]

14 October 1998 Schubert

Sonatas in A minor, C minor, D 845,

958 [CACD 9064-2]

16 March 1999 Mussorgsky Pictures

at an Exhibition [CACD 9129-2].

Balakirev Islamey [CACD

9195-2]

5 September

2003 Chopin Op 10 Études

– a 75th birthday

fest in the middle of

Chopin-Godowsky

sessions [CACD 9147-2, 9148-2]

- impossible, many

cynics would uphold.

Joyce comes from the

tail-end of a generation (the 78 rpm

one-takers) for whom preparing meticulously

for a recording was increasingly the

norm. Broadcasting-style, allow yourself

a couple of complete takes, the odd

patch; expect to get the right result

(note accuracy, interpretative overview)

in the minimum of time; don’t assume

endless hours on tap. The greater the

luxury of time, the greater the chance

to fuss over passing imbalances or imperfections,

to stultify a sense of performance.

This is not Joyce’s way. From the beginning

she was a rapid learner, mindful of

the need to get style, notes and logistics

right as a first priority. Working on

their Rhapsody in Blue recording,

George Byrd remembers how ‘very impressed’

he was with her eagerness to explore

with [him] the special American style

of the work of George Gershwin, and

her quickness in integrating these elements

into her playing - we had only a few

sessions. The results of our collaboration

were a rewarding experience.’ [GB] From

the track-listings of her CDs, most

works or cycles are finished at a sitting

or during a run of consecutive sessions/days.

Occasionally though she will set aside

a project to be continued or completed

at a later date. Prokofiev’s War

Sonatas, for instance, were not to be

finally tidied-up until six years after

they were first tackled. The Liszt Sonata/Rhapsodie

espagnople album, begun in 1989,

only reached completion in 1999 [CACD

9067-2]; the Transcendental Studies,

started in 1990, in 2001 [CACD 9084-2].

Maintaining consistency of idea and

interpretation over a lengthy period,

with a sound envelope to match, doesn’t

seem to pose a problem.

Assessing most pianists,

the critical instinct is to refer to

others, to make judgmental comparisons

- invidious as the process is. With

Joyce I find myself rarely tempted to

so do. Her authority is her own. Even

when some of her decisions, her occasionally

urgencies, are not to my taste, there’s

a rightness, an honesty,

to her recorded playing, that compels

of its own. I feel in safe hands, I

know her pianism won’t let down the

composer, or her sense of occasion the

listener. Tone, phrasing, projection.

Articulation, pedalling, dynamics. Style,

short-term shaping, long-term architecture.

The ability to speak in music - eloquently,

rhetorically, passionately, murmuringly.

Such are the parameters she has honed

to become the heart of her art. Her

purling professionalism, the glitter

of her cadenza and fioritura,

the tenderness of her quiet loving,

her fearlessness of emotional display,

remind me of the old-time Slav romantics,

the great musicians, who shaped my values

as a student.

©

Vivienne of London 1970

©

Vivienne of London 1970

A Personal Selection

ALBENIZ Iberia. CACD

9120-2

3

January, 5 January 2003. Concert Artist

Studios, Cambridge. Review

William Hedley

Like the later Debussy

Préludes, Iberia

tests a pianist’s technique,

imagination and dynamic resources. Joyce

is no exception in finding it hard to

grade her range from fffff

to ppppp (El Corpus

en Sevilla) – de Larrocha comes

no way near – but she gets to the heart

of the music, its evocacíon

and mercurialism, better than most,

even if her breathing and nuancing is

different from the Spanish school. The

bright passages glitter with hard heat,

the languorous hold-backs, the voice-breaking

triplet turns, the sensual basses, the

double-octave-spanned ‘Andalusian’ unisons,

recline in dusky coolness, Moorish scents

on the wind. Gypsies, workers, dancers,

drinkers, singers, ardent lovers, clattering

courtyards, stories behind closed shutters.

I am reminded of Laurie Lee’s Spain.

Playing to her strengths, Joyce thrives

on the plentiful pedal (and non-pedal)

markings. The contrasts of tight rhythm

and flexible rubato, the sudden

accents and chest-voice cante hondo

melodies, the guitar and high percussion

colouring, the bouncing staccati,

the mood changes, are well integrated.

And though she shies from indulging

the composer’s caesuras and die-aways,

she makes good sense of his many swellings

and contractions of time. Only in trying

to make some of his repetitions of theme

and episode interesting – de Larrocha’s

sphere - may she be found sporadically

wanting.

BAX Symphonic Variations

in E. Guildford Philharmonic Orchestra/Vernon

Handley.

CACD 9021-2

ADD

3 May 1970. EMI Abbey

Road.

Master of the King’s

Music, Bax was Joyce’s musical passion

in her teens and early twenties. Knowing

his romantic weakness for pretty young

women, perhaps she was his too. Between

them, however, stood the protective,

possessive Harriet Cohen. James says

as much in the opening paragraphs of

his interview - detailing circumstances

some time between 1950 (when Joyce acquired

a photocopy of the original manuscript

of the Variations from the publishers,

Chappell, with corrections in Bax’s

hand) and 1953 (the year of his death).

‘It was Sir Arnold

Bax who first brought Joyce Hatto to

my more active attention. I had seen

the name in the concert columns but

it did not register until I found myself

in the Nags Head, Holloway, supping

with Arnold after attending a rehearsal

of one of his orchestral works by the

Modern Symphony Orchestra at the Northern

Polytechnic […] my ears were kindled

when Arnold imparted that Joyce Hatto

was to tackle his Symphonic Variations

with the Modern Symphony. Sir Arnold

was positively gleeful that Miss Hatto

had actually asked to play his mammoth

creation and not cajoled into it by

his publishers. This had obviously endeared

the young pianist to the composer from

the off. He confided astonishment that,

when playing the piece through to him

in the Blüthner Studios [Wigmore

Street], she could not only play the

quite horrendously difficult piano part

but actually understood it […] Arnold

was delighted that the pianist had eschewed

the simplified version that he had prepared

for Harriet Cohen and had reverted to

his original conception […]

It was then a strange

coincidence that three days later I

should receive a ticket and a leaflet

announcing a recital given under the

auspices of the [recently founded] Liszt

Society. Now a Liszt Recital was a rarity.

For a pianist to offer the Twelve

Transcendental Études and

to precede these by the composer’s earlier

Twelve Études Op 1 seemed

almost foolhardy. The coincidence was

that it should be the same Joyce Hatto

to perform this feat. This was a Lisztian

event not to be missed. After the recital

I was introduced to this young woman

who had so charmed Sir Arnold. I congratulated

her on her programme and chatted about

the several late pieces she played as

unusually interesting encores [collected

in Vol 1 of the Liszt Society publications,

1951]. Of course, I had to mention that

I was looking forward immensely to her

playing the Bax Symphonic Variations.

There was a definite tremble on her

lower lip and I realised that this was

a sore subject. I could only glean that

the performance had been cancelled as

some "strange circumstances"

had arisen. No additional explanation

was offered and I did not to press her

further […] the journalist in me, as

much as my disappointment. […] induced

me to telephone Sir Arnold the very

next morning. I immediately reported

my conversation with Joyce Hatto and

asked him what the "strange circumstances"

could be. "Harriet" was the

only word spoken and the line went dead.

I should have guessed at once that Harriet

Cohen figured in these "strange

circumstances" as her possessiveness

with any music, composer, or musician

who happened to cross her path was known.’

[BJ]

Charting a chain of

mystic experiences from Youth: ‘Restless

and Tumultuous’, through Strife and

Enchantment, to Triumph: ‘Glowing and

Passionate’, the Symphonic Variations

were written for Cohen, who gave the

premiere with Henry Wood at the Queen’s

Hall, 23 November 1920. Joyce’s landmark

public performance with the Guildford

Philharmonic and ‘Tod’ Handley, at the

Civic Hall, Guildford, Saturday 2 May

1970, was judged the first complete

account of the work in fifty years.

That it had to take place after

Harriet’s death was because ‘Harriet

[had been] determined to block any performance’

[JH/Bax]. Justifying Sorabji’s early

faith in the piece – ‘the finest work

for piano and orchestra ever written

by an Englishman’ (Around Music,

1932) - the recording, enthusiastic

and pianistically brave, proved a pioneering

two-and-a-half-session 46-minute trail-blazer.

Concert Artist’s 2003 reissue digitally

restores and re-edits the original analogue

master. That it leaves un-rectified

the ensemble/blending problems of a

1970 home-counties week-end orchestra

in rehearse-and-record mode - despite

the experience of William Armon leading,

two prior concert rehearsals, and section

leaders/rank-and-file members drawn

largely from the main London orchestras

- scarcely matters. As a turning-point

in Joyce’s life, her ‘greatest ambition’,

throwing down the gauntlet to the BBC/Glock

camp and the British anti-tonalists

of the ’60s and ’70s, helping, Lyrita-style,

to blaze the trail for the Chandos/Hyperion

‘English’ phenomenon to come, this is

a historic CD of significance.

BEETHOVEN Sonatas Opp

109, 110, 111. CACD 8010-2

18

September 1994; 3 January 1999. Concert

Artist Studios, Cambridge.

‘Unconventional, experimental’

music of’ ‘lofty spirituality’ peopled

by ‘many different characters’ was Hugo

Leichtentritt’s postcard landscape of

Beethoven’s late sonatas. Ranging ‘from

inferno to paradiso,’

he told Harvard audiences in the thirties

(Music, History, and Ideas),

‘their magnificent cosmic visions (Opp

106, 109, 111) have passed beyond the

appassionato and the Titanic

phases into metaphysical depths, mystic

regions of a world beyond, [while] intermezzi

of incomparable lyric beauty and intimacy

of utterance (Opp 81a, 90, 101, 110)

tinged with melancholy sing of the enchanting

loveliness of the terrestrial world.’

Op 111, decreed Thomas Mann (Doktor

Faustus), ‘brought’ the (classical)

sonata as a form to an ‘end’ – ‘it had

fulfilled its destiny, reached its goal,

beyond which there was no going’. Pondering,

manifesting such truths, Joyce’s Beethoven

cycle is a vital document. Not to devalue

her Bach, Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninov

and Prokofiev, I wonder if it may not

turn out to be her most lasting achievement.

The late sonatas - in the past a measure

of maturity and greatness, today increasingly

a hunting ground of the young - produce

a typically direct response from her.

She lets them speak on their own terms.

Without to-do, she draws our attention

to the fact that in Op 109 the first

movement (strikingly voiced and integrated)

is ‘vivace’ but ‘ma non troppo’

– ‘noble, calm, but dreamy’ (Czerny);

that the theme of the finale is ‘molto

cantabile’ not ‘andante’ or ‘adagio’.

With Op 110 she lets us know that the

opening movement is no more or less

than ‘moderato cantabile’ – besides

establishing its 3/4 pulse even before

a note has sounded: there’s not a hint

of metric instability about the first

two bars. When subsequently she floats

the demisemiquaver arpeggio ‘roulades’,

she does so aware that to Beethoven’s

disciples they were ‘extremely light,

and by no means brilliant’ (our

italics). That the ten syncopated G

major chords of the fugal finale, bars

132ff, need not be held back

in their (open-ended) crescendo

but can be taken to an anguished una

corda fortissimo goes with

the ‘all out’ nature of her interpretation.

Op 111, travelling its Romantically-charged

journey from dissonance to concord,

black forte G minor diminished-seventh

homelessness to white pianissimo

C major repose, primeval darkness to

celestial light, earthly passion to

heavenly pæan, receives a physical/hallowed

performance of Ninth Symphony/Missa

Solemnis ambience. Not always note-smooth

agreed. But, relatively, how many pianists

play like this? And, since Solomon,

how many British ones?

BEETHOVEN Sonatas Opp

7, 106 (Hammerklavier). CACD

8009-2

2

August 1995; 4 January 1998. Concert

Artist Studios, Cambridge. review

Jonathan Woolf

When I was learning

Op 7 in the early’60s, the semiquavers

of the first movement and the twisting

demisemis of the rondo in particular,

how I wish Joyce’s performance had been

before me. This is a classic traversal,

varyingly brilliant, playful, and dark

(third movement trio). The phrasing

and touch, the gracefully gauged pedalling,

the chamber-like approach to texture,

dots and slurs, is a masterclass. Likewise

the gran espressione of the thee-page

Largo, with its quasi-pizzicato

‘cello’ accompaniment, and its ‘spoken’

delivery of turns and ornaments high

above a sonorous bass. ‘Sing through

your rests’ Plunket Greene used to advise

(quoted by Tovey in the 1931 Associated

Board edition I learnt from). Joyce

does. The Hammerklavier flows

without posturing. Plenty of grit and

tension, a sweeping sense of form and

argument, yet free of angst when

the going gets tough. Joyce takes its

puissance course in her stride, rarely

forcing the issue, preferring leanness

to corpulence. Sustain the Adagio

she does, but by only the slightest

of margins, preferring the music to

breath naturally rather than become

embalmed in some sepulchral tomb. Here

‘the player,’ Czerny says, must call

forth the whole art of performance,

in order that the hearer may not become

fatigued from its unusual length. And

yet […] the highly tragic and melancholic

character of the whole must be faithfully

preserved.’ Managing such balancing

acts is Joyce’s speciality.

BEETHOVEN Sonatas Opp

49, 53 (Waldstein), 57 (Appassionata).

CACD 8007-2

7

January 1999; March 2004. Concert Artist

Studios, Cambridge.

For Joyce it’s critical

that all music - big, small, complex,

simple, greater, lesser – receives complete

attention. Here we have the ‘easy’ Op

49 set given connoisseur treatment,

plumbing unsuspected depths. Not something

tossed-off but seriously considered

- and beautifully rounded tonally. The

Waldstein and Appassionata

she invests with pulsating symphonic

direction. These are big performances,

tightly reined. In the first movement

of the Waldstein she offers,

like Brendel, a simple lesson in how

to maintain tempo and tension: don’t

slow down, don’t introduce spurious

rits, follow, trust, the

composer. The lead-back to the exposition

repeat of the first movement, the point

of recapitulation (following a re-transition

crescendo boiling with Fourth

Symphony energy), the start of the coda,

are superbly controlled. Don’t be fooled

by the apparent matter-of-factness.

It’s all been rigorously thought out.

These passages are far from easy to

bring off. The weighting of the finale

Introduzione is profound, the

paused right-hand sf G

at the end pregnant with suspended suspense.

The rondo itself is a high-German painting

of romantic mist, pedalled scales and

sudden bouncing, clarifying staccati

(bars 55ff et al), fierce ‘Turkish

music’ minore, thrilling toccata,

gliding octave glissandi, and

prestissimo white C major tumult.

A grandioso view of a landscape

one cannot afford to ignore. The Appassionata

is no less imposing, if more flexible

towards matters of tempo shifts and

phrasing/architectural ritardandi.

The first movement holds together compellingly,

with an arresting mix of strong dynamic

contrasts and ‘wet’ and ‘secco’

attack to highlight the formal rhetoric.

Classic refinement, pin-point clarity,

and subtle emphases (for instance not

always stressing down beats, or leaning

off the dynamic) spread a golden veil

across the Andante ‘divisions’.

Wild Furies, roaring winds, envelop

the finale – yet with every branch,

each scattered leaf, naked to the microscope.

Rarely have I come across such discipline,

architectural foreground or clarity

of harmonic underlay. One of the great

Beethoven recordings.

BRAHMS Piano Concertos

Nos 1, 2

National Philharmonic

Symphony Orchestra/René Köhler.

CACD 8001-2

4 March 1992 [No 2];

4 June 1995 [No 1].Concert Artist Studios,

Cambridge;

St Mark’s Church, Croydon.

Reviews:

Concerto 1 Jonathan

Woolf Concerto 2 Jonathan

Woolf Christopher

Howell

Boldly projected, structurally

focussed, Joyce’s Brahms, concerted

or solo, is muscular, handsome more

than beautiful, with a tonal quality

to match, mountain rugged fortissimo

rather than salon refined piano.

She digs deep into the keyboard, Köhler

into the bedrock of his orchestra. Massive

textures, pugilist brass, intense melodic

lines and an upfront dynamic range create

a Heil Deutsche Romantische sound

from an epoch aeons before ‘period’

cleansing came on the scene. The D minor,

fairly ambiently recorded (to the advantage

of the piano if not always the orchestra),

is as sturm und drang

as you want, the whole built on a foundation

of harmonic sign-posting and bass line

progressions, Brahms’s tussle between

classical mind and romantic heart sharply

delineated. The adagio is simple,

direct, manly, finding benediction in

a closing piano cadenza and orchestral

amen of deep spirituality - slower

than Gilels but not burdened by the

fact. The rondo fairly takes off (erring

on the brisk side, Joyce’s view of allegro

non troppo, here and elsewhere,

has a tendency to minimise the ‘non

troppo’ caution), but climaxes in a

thrilling meno mosso impelled

forward by menacingly treading reed

woodwind, focussed drum, and dotted-rhythm

cellos. The deliberated first movement

of the B flat (recorded earlier) favours

the 1972 Gilels re-make direction –

18:40 against his 18:22. Only the andante

is quicker to any significant extent

– by 6.6%, 13:11 against 14:07. The

introduction sets a large stage, the

piano glowing into B flat major resonance,

each note picked and placed. Neither

scherzo nor finale are that preoccupied

with playfulness or humour, going for

serious drama and low-octave thunder

instead. Only in its cello/clarinet/piano

interlacing, does the slow third movement

embrace a softer, warmer vision - Joyce

the chamber musician, happy to listen

and take a back seat when necessary

(cf Tchaikovsky Second Piano

Concerto, slow movement, original version

[CACD 9085-2]). Performances addressed

to northern warrior gods. Necessary

to experience once in a while.

CHOPIN Waltzes Nos

1-20. CACD 9042-2

2

January 1992. Concert Artist Studios,

Cambridge. review

Jonathan Woolf

This collection offers

the standard 15 of most editions, plus

four posthumously published numbers

and a throwaway in F sharp minor attributed

to Chopin, published in 1932, for which

Joyce has long had ‘affection’ even

though it may be spurious. Her playing

is elegantly chiselled, old world perfumes

surrounding the music to create cameos

and sighs not of our age. Fine pianism

and feeling (unfashionable word). Readily

distinctive is the shaping and signing-off

of cadences, one of Joyce’s telling

signatures as a pianist. Luscious tone

and graded left-hand support throughout,

sometimes veritably pizzicato.

Subtle rhythmic buoyancy.

CHOPIN Mazurkas Nos

1-57. Vol I CACD 9116-2; Vol II CACD

9117-2

Begun

15 March 1992. Completed 27 April 1997.

Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge.

reviews Christopher

Howell Jonathan

Woolf

‘Monsieur Cortot’s

involvement with the Chopin Mazurkas

was extraordinarily deep and intensely

personal. His ideas […] struck a deep

chord with me. He felt Chopin had embedded

his own and Poland’s tragedies in each

and every one of them. As I had always

thought, from early childhood, that

life and nature itself was a great canvas

of tragedy, I was a sponge eager to

soak up more of the same from him.’

[JH/Chopin] I’ve returned frequently

to these discs, as evocative a rendering

of elusive music as one could wish for.

Joyce understands their femininity,

yet knows their manliness too. And is

at one with their psyche. ‘Coquetries,

vanities, fantasies, inclinations, elegies,

vague emotions, passions, conquests,

struggles upon which the safety or favours

others depend, all meet in this dance’.

The words of Liszt, prefacing the booklet

notes. Progressively, the playing travels

an extraordinary journey, from early

forthrightness to late intimacy, youthful

flirtation to exile dream, rough gesture

to high finesse. How Joyce inflects

this, taking us with her, is remarkable.

No hot-house contrivances here, no Rubinstein/Malcuzynski

parody - just notes, phrases, syncopated

accents, direct dynamic lighting and

a pinch of rubato drawn from

life and listening. Joyous, poetic,

sad. ‘The collective sorrow and tribal

wrath of a down-trodden nation’. ‘Dances

of the Soul’.

CHOPIN Four Rondos.

Four Ballades. CACD 9038-2

16 June 1992; 6 January

1998. Concert Artists Studios.

review Jonathan

Woolf

Period-infectious rondos,

playful without being gratuitous. The

ballades cohere well, independently

and as a group. That Joyce does not

over-state the introduction of the G

minor, nor over-do the tempo changes,

encapsulates her approach. WA Chislett’s

booklet notes comment that the Third

is ‘often murdered by speed-merchants’.

That is not Joyce’s way. The music unfolds

simply, left largely to speak for itself,

articulated with intelligence and authority,

the ‘I’ factor never to the fore.

‘Cortot’s thoughts

on the actual motivation driving Chopin’s

creative processes were quite different

to those of Arthur Hedley. Arthur Hedley

was quite convinced that Chopin was

quite different to the other composer-pianists

of the Romantic School in that he neither

sought, nor relied, on the stimulation

of the great written, pictorial or sculptural

works of art to feed his creative musical

inspiration. For example, Hedley scorned

the then widely held idea that Chopin

was influenced by the ballades of Mickiewicz

in connection with his own instrumental

ballades, whereas, Alfred Cortot was

quite firm in his belief that Chopin

was completely influenced by Polish

Literature, Art and Culture, [that]

the underlying seam of sadness in his

music was as much due to his personal

unhappiness as to the constant news

of […] sad events [arriving] so regularly

from his native Poland.’ [JH/Chopin]

CHOPIN Piano Concertos

Nos 1, 2

Warsaw Philharmonia

Orchestra/René Köhler. CACD

9082-2

5/6 October 1994. Watford

Town Hall. review

Jonathan Woolf

18-21 October 2005.

Soaked though I may be in the turn and

glitter of these works from the twelve

finalists of the latest Warsaw Chopin

Competition, I find it enlightening

to return to Joyce’s appraisal, an Anglo-Polish

collaboration of many-layered insights

and distinctive personality whatever

the occasional divergencies of opinion.

Playing Chopin she’s a very different

artist, another pianist even, from the

one met in Brahms – still the same force

and clarity of finger-work but more

of a colourist with time to inflect

and declaim phrases. On balance the

E minor Concerto (No 1) comes off best,

a reading of sensitivity and sensibility

to place next to Rubinstein, Pollini

and Gilels. The F minor takes time to

settle, Köhler initially setting

a non-maestoso tempo at variance

with Joyce’s slower ground-pulse. Once

in accord, though, she flourishes, ‘throwing’

the notes and investing the running-passages

with as much melodic significance as

harmonic purpose. The plain-spoken larghetto

may not extract the ultimate poetry

or intensity others have found (to my

mind, interpretatively speaking, the

opening A flat arpeggio, even though

without dynamic marking, is not so much

a foreground marker as a definer, a

setter, of landscape), but that said

there are touches I would not want to

be without (the pianissimo delicatissimo

scale and expiring staccato at

bar 72 of the cadenza, for instance).

In the finale the alternations of folk

terpsichore and concert bravura

captivate as they should, natural air

and space being found to place the notes.

Especially felicitous towards the end

is the clarinet/piano cadence with

echo at bars 309ff (5:06),

a rarely done effect. The phrasing and

tone of the cor de signal at

6:50 defines enchantment.

CHOPIN 24 Études

Opp 10, 25. Trois Nouvelles Études

B 130

2nd recording,

75th Anniversary Edition.

CACD 9243-2

1 (Trois Nouvelles

Études), 5 (Op 10), 8 (Op

25) September 2003. Concert Artists

Studios, Cambridge.

More robust and dynamic

than the 1992 recording [CACD 9035-2],

less studio-managed, the post-production

a touch rough and short-winded around

the edges – but what an extraordinary

feat, poetically strong and frequently

electrifying. Even (huskily) vocal.

Here we have an artist at full throttle,

high on adrenalin, technique gleaming,

commanding a Rolls-Royce of an instrument

firing on all cylinders. The two C sharp

minors – Op 10’s glycerine blaze, Op

25’s infinite nostalgia - sum up the

zeniths of an amazing universe. Others

may be more leggiero in the lighter

numbers (the G flat pair, the F major

from Book I). More concerned with a

polished veneer - reminiscent of the

louder passages in the 2002 Brahms’s

Paganini Variations [CACD 9030-2],

the rush of hormones on the last beat

of bar 48 of the opening C major, cancelling

out the composer’s diminuendo

otherwise observed on Joyce’s earlier

recording, strikes an unexpectedly rude

accent. Few, though, better her glorious

bass lines in the A minor or C minor

from Book II, exceed her G sharp minor

thirds, or equal the deep anguish and

longing she finds in the middle section

of the E minor (same volume). The Trois

Nouvelles Études (in the

order F minor, D flat, A flat [1st

French edition, November 1840]) are

gems. ‘Never wishing to be outdone’

by students or peers, Joyce has had

these pieces in her ‘practicing routine

for over fifty years’. It shows. That,

and memories of Koczalski and Cortot.

‘When I first started

to learn the Chopin Études

as a young girl I […] used the Cortot

Edition exclusively [Paris: circa

1917]and made full use of all the additional

exercises that Monsieur Cortot provided

for mastering and developing the fluency

necessary to master the technical problems.

When, wonderfully, the moment came for

me to play these études to Cortot

himself [London, circa 1947]

I asked him, a little nervously, which

study he would like to hear first. He

picked up my copy, turned to the first

study in C Major, and tapped the page.

Like a greyhound out of the trap I bowled

into my performance. It was, I thought,

much too fast (I was nervous) but it

was only the phrasing and the sound

that occupied him. He accepted that

I had acquired the necessary technical

ability […] and could freely spend the

valuable time at our disposal on the

musical aspects of the pieces. "Encore",

he insisted, and I played the piece

again, a few more comments in my ear

[…] "Encore", and I charged

through those arpeggios once more. After

my fourth effort he sat down at the

second piano and played the whole study

through making comments as he played.

Cortot made the point that the French

word "grande" did not translate

well into English as the term "grande"

did not countenance an absence of elegance.

Faced with his performance, played with

such ease, such a beautiful tone, and

so many tonal variations, one could

only marvel. He constantly illustrated

from the keyboard […] frequently [playing]

illustrations faster, in some instances

much faster, than on his recordings.’

[JH/Chopin]

Cortot’s ‘programme’

for each study Joyce does not reveal.

Nor his ‘romantic "extra-musical"

thoughts’ – beyond saying that they

were ‘tied up more specifically with

his remarks on art and the particular

paintings on which [to an accompaniment

of English tea and walnut cake] he would

expound quite knowledgeably and quite

spontaneously during our expeditions

together to the National Gallery in

London’.

DEBUSSY Twenty Four Préludes.

CACD 9130-2

4 January, 16 March

2001. Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge

review Christopher Howell

These performances

reward for their articulation (legato,

staccato, tenuto especially),

dexterous action, harmonic clarity,

chordal voicing, and regularity of pulse

(according to Marguerite Long, Debussy

premiered Danseuses de Delphes

‘with almost metronomic precision’).

The showering dazzle and distant Marseillaise

of Feux d’artifice … the toreador-presenced

Spanish tableaux … the music-hall

turns … the ‘wooden’ ‘mechanical rigidity’

of Général Lavine,

eccentric (Debussy/Long) … the desolation

of Des pas sur la neige … the

ice-watered grandeur of La Cathédrale

engloutie ‘sound-years’ away … the

esoteric exotic intoxication of La

terrasse des audiences du clair de lune

… the lonely burial urns and calling

souls of Canope (frozen, unbroken

LH tenths). All repay listening. That

Joyce elects to ally Debussy with the

Liszt rather than Chopin tradition,

presenting him on a masculinised canvas

in bold, ‘orchestral’, colours (witness

the gong-like bottom A’s at the end

of the Baudelair inspired "Les

sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air

du soir"), won’t on the other

hand be to everyone’s taste, Gallic

aesthetes especially. Occasionally more

humour, more ‘feeling of musical purity’

(the Pre-Raphaelite La fille aux

cheveux de lin), more smoky ‘half

tint’ lighting (distinguishing mark,

contemporaries maintained, of the composer’s

own playing), would not have gone amiss.

Similarly, in some numbers, less literal

phrasing, more flexibility in moulding

the many cédez arrestments,

and greater attention to the softer

levels of the dynamic spectrum. One

of those recordings to learn from -

forcing you to re-examine the printed

page and evaluate contexts.

LISZT Italian Operatic Transcriptions

Vol II. CACD 91112

6 January 1995 (Hexaméron);

7 January 1995 completed 18 May 2004.

Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge.

Transcription. Liszt’s

word. Speciality of the 19th century

klavier eagles. Sphere of the

Golden Agers. A chance to don many mantles

- the pianist as singer, violinist,

dancer, conductor, organist, orchestra,

chorus, popular gathering. Liszt left

some of Romanticism’s most searing,

starry examples – caressing, singing,

and thundering his instrument into a

glittering, humming Catherine-wheel

of images and illusions. An instrument

that by his death in 1886 had become

a high-tension, high-octane, 88-note

iron-and-wood beast, over-strung and

tri-pedalled, the ‘Lord Byron of Music’

(Anthony Burgess). I’ve lived, loved,

played and written about the Hexaméron

variations ever since Raymond Lewenthal

stormed the world with them in the 1960s.

There are several promising to excellent

recordings available - as well as the

odd one or two, it has to be said, sounding

little more than a sight-read. Joyce’s

account is neither promising nor a sight-read.

She knows this music and its symposium

of composers intimately, and she’s steeped

in the style. Played to the melody rather

than the ornament, living the song rather

than the bravura, here is an

aristocratic, persuasively engineered

version - my only reservation being

the occasional prolongation of certain

fermati, rests or divisions between

sections at the expense of the onward

flow and adrenergic tension you’d get

in a ‘live’ concert situation. But this

is a minor quibble. The byword Norma,

Puritani and Lucia di Lammermoor

‘réminiscences’ find Joyce in

responsive mood, as lyrical or wild,

pianistic or operatic, as the moment

demands. A quality bird’s eye view of

bel canto plunder at its greatest.

LISZT Années

de Pèlerinage II (Italie).

Venezia e Napoli. CACD 9150-2

11/12

March 1996; 1 October 1999. Concert

Artist Studios. review

Christopher Howell

‘When one listens to

[Hatto] one hears luminous tone harnessed

to cast iron technique, a very special

eloquence and sense of characterisation

quite without exaggeration or ostentation.

Added to these rare qualities are the

alluring sonorities she evokes and the

reflective stillness she somehow seems

to compel of the music – as much as

the music compels it of her.’ [Jonathan

Woolf, MusicWeb]. Finely engineered,

this is a special disc, Joyce exploring

Liszt’s programmatic, impressionistic,

futuristic roads to create a gallery

of thoughtful, atmospheric pictures.

True even of the Dante Sonata

– a molten, impassioned, theatrical

experience, terrifying in its manic

moments, yet with time for long passages

of reflection, calm and beauty of tone.

‘Joyce’s reading

of the Dante Sonata is slower

than the modern norm [19 minutes compared

with around 16 to 18]. Busoni felt and

told Krish that it was really to sound

as it was in the hot cavernous depths

of hell where the moans and cries "echoed

out" and reverberated from the bowels

of Lucifer's Kingdom. Joyce is not one

for using the sustaining pedal as a

prop to her interpretation. In this

piece, however, she is less sparing

and takes Liszt at his word, endeavouring

to find the sound the composer wanted

and Busoni tried to teach. In her original

[unsigned] notes she wrote "Liszt

takes us by the hand and leads us down,

down, down into the depths and abyss

of a fearful place...".’

[WB-C]

Pianistically, that’s

exactly what she does. Incandescent.

Venezia e Napoli leads us to

sunnier places. Even so there’s a sadness

and longing in the shadows – a slightly

out-of-tune instrument adding its own

elegiac imagery. The slow maggiore

arias and tears of the Gondoliera,

Canzone (at 2:27) and Tarantella

(2:01), music to test a pianist’s bel

canto, yearn and pause, holding

onto time and life, to unspoken memories.

Joyce’s mastery, her glass-edged poise,

the mirror she looks into, stills the

listener.

LISZT Études

Vol II. CACD 9132-2

12

November 1998, 6 January 1999. Concert

Artist Studios, Cambridge.

The best of Joyce’s

Transcendental Studies [CACD

9084-2] make for compelling listening.

Feux follets, Ricordanza

and Harmonies du soir impress

in particular for their ‘breeding’,

technical finish, and fanciful poetry

(they were coached in the late-’40s

by Moiseiwitsch and Cortot). Correspondingly

fine is this disc, comprising the five

Concert Studies (published 1849, 1863)

and the familiar 1851 re-write of the

Paganini series. The playing

ranges from the mercurial (a stunning

Gnomenreigen, ideally Presto

scherzando) to the achingly poetic

(an Un sospiro reminiscent of

Lamond; the misting aroma of the top

D flat in bar 45 of La leggierezza).

The Paganinis are grand and technically

sweeping. No tempo concession is made

to accommodate the difficulties of the

octaves in No 2. The trills of La

Campanella whir like Levitzki’s,

leading to (aurally) one of the most

convincingly untroubled finishes I know.

No 4 finds the piano alchemised into

a violin, so remarkable is the touch,

dovetailing of hands, and detaché.

Christopher Howell (MusicWeb)

neatly defines the hub of Joyce’s Liszt.

‘With technical nonchalance but a complete

lack of any virtuoso fuss, [she] just

gets on with playing the pieces "straight",

like the good music they are. Whether

she learnt this from some past teacher

or whether her instincts led her this

way I know not, nor does it matter much.

She is in that royal line of Liszt interpreters

who believe this is great music and

is to be played as such. Now, what you

won’t get from Hatto is the sort of

filigree passage-work that makes you

gasp at the sheer crystalline evenness

of it all. Her passage-work is good,

but it is not part of her agenda to

parade its "goodness" as an

end in itself. In other words, if it’s

Liszt the circus-master you’re after,

you won’t get it. But if you have resisted

Liszt because of his showy image, then

these wonderfully musicianly performances

might make you change your mind.’ Absolutely.

MOZART Eighteen Sonatas.

CACD 9051/55-2 (5 discs)

2-3 January 1995

(Nos 1-5); 6-7 January 1995 (Nos

15-18); 16 February 1995 additional

material 3 January 1999 (Nos 10-12);

23-24 February 1995 (Nos 6-8); 17

April 1995 (Nos 9, 13, 14, Fantasy

K 475). Cambridge Artist Studios,

Cambridge.

Reviews Christopher

Howell Vol

1 Vol

2 Vol

3 Vol

4 Vol

5

Richard Dyer has spoken

of ‘an operatic vocality and fluidity’

informing Joyce’s 1995 Mozart cycle.

This set gives unmitigated pleasure,

the ‘ring’ of the piano, each dot and

slur, floating in a memorably warm acoustic.

More often than not one can sense if

a concert performance is going to be

good, bad or indifferent from the way

the first two notes or chords are attacked

and timed rhythmically. So it is here.

The way Joyce sets a phrase on its limpid

journey, how she allows the music to

breathe, argue and relax, the manner

of her slow movements, so expressively

curved and ornamented, can only promise

special experience. She delivers a marvellous

series of characterisations drawn from

opera, ballet, symphony, concerto and

song. French poise, Mannheim galantry,

Viennese graciousness. Civilised speech,

elegant figuration, toying humour. There

is nothing reduced, restrained or ‘period’-precious

about this Mozart. If the music suggests

Beethoven, that’s what you get, gran

espressione, weighty chording, heavy-boned

forte and all. If it conjures

an orchestra, a harmonie, that’s

a cue for an emporium of scarcely-pedalled

touches, voicings and colours. Bold

gestures release big dynamics: Hammerflügel

turned concert grand. Intimacies and

anguish, poetic beauties, moderate the

scale: Steinway turned Stein. Listening

to Joyce’s unfailingly frank pianism,

her gift to let the music ‘happen’,

I find no urgent need to go back to

the scores, happy to sit back and take

delight in the calm perfection and good

taste, the buoyancy of the moment, spread

before me like an 18th century

garden. There’s an abundance of Mozart

sonatas on disc, from the ultra veneered

to the ‘psychotically weird’. Free of

hang-ups, Joyce’s set is one to cherish,

good to have on the shelf alongside

Gieseking and Klien.

PROKOFIEV War

Sonatas Nos 6-8 Opp 82-84. CACD 9122-2

Begun 7 January 1998 (Nos 6, 7); 10

February 1998 (No 8). Completed 3 September

2004.

Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge.

review Jonathan

Woolf

Joyce discussed these

20th century beacons in Moscow

with Richter, who’d given the premiere

of the Seventh in 1943. Here are structurally

cogent, rhythmically tight readings,

rich in imagery and clarity of textural

voicing - rarefied, personally experienced

visions, from insidious marche militaire

to distant basilica bells, painting

an often poignant canvas. The ambient

recording does splendid justice to the

music, repetitive and secco chords

ricocheting off the acoustic, resonant

yet un-pedalled. However competitive

the market-place, from veteran masters

to young bloods winning their spurs,

No 7 is about as good as you’ll get,

a version thrilling and sensitive, magically

hued and toned. Joyce has no time for

the tom-tom percussiveness and spiky

breathlessness many players spuriously

bring to Prokofiev. Rather she seeks

out beauty of sound, length of phrasing,

colour and solitude. The dynamic range

is wide but unexaggerated. Her low B

flat octaves, richly over-toned, thunder

with a gravitas not forgotten

easily, her softly hued upper registers

whisper confessionally.

RACHMANINOV Piano Concertos

1-4, Paganini Rhapsody.

National Philharmonic

Symphony Orchestra/René Köhler.

CACD 9178-2, CACD 9219-2

17 March 1994 [Paganini

Rhapsody], 5 October 1996 [Nos 1,

4]. Watford Town Hall. 29 March

1998 [No 2], 10 July 1998 [No 3].

St Mark’s Church, Croydon.

Reviews Jonathan Woolf Concertos

1&4 Concerto

2 Concerto

3

There are many fine

individual beauties here, not least

the observantly detailed, dare one say

gorgeous, orchestral support, plenty

of air and space (if arguably not always

sufficient ceiling) surrounding the

players. Joyce and René breath

and phrase as one, with shared lines

and a mutual sense of climax. The ensemble

and precision attack, rhythmic pointing,

and clarity of dialogue, is often remarkable.

If the lyric passages stick in the memory

more than the extrovert virtuoso ones

(No 1, finale central episode; the variations

leading up to and including the D flat

eighteenth in the Paganini, freed

of sentimentality in its chiselled remembrance),

maybe it’s because these performances

are rich in period-experienced chances,

heart-on-the-sleeve risks, and ‘dated’

expressive devices (portamento,

for instance). I find it very easy to

live with No 2, relishing the sonorities,

the bigness, the intimacy, the dynamic

finesse (a breathtaking ff>p

at fig 25 of the slow movement), the

precision trills, the way C major is

colouristically and emotionally differentiated

between loving, gently sighing afterglow

(first movement) and knock-out post-Tchaikovsky

glory (finale). No 3 commands impressively

- from the child-like innocence of the

opening … through tumultuous first movement

cadenza (the longer and chordally tougher

of the two Rachmaninov provided) and

expansive, fragile cadenced, scherzo-fleet

intermezzo … to big-boned, arabesque-teasing,

imperiously perorated finale. No one

for a second seems in doubt of their

place in the drama. The Fourth (dedicated

to Medtner), an awkward Cinderella,

repays investigation, Joyce, like Michelangeli,

Demidenko and Marshev, making a strong

emotional and structural defence. Again,

one must admire her conductor. Highly

impressive, always fearless, these recordings,

released in 2002/04, equal or out-strip

much of the current CD competition,

newcomers not least.

RACHMANINOV Études

tableaux Opp 33, 39. CACD 9128-2

15

June 1996, 28 September 1999 (Op 33);

19/20 September (Op 39).

Concert Artist Studios,

Cambridge review

Jonathan Woolf

Form, it’s been said,

is ‘slow’ (to perceive), colour ‘quick’

(to recognise). In these seventeen pieces

Joyce gives us form and colour in equal

doses at equal speed. Spiritually at

home in the atmosphere and melancholy

of Russian music - Rachmaninov’s figurations

lying well under her hands, his sonorities

drawing the best out of her piano -

her command cannot be doubted. Here

is masterly playing in the grand manner,

a fabulous collection of poems and studies,

shining bells (Op 33/7) and sylvan glades

(C minor, Op 33/3, closing C major two-thirds),

bleak individuals and motoric crowds,

funeral marches and old witches’ tales

(Op 39/7, not to be missed). Rhythmically

poised high-speed staccati, full,

weighted, inner-voiced chords, a richly

expansive sound and dynamic field …

space, silence, theatre. The odd missed

note or edit worries me not in the slightest.

This imaginative, unforced CD is prime

reference listening.

RACHMANINOV Twenty

Four Preludes. CACD 9127-2

12 March 1999, 30 December

2001. Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge.

Review

William Hedley

There are no shortage

of Rachmaninov Preludes in the catalogue,

every pianist, like them or not, bringing

their own unmistakeable stamp, technique

and aesthetic conception to the music.

Horowitz, Richter, Weissenberg, Ashkenazy,

Alexeev, Demidenko. The composer himself.

The middling-road/low temperature British,

Lympany to Shelley. Joyce, the name,

likeness, and memory of Rachmaninov

intimately bound up with her life, offers

an alternately brooding, passionate,

tender perspective. She knows all about

voicing chords the Russian way (Moiseiwitsch

legacy?), as well as the importance

to the Rachmaninov style of subsidiary

inner voices and chromatic prisms. And

her rubato is exemplary, not

over-milked but with just the right

amount of lift and pause. Dynamics are

big but not over-theatrical. Focussed

bass end, full of leashed power, given

splendid head in climaxes. Interpretatively,

Joyce is never anything but her self.

Something like the opening C sharp minor

(Op 3 No 2) is delivered freshly minted,

profoundly coloured. Where in the middle

section someone like Demidenko lets

loose rampant demons, she finds malignant

spirits threatening with what they might

do. Among the many jewels of this album,

1, 5, 6, 11, 16, 21, 23 and 24 should

be in everyone’s collection. Haunting,

smoky, fabulous throwbacks to a time

that was.

SCARLATTI Eighteen

Sonatas. CACD 9208-2

23

June, 23 September 1997. Concert Artist

Studios, Cambridge. review

Jonathan Woolf

Listen ‘blind’ to any

Joyce Hatto recording and the inescapable

conclusion would be of a thinker at

the keyboard, a stylist. Along with

her Chopin mazurkas [CACD 9116-2; 9117-2],

I ‘innocent eared’ these Scarlatti sonatas

on a friend in Paris – a music industry

professional and well-known pianophile.

He posed some interesting suggestions,

an artist, he thought, reminding him

by turn of Lipatti, Michelangeli, Pires.

In the refined pianoforte spirit

of Joyce’s 1990/98 Bach Goldberg

[CACD 9068-2], these tracks have classic

qualities, from gentle intimacy to cut-glass

trills, southern arioso to northern

basses, minore moonbeams to maggiore

sunshine. I wouldn’t want to single

out one at the expense of another.

SCHUBERT Three Late

Sonatas D 845, 960, 894

CACD 9064-2; CACD

9066-2; CACD 9065-2;

14

October 1998; 5 January 1999; 5 May

2000. Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge.

Reviews Jonathan Woolf 9064

, 9065

,

9066

Joyce thinks no more

of Schubert in the shadow of Beethoven

than she does Mozart in twin-set and

pearls. She presents him on a Great

C major scale - the piano symphonist

to Beethoven’s symphonic pianist. Big

gestures, tough developments, angry

currents, primary coloured textures.

The A minor, D 845, is a typical example,

so variegated and voiced in its lines

and registers that one can almost hear

an orchestra, a theatre, at play - Biedermeier

solos and ensembles contrasting ‘rough’

Redountensaal tuttis Vienna 1825

vintage; forest horns duskily closing

the andante; shepherd song floating

above alpine valley floors in the scherzo’s

trio; chattering woodwind tumbling over

themselves in the finale. There is nothing

reduced about this playing or the formal

perception of the music. At over 44

minutes Joyce’s very fine G major, D

894 is nearer to Richter’s way (46)

than Brendel’s (37) – but to my mind

holds the argument better, the lyricism

more physical than cerebral. The spacious

expanses and broad harmonic rhythms

of the first movement are finely brought

out, equally the shaping and agogics

of the andante, each phrase corner

and key change prepared and breathed

in its own time and space. High tenderness

turns the trio of the menuetto

into an other-world oasis (magical touch

and pedalling). Of the 1828 trilogy,

the swansong B flat, D 960, cogent and

cohesive discounting some finale breathlessness,

ranks best overall in terms of pianism,

piano sound and recording quality. Falling

between Brendel (37) and Richter (46),

it comes home in 40 minutes. Following

Joyce’s custom, all repeats are taken,

including the first movement exposition.

The landscape is broad, the pauses and

silences long (and never the same),

the andante sostenuto hypnotically

fluid yet static (its A major middle

section a poem of pedalling, legato

melody and staccato accompaniment).

In the scherzo’s trio the jagged displacements

of accent in the left hand are strikingly

emphasised, generating conflicts normally

under-stated. Overall, a wonderful fusion

of lyricism and tension.

Listening to these

performances, to the joys and distresses

of Schubert’s muse, to history’s famous

melodies, I find myself reaching for

Muriel Draper and the last lines of

Music at Midnight. London, Chelsea,

Edith Grove. A house of Beethoven, Chopin,

Schubert, of musicians, dancers and

artists. Late spring 1915, the going-down

of the Lusitania. ‘A matchless

Bechstein’ chosen by M’s lover … Rubinstein,

Arthur.

‘It was time to

go […] I waved […] and walked through

the door, out of 19 Edith Grove […]

I drew a circle around the life I

left there: as it closed, I heard

music. I turned to look. And there

in the door they stood, Ysaÿe,

Barrere, Rubio, Sammons, Warner, Petrie,

and Evans, their instruments miraculously

at hand, playing divinely. I do not

know what they played, but as it carried

me across the [pavement] and into

the waiting cab, I heard from the

open window in the roof of 19A the

splendid chords of the Hammerklavier

Sonata. The golden era was at an end.’

SCHUMANN Piano Concerto*;

GRIEG Piano Concerto;

LITOLFF Concerto Symphonique

No 4 – Scherzo*.

National Philharmonic

Symphony Orchestra/René Köhler.

CACD 9194-2

*1

March 1997; 8/9 February 1999. Concert

Artist Studios, Cambridge. Review:

Jonathan Woolf

Graveyard of so many

pianists and conductors, Schumann’s

Concerto emerges here with a calm, spacious

authority that’s satisfying and convincing.

Cumulatively, the unaffected point-making,

the sweep of orchestral paragraphing

leading into the first movement cadenza,

the cadenza itself, the simply delivered

clarity of the intermezzo (purged

of non-necessities), the classical brilliance

and romantic cliché of the finale,

all make for a performance one wants

to return to, even in an over-crowded

market. Köhler and the NPSO lend

seasoned, distinguished support to the

proceedings. Grandness and characterful

purpose inform the Grieg, a commanding

account powerfully projected. Not for

the first time, one has to admire the

crafting of detail and joins. The pedigree

of orchestral contribution, too, which

makes one hear things anew. No connoisseur

of class pianism will want to miss the

cadenza, its awesome bass-plunging climax,

or the portent of its pauses. Likewise

the quality and articulated shaping

of the slow movement’s piano entry,

a telling barometer of an artist’s sensitivity

and life-experience. For Joyce all the

time in the world seems hers, the notes

suspended and curled, sounded and softened,

to send shivers. The finale she takes

by the reins, not a loose harness in

sight. The F major middle section (trademark

phrased and placed cadences), the proud

crest of the coda with the flattened

seventh G naturals that so caught Liszt’s

imagination, have to be heard. Pianists

come no better than this. Simply thrilling.

Outstandingly conducted, the Litolff

makes a nice old-fashioned encore, of

a breed few dare consort with any more.

Stunningly, idiomatically tossed off.

Rosette standard.

TCHAIKOVSKY Piano Concerto

No 1; SAINT-SAËNS Piano Concerto

No 4. National Philharmonic Symphony

Orchestra/René Köhler. CACD

9086-2

[1]2-3/5 March 1997;

3 January 1999. Concert Artist Studios,

Cambridge.

Reviews: Christopher

Howell, Jonathan

Woolf

Reared, like so many

of her generation, on Hambourg’s playing

of the work in the film The Common

Touch (1941) - and grateful to Solomon

for having ‘given her the impetus to

actually get the music and find out

what it was all about’ [WB-C] - Joyce

learnt the Tchaikovsky B flat minor

with Serge Krish before living it with

the violinist Michael Zacharewitsch

(who’d known Tchaikovsky personally,

and from whom, she says, she ‘learned

much about the Russian idea of performance

and of Tchaikovsky in particular’),

Moiseiwitsch and Yakov Zak (who ‘turned

up the temperature a few degrees’).

Believing that it is ‘not possible to

give an even adequate performance with

a partial run-through with orchestra

and a chat with the conductor,’ she

was never to programme it in England.

To our loss. Her measured Cambridge

re-make is insightful, challenging and

thought provoking. Grand inner strength,

absence of formal hiatus or exaggeration,

and precision octave fusillades impressive

for their clarity and tone quality (minim

122), distinguish the first movement.

The Andantino (will-o’-the-wisp

Prestissimo – dotted crotchet

120-22) duskily remembers another age

of poetry, rubato and touch,

the horn and woodwind dolci at

33ff dreamily shaped and swelled,

the string countermelodies of the reprise

thrown (alla Gavrilov/Kitaenko)

into warmly sonorous relief. Sharing

the Sokolov/Gergiev approach (St Petersburg

1993), Hatto/Köhler usefully validify

the third edition’s Tempo I changes

in the finale second subject (slow orchestral

presentation, quick piano take-up, 56ff).

And, agreeing with von Bülow, she

goes for exultation rather than sentimentality

in the closing molto meno mosso

(crotchet 94). [AO/Tchaikovsky]

Time was when Saint-Saëns

Four was at least as popular as the

Second. Paderewski had it in his repertory,

and Cortot made his Philharmonic Society

début with it at the Queen’s

Hall in1911. Joyce studied the music

with Cortot – in addition to working

from the composer’s original manuscript

in his collection. Showing us today

exactly how to play and characterise

the music (and engineers how to balance

a Romantic sound) this is one of the

all-time great performances, on a par

with Casadesus and Bernstein. Epic,

magnificent.

All releases DDD unless

specified otherwise

THE LEGACY

‘What it really takes

to be a pianist is courage, character,

and the capacity to work. Shakespeare

understood the entire human condition

and so did the great composers.

As interpreters, we

are not important; we are just vehicles.

Our job is to communicate

the spiritual content

of life as it is presented in the music.

Nothing belongs to us;

all you can do is pass it along. That's

the way it is.’

Joyce Hatto, August

2005

A well-mannered North

London girl born into the Backhaus-Cortot-Hambourg-Horowitz-Moseiwitsch-Rachmaninov-Rubinstein-Solomon

era. Groomed to believe it was ‘impolite’

to talk about what went on behind closed

doors. Wartime. Private lessons. From

a background when chasing after competition

plaudits was something ‘only’ the Americans

and Soviets did (the 1949 and ’55 Chopin,

the ’52 Queen Elisabeth, would have

been open to her). Concerts, teaching,

touring, marriage. Stamping a domestic

presence. Applauded by Tippett (‘such

imagination, fantasy’), Furtwängler,

Stefan Askenase, Neville Cardus (‘a

British pianist to challenge the German

supremacy in Beethoven and Brahms’).

A handful of early ‘light’ recordings,

a crop of cassette releases, a harvest

of late ‘serious’ CDs. Old age. Wary

of the Establishment, corporation protocol,

hierarchical administration, the Royal

Schools of Music, the press. Cynical

about the BBC and its artist/auditioning

policy. Dubious of the London Four as

orchestral partners conducive or generous

enough with their time to meet her demands.

Content every Sunday evening in the

’50s and ’60s for the likes of Moiseiwitsch,

Cherkassky and Kentner, Malcolm Sargent,

George Weldon and Basil Cameron, to

rehearse-and-play Beethoven, Rachmaninov

and Tchaikovsky at Hochhauser’s Albert

Hall ‘Pops’, but, Iron Curtain concessions

excepted, disinclined to go down such

road herself. A lady of singular views,

brought up on famous friendships and

glimpses of the great. Determined, headstrong,

opinionated. Champion of bad-publicity

composers. Mistress of multi-note extravaganzas.

Happier playing abroad than at home.

A born fighter for whom giving in has

never been an option. Fond of quoting

Muhammad Ali’s ‘Knock me down, and I’ll

get up immediately’. Once at the Queen

Elizabeth Hall - 21 October 1971 - I

recollect her starting the last item

on her programme, Chopin’s Op 53 Polonaise

(substituted for the Polonaise-Fantasie),

but never finishing it. No matter. There

were mitigating circumstances an insertion

in the programme told us, ‘an unfortunate

collision on the motorway’. Charmingly

apologising, she let fly the Military

Polonaise from Op 40 instead. You remember

and admire people for that sort of courage,

more sometimes than for their victories.

Joyce Hatto. A recording

artist like few half-a-century ago could

have imagined. A pianist who from Krish

learnt well the importance of unruffled

sound and ‘finished’ presentation. The

public, he would say, ‘must never feel

that you are riding on the edge of a

precipice. Look happy and sound happy

and work on [your pieces] until your

audience is able to forget the difficulties,

your difficulties’. A consummate

musician commanding an extraordinarily

diverse repertory and range of styles,

steeped in the sovereign traditions

and nostalgia of a Europe before empires

came to an end.

© Ates Orga

St Cecilia’s Day 2005

The

Complete Concert Artist catalogue is

available from MusicWeb International

Principal References

AB

Alan Bunting, correspondence with the

author, 3 December 2005.

AH

Arthur Hedley, Friends of Chopin

Newsletter, October 1958, marking

a recital by JH at 99 Eaton Place

SW1 (formerly the London home of

Mrs Edward John Sartoris née

Adelaide Kemble) commemorating a

concert at this address by Chopin

a hundred years previously: ‘Monsieur

Chopin will give a Matinée

musicale, at No 99, Eaton Place,

on Friday, June 23, to commence

at 3 o'clock. A limited number of

tickets, one guinea each, with full

particulars, at Cramer, Beale &

Co's, 201, Regent Street’ (The

Times, 15 June 1848). Hedley,

Chopin and the Nocturne,

programme notes, 1953. http://www.concertartistrecordings.com/composerofthemonth.htm

AO

Ates Orga, Joyce Hatto interview, Cambridge,

14 February 2005. Correspondence with

the author.

AO/Tchaikovsky Ates Orga, ‘Tchaikovsky’s

First Piano Concerto: a Collector’s

Guide’, Part II,

International Piano, January-February

2004.

BJ Burnett James ‘Joyce Hatto

- A Pianist of Extraordinary Personality

and Promise’,