|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

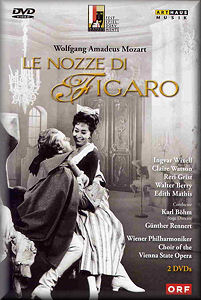

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791)

Le Nozze Di Figaro - Opera buffa in four acts

(1786)

Susanna,

maid to the Countess – Reri Grist (soprano); Figaro, manservant to

the Count - Walter Berry (bass-baritone); Count Almaviva - Ingvar

Wixell (baritone); Countess Almaviva - Claire Watson (soprano); Cherubino,

a young buck around the palace – Edith Mathis (soprano); Marcellina,

a mature lady owed a debt by Figaro – Margarethe Bence (mezzo); Don

Basilio, a music master and schemer – David Thaw (tenor); Don Bartolo

- Zoltan Keleman (bass); Barbarina - Deirdre Aselford (soprano). Susanna,

maid to the Countess – Reri Grist (soprano); Figaro, manservant to

the Count - Walter Berry (bass-baritone); Count Almaviva - Ingvar

Wixell (baritone); Countess Almaviva - Claire Watson (soprano); Cherubino,

a young buck around the palace – Edith Mathis (soprano); Marcellina,

a mature lady owed a debt by Figaro – Margarethe Bence (mezzo); Don

Basilio, a music master and schemer – David Thaw (tenor); Don Bartolo

- Zoltan Keleman (bass); Barbarina - Deirdre Aselford (soprano).

Chorus of the Vienna State Opera

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Karl Böhm

rec. live, Salzburg Festival, 1966

Stage direction - Günther Rennert

Set and Costume Design - Ludwig Heinrich

Video Director - Herman Lanske

Sound Format: PCM Mono, DD 5.1. Picture Format: 4:3. DVD Format NTSC

2 x DVD 9

Subtitle Languages: Italian (original language), English, German,

French, Spanish, Chinese

ARTHAUS MUSIK

ARTHAUS MUSIK  107 057 [2 DVDs: 180:00]

107 057 [2 DVDs: 180:00] |

|

|

Mozart’s Le Nozze Di Figaro is widely regarded as among

the greatest operas ever penned. Designated opera buffa,

it is based on the second of Beaumarchais’s trilogy of plays

set around Count Almaviva. It is a superb marriage of composer

and librettist, in this case Lorenzo Da Ponte, a man surely

unique in the annals of music. Propitiously, he arrived in Vienna

at the turn of 1781-82. This was a year before the Emperor restored

Italian Opera to the Imperial Theatre, the Burgtheater. He was

appointed Poet to the Imperial Theatres by the Emperor

and thus had easy access to his august and all powerful employer.

In relatively liberal Paris, Beaumarchais’s play was, for many

years, considered too licentious and socially revolutionary

for the stage. It was viewed similarly in Vienna even after

the more liberal Emperor Joseph II had come to power on the

death of his mother. Da Ponte, used his access to the Emperor

and managed to get his permission for Mozart’s Le nozze di

Figaro to go ahead on the basis of it being

an opera and not the already banned play. This necessitated

the more political and revolutionary aspects of the play being

toned down. This had consequences for an inflammatory Act 5

monologue which was replaced with Figaro’s Act 4 warning about

women which greatly pleased the Emperor. Mozart composed the

music in six weeks despite a flare-up of the kidney condition

that was to kill him five years later at the very young age

of thirty-five.

Opera festivals abound in what might be called the closed season

for the great theatre addresses for the genre. None come bigger,

or more expensive, than the Salzburg Festival that runs for

five weeks from the end of July each year with an earlier Whitsun

or Easter offspring. Salzburg was the birthplace of Mozart and

since the inception of the Festival, around 1920 by Richard

Strauss, his librettist Hofmannsthal and Max Reinhardt, the

great native composer’s operatic works have never been less

than a regular feature. None of those operatic works has clocked

up more productions and performances than Le Nozze Di Figaro.

The Festival and the work tempt the most prestigious producers

and conductors. Famous conductors associated with the Festival

include Toscanini, Bruno Walter and Karajan. Karl Böhm stands

alongside these giants with a claim to having a particular empathy

with Mozart’s music. Certainly his Le nozze di Figaro

and Cosi fan Tutte at Salzburg are renowned. Böhm’s conducting,

alongside Günther Rennert’s production, Ludwig Heinrich sets

and opulent costumes as presented in this film, even in the

limitations of mono sound and black and white presentation,

show why that is so.

In 1966, as now, the Salzburg Festival drew the cream of singers,

and this cast includes some of the all time great Mozart interpreters.

In no order, Reri Grist’s Susanna, petite and pert in manner,

true in vocal characterisation and excellent in diction, is

a particular delight. Her act four recit and aria is a wonderful

postlude to an outstanding contribution (DVD 2 CH. 27). As her

eponymous paramour, Walter Berry is quite some revolutionary.

It would take a very strong count Almaviva to master him. His

singing is full-toned with his rounded bass baritone flexible

and expressive in Figaro’s arias (e.g. DVD 1 CH.6 and 17). His

acting is convincing. This is particularly so in the concluding

act in the garden (DVD 2 CHs.18031) where the various confusions

bring Figaro and his bride and the put-upon Countess full justification

for the plotting that has gone before.

Of the Almavivas and their entourage, Claire Watson’s warm-toned

and womanly Countess comes over well. She finds no difficulty

with the tessitura of her two big arias whilst bringing expression

and feeling to the emotions they convey (DVD 1 CH.18 and DVD

2 CH.10). Ingvar Wixell sings strongly as the Count, albeit

overshadowed a little by his servant in terms of vocal strength.

That lovely Mozartian Edith Mathis, as the young buck Cherubino,

looks a little too feminine of face. She sings her two arias

with great beauty and acts the role convincingly, particularly

after entering Susanna’s room via a window (DVD 1 CH 11-17)

and then having to hide herself as the Count arrives. She graces

both arias with tonal beauty and phrasing too rarely heard these

days. Zoltan Keleman is a rather cocky Don Bartolo, but sings

his aria adequately (DVD 1 CH.8). Margarethe Bence is a rather

fusty-looking Marcellina and like David Thaw’s adequately acted

music-master she does not get their act four aria. Deirdre Aselford

is vocally a little thin as Barbarina but acts her role well,

especially in act four.

Ludwig Heinrich’s classic sets and costumes made me regret the

lack of colour. Karl Böhm’s phrasing and gently sprung rhythms

allow the composer’s music to flow whilst giving the singers

adequate time to phrase with delicacy and character. A little

matter of changing styles is evidenced in the return of a singer

to the stage after exiting at the end of an aria, to take a

bow, or even two. Thankfully this practise has now died out

with soloists criticised for even showing the hint of a smile

as they maintain role during the enthusiastic reception following

a bravura aria. All one would wish nowadays is for audiences

to follow suit and restrict their applause to the end of acts

and at final curtain.

Robert J Farr

|

|