|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

Johannes BRAHMS

(1833-1897)

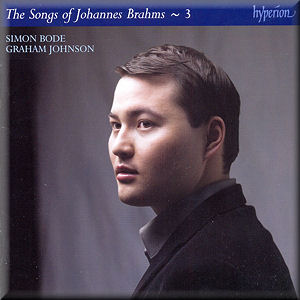

The Songs of Johannes Brahms - 3

Wach auf, mein Herzensschöne Wo033/16 [2:08]

Erlaube mir, feins Mädchen Wo033/2 [1:22]

Mein Mädel hat einen Rosenmund Wo033/25 [2:01]

Ein Sonett op.14/4 [1:54]

Ständchen op.14/7 [3:18]

Der Kuss op.19/1 [1:51]

An eine Äolsharfe op.19/5 [4:03]

Magyarisch op.46/2 [2:54]

Die Schale der Vergessenheit op.46/3 [1:43]

Fünf Lieder op.49 [12:37]

Mein wundes Herz verlangt op.59/7 [1:54]

Im Garten am Seegestade op.70/1 [2:23]

Lerchengesang op.70/2 [2:51]

Serenade op.70/3 [1:21]

An den Mond op.71/2 [3:17]

In Waldeseinsamkeit op.85/6 [2:35]

Auf dem Schiffe op.97/2 [1:07]

Es hing der Reif op.106/3 [2:52]

Ein Wanderer op.106/5 [3:02]

Die Sonne scheint nicht mehr Wo033/5, Wo gehst du hin, du Stolze?

Wo033/22 [1:18]

Es steht ein Lind Wo033/41 [2:45]

Simon Bode (tenor), Graham Johnson (piano)

Simon Bode (tenor), Graham Johnson (piano)

rec. 23-25 November 2009, All Saints’, Durham Road, East Finchley,

London

Original texts included with English translations

HYPERION CDJ33123 [60:51]

HYPERION CDJ33123 [60:51]

|

|

|

This is the third volume of the Brahms song edition masterminded

by Graham Johnson. He explains in some detail, and even a little

defiantly, his reasons for not arranging the project chronologically

or by opus number. Here is just one significant passage:

There is a modern tendency to see a famous cycle like

Winterreise as the nineteenth-century norm to which all other

groups of songs should be made to conform, and this ‘search

for cycles’ has become something of an obsession in present-day

musicology, a means of using the popularity of Schubert’s

and Schumann’s genuine cycles as an excuse to pretend

that there are similarly cohesive works in the repertoire waiting

to be rescued, or restored to the unified shape the composer

had intended for them all along. It is perhaps a symptom of

our ‘bigger is better’ society that solitary songs,

exquisite miniatures, are thought to be more significant if

they form part of something bigger. If this is true, it represents

an ongoing challenge to the planners of programmes whose efforts

can yield far better and more imaginative results when allowed

to range over a broader canvas than that of a single opus where

all sorts of practical considerations, including commercial

ones, had restricted the composer’s choices.

This is all music to my ears, since I have always been inclined

to think that the modern tendency of doing things rigorously

by the opus-full, or chronologically, is in a way an abdication

of the responsibility earlier performers felt they had towards

their audiences. You have to be careful if you’re not

Graham Johnson. The planning of this Brahms series will doubtless

be universally acclaimed - not least by me - as yet more proof

of Johnson’s brilliant and masterly approach to programme-planning.

I’ve found, to my cost, that if I spend sleepless nights

devising what I hope is a listener-friendly sequence of a selection

from an area of a composer’s work, rather than sticking

to opus-number sequence and numerical order within the opuses,

I just get accused of making a random selection. I admit, though,

that in a complete edition it is easier to find a particular

song if it’s all laid out encyclopaedically. If you want

your Brahms done that way, it’s already there on CPO,

with such fine singers as Andreas Schmidt and Juliane Banse

accompanied by Helmut Deutsch, maybe a less probing artist than

Johnson but a splendid purveyor of received-opinion Brahms.

Received-opinion Brahms isn’t quite what you get here,

but since I realized this gradually, let me come to it gradually.

Johnson lays stress on the importance of folksong arrangements

in Brahms’s output. He points out that, while Brahms came

too early for what we now know as ethno-musicology and happily

took on board tunes that sounded like folksongs but weren’t,

he was nevertheless the only one of the great Lieder composers

to dedicate substantial time and passion to arrangements of

this kind. The largest collection, the 49 Deutsche Volkslieder,

will be spread across the entire project. Here we have three

at the beginning and three at the end. One can only delight

in the transparency of the piano textures and the simplicity,

yet high art, of the singer’s response. It cannot be easy

to sing “Du la la la la la!” differently every time

it comes, and without mannerism, but here it is achieved.

As the original songs begin, there is the same clarity of texture,

the same refinement of the vocal line. Gone, for the better

I thought at first, was the thick-textured Brahms we used to

know. Johnson’s analysis of the vocal problems Brahms

creates in “Der Kuss” - as ever, he provides a minutely

detailed commentary on each song - almost seems designed to

induce the reaction that it sounds easy enough as sung here.

I’m not quite sure just at what point I began to wonder

if I was getting the full story. Maybe “Die Schale der

Vergeissenheit” was the moment, for the climax is placed

fairly high in the voice, and forte. Something in sheer fullness

seemed to be missing from both artists.

Having begun to think that way, the thought came more and more

often. Simon Bode has an unquestionably beautiful voice, his

line is exquisitely controlled and his care over words and meaning

were already evident in the folksong settings. One of his specialities

seems to be high notes that are gently floated, honeyed, with

the help of a generous dose of falsetto. When forte high notes

come, it has to be said that the voice is inherently a little

small. He resolves the situation by maintaining the same refinement,

still with a spot of falsetto. Better this, clearly, than strident,

forced tones. Given the resources he has, his husbanding of

them is admirable. In most Schubert and a lot of Schumann, maybe

the point wouldn’t have crossed my mind. I daresay I’ve

been living in Italy too long, but in the fullness of a Brahmsian

climax I longed for more sheer, even brainless, singing.

Did Johnson choose Bode as the ideal singer to give him the

Brahms he wanted? In the piano parts, too, I began to suspect

an excess of refinement. Take “Sehnsucht”. The bass

crotchets are marked staccato, but are also grouped in threes

with a legato line. The triplet quavers, harmonic rather than

melodic, are also marked with slurs. Did Brahms literally want

a dry, unpedalled staccato, or are the staccatos intended as

touched, to be taken in conjunction with a careful pedalling

to give warmth to the harmonies outlined by the triplets. Alexander

Schmalcz, accompanying Stephan Loges (Athene 23202) thinks the

latter. This is Brahms as we traditionally understand him, warm

and not at all muddled. Johnson thinks the former. The bleakness

seems closer to Hindemith than to Brahms.

Then, in the same op.49 group, should not the repeated bass-notes

of “Abenddämmerung” resonate with a funereal

quality, something like the beginning of the “Deutsches

Requiem”? What to think of “Im Garten am Seegestade”,

where the staccato - but also slurred - quavers are taken as

an invitation to seek a two-part invention in what is surely

meant as an evocation of the waves lapping on the shore. Don’t

get the idea that this is all dry and unpedalled, there are

many occasions, such as a little later in this same song, where

Johnson uses tiny little dashes of pedal to create textures

of almost impressionist refinement. Brahms isn’t Ravel

and in the moments I have described this seems to me not so

much Brahms as anti-Brahms. Does not Brahms call for a broader

brush? Even the detailed commentaries, full of perception as

they are, sometimes read like an insistence on little points

that, while true, should be just “there”. One thing

Brahms won’t take is fussiness, and in certain moments

Johnson seems to fuss over his Brahms like an old woman at her

embroidery.

There are marvellous things, such as a wondrously sustained

“Es hing der Reif”. Indeed, according to their own

lights, all the performances are marvellous. Put it another

way. Every Brahmsian quality you could want is here except fullness

of heart, free-flowing generosity of spirit. If these are the

qualities you most value in Brahms, you might have some problems.

If, on the other hand, you’ve never taken to the blue-eyed

old sentimentalist, with his swings between schmaltz and grumpiness,

you may be in for a revelation.

Christopher Howell

|

|