|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

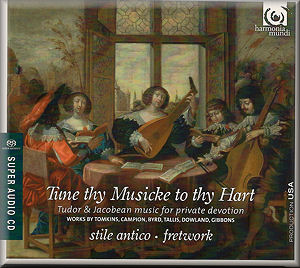

Tune thy Musicke to thy Hart - Tudor

and Jacobean music for private devotion

Thomas TOMKINS (1572-1656)

O praise the Lord [3:45]

John AMNER (d.1641)

O ye little flock [7:06]

John TAVERNER (c.1490-1545)

In nomine (Missa Gloria tibi Trinitas) [2:04]

Robert RAMSEY (1590-1644)

How are the mighty fall’n [6:30]

Thomas TALLIS (1505-1585)

Purge me, O Lord [1:52]

John AMNER

A stranger here [5:04]

Robert PARSONS (c. 1530-1570)

In nomine a 4 No 1 [2:36]

John BROWNE (fl. 1480-1505)

Jesu, mercy, how may this be? [10:04]

Robert PARSONS

In nomine a 4 No 2 [2:19]

Giovanni CROCE (c. 1557-1609)

From profound centre of my heart [4:37]

John DOWLAND (1562/63-1626)

I shame at my unworthiness [2:21]

Thomas CAMPION (c. 1567-1619)

Never weather-beaten sail [2:39]

William BYRD (c. 1540-1623)

Why do I use my paper, ink and pen? [2:30]

Thomas TOMKINS

When David heard [5:03]

Orlando GIBBONS (1583-1625)

See, see, the Word is incarnate [6:19]

Stile Antico/Fretwork

Stile Antico/Fretwork

rec. Air Studios, Lyndhurst Hall, London, February 2011. DSD

English texts, French and German translations included

HARMONIA MUNDI HMU 807554 [64:45]

HARMONIA MUNDI HMU 807554 [64:45]

|

|

|

Several of the vocal works on this programme – Amner’s O

ye little flock and When David heard

by Tomkins, for example – have been in the repertoire of church

choirs for a long time. However, Matthew O’Donovan contends

in his very interesting booklet note that the music presented

here was written for domestic use rather than to be heard during

church services. He maintains that there was a significant amount

of domestic music-making in sixteenth-century England and that

religious music of the kind performed here was frequently used

in the context of private or domestic devotion. And it’s clear

that we’re not just talking about aristocratic households in

this context but also music-making among the middle classes.

O’Donovan’s argument is persuasive and obviously well researched.

The only point I’d make, while not challenging his thesis for

a second, is that a good deal of the music we hear in this recital

would have required some pretty expert executants.

One such example is John Browne’s Jesu, mercy, how may this

be? which may well be the earliest music on the programme.

As Matthew O’Donovan says, there’s certainly a directness of

communication about this piece, not least in the fourth of the

five stanzas, which is relatively dramatic – at least as Stile

Antico render it. What is noticeable, however, is the quite

florid style of writing which involves quite a lot of ornamentation

of the vocal lines. This music seems much closer to the world

of the Eton Choirbook than to private chapels and the domestic

environment. The members of Stile Antico give a very fine performance

of it, one that is all the more remarkable when one remembers

that this group performs without a conductor.

In complete contrast the little piece by Tallis shows him at

his most simple and direct. Campion’s Never weather-beaten

sail, a setting of his own words – set memorably by Parry

some three centuries later as one of his Songs of Farewell

– is also musically fairly straightforward, owing much, as O’Donovan

observes, to metrical psalmody. It’s interesting that in this

piece the words are rather richer in expression than the music.

In general the pieces are quite modest in scale but this doesn’t

necessarily mean that they’re musically modest. Robert Ramsey,

in his How are the mighty fall’n, and Thomas Tomkins,

in When David heard, both choose words from the Second

Book of Samuel. Ramsey’s piece gives expression to a patrician

grief and his short anthem is full of feeling. So too is the

Tomkins piece, perhaps the best-known music on the disc, which

conveys an abundance of dignified but deep feeling. The performances

of both pieces are beautifully judged and I found it was very

rewarding to fast-forward the CD and hear one after the other.

John Amner’s delightful little verse anthem for Christmas, O

ye little flock is another example of direct musical communication.

The music exudes a beguiling innocence – certainly that’s the

case in this performance. Rather more elaborate is See,

see, the Word is incarnate by Gibbons but even here the

composer connects directly through what is basically simple

expression. Musical artifice is not allowed to impede devotion,

rather the music is consciously fashioned so as to aid

devotion, which is not to imply that the music is unsophisticated.

In these two pieces Stile Antico are joined by the viol consort,

Fretwork. The viols also accompany tenor Benedict Hymas in the

one solo vocal item, Byrd’s Why do I use my paper,

ink and pen? which he sings very well. Fretwork also

perform by themselves in the three In nomines.

Collectors who have acquired previous releases by Stile Antico

won’t be at all surprised to learn that the standard of performance

is extremely high. The homogeneity and blend of the group is

flawless and solos or duets – in the Gibbons, particularly –

are all well taken. Fretwork, of course, is well known as one

of the premier viol ensembles and their contribution to the

success of the disc is equally significant. Incidentally, followers

of Fretwork may wish to know that this was the very last recording

made with them by one of their founder members, Richard Campbell,

just a matter of weeks before his untimely death last year.

This beautifully packaged and carefully documented release offers

a most interesting perspective on the sacred vocal music of

the period and exemplary performances. The recordings, which

I listened to as a conventional CD, are clear and present with

just the right amount of ambience around the musicians.

John Quinn

|

|