|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

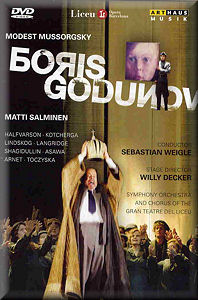

Modest MUSSORGSKY (1839-1881)

Boris Godunov - opera in seven scenes (original 1869 version)

Boris Godunov, Tsar of Russia - Matti Salminen (bass); Fyodor, his son - Brian Asawa (counter-tenor); Xenia, his daughter - Marie Arnet (soprano); Xenia's Nurse - Stefania Toczyska (mezzo); Prince Vassily Ivanovich Shuisky, a Boyar - Philip Langridge (tenor); Andrei Schelkalov, secretary of the Boyars - Albert Shagidullin (bass); Pimen, a monk - Eric Halfvarson (bass); Grigory, the false Dimitri, - Pär Lindskog (tenor); Varlaam, a roistering friar - Anatoly Kocherga (bass); Missail, his companion - José Manuel Zapata (tenor); A Simpleton - Alex Grigoriev (tenor)

Boris Godunov, Tsar of Russia - Matti Salminen (bass); Fyodor, his son - Brian Asawa (counter-tenor); Xenia, his daughter - Marie Arnet (soprano); Xenia's Nurse - Stefania Toczyska (mezzo); Prince Vassily Ivanovich Shuisky, a Boyar - Philip Langridge (tenor); Andrei Schelkalov, secretary of the Boyars - Albert Shagidullin (bass); Pimen, a monk - Eric Halfvarson (bass); Grigory, the false Dimitri, - Pär Lindskog (tenor); Varlaam, a roistering friar - Anatoly Kocherga (bass); Missail, his companion - José Manuel Zapata (tenor); A Simpleton - Alex Grigoriev (tenor)

Cor de Cambra del Palau de la Musica Catalana

Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona/Sebastien Weigle

rec. live, Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona, 2004

Stage Director: Willy Decker

Set and Costume Designer: John McFarlane

Revival Director: Martin Gregor

TV and Video director: Xavi Bové

Picture format: 19:9 NTSC; Region Code: 0. Sound format: PCM Stereo, DD 5.1.

Subtitles in English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Catalan. Booklet essay: English, German, French, Spanish

ARTHAUS MUSIK 107 237

ARTHAUS MUSIK 107 237  [152:00]

[152:00]

|

|

|

Recognized today as its composer's masterpiece and one of the

most important operas of its genre, Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov

had a difficult birth and a chequered life. The composer created

his own libretto from the historical tragedy of the same name

by Alexander Pushkin's and from Nikolai Karamzin's History

of the Russian State. Its boldly contrasted succession of

scenes, its swift pace and terse declamation, along with its

differentiation of character by musical means ensure a powerful

impact. Many of Mussorgsky's contemporaries found his musical

idiom strange and harsh.

He began the composition of Boris Godunov in October

1868 and carried on until it was finished in its first form

in December 1869. To do so he gave up his Civil Servant job

in St Petersburg, then the Capital of Russia. He was forced

to take a similar job later, perhaps to fund the alcoholism

that helped kill him in a week before his forty-second birthday

in 1881. The Maryinsky Theatre rejected his efforts in 1871,

considering the work lacked the normal components of an opera,

there being no prima donna, love interest, ensembles or dancing

and also, perhaps, in anticipation of trouble with the censors

as the work delved into Russia’s troubled past and the worries

of the people.

Mussorgsky added a prima female role with a love interest in

a remodelled version completed in 1872; the Maryinsky also rejected

this. However, extracts were given in concert in the theatre

and the work accepted for publication. This time it received

its premiere, with some cuts, on 27 January 1874. It was a moderate

success, but after the composer’s death, leaving behind four

other operas uncompleted, it fell from the repertoire. In an

effort to revive interest and return it to the repertoire, his

friend Rimsky-Korsakov re-orchestrated the work altering melody,

harmony, keys, and dynamics making it brighter and smoother

whilst also stating: I have not destroyed its original form,

not painted over the old frescoes for ever. If ever the conclusion

is arrived at that the original is better, then mine will be

discarded and Boris Godunov will be performed according to the

original score. The Rimsky-Korsakov version was

premiered in 1896 and with further modification in 1908. This

held sway under the influence of Chaliapin, Christoff (see review)

and Ghiaurov in the title role all of whom recorded their interpretation

of Boris in this form. I was fortunate to see the latter two

in live performances of the Rimsky version at Covent Garden

before Mussorgsky’s own replaced it in a renowned production

by Tarkovsky shared with the Maryinsky Theatre. Later in the

1960s there was a general, albeit gradual, move back towards

Mussorgsky's original with performances by the Welsh National

Opera among others; the Welsh featuring Forbes Robinson as Boris.

This move was given a further spur by the first recording of

this original version, along with all the 1872 additions and

featuring Martti Talvela in the title role (EMI 7 54377 2).

Many major opera houses now follow this practice. This particular

production originated at the Nederlandse Opera, Amsterdam. It

includes some additions from Mussorgsky’s second version of

1873 but does not include the major love interest of the Polish

scene.

The events of the opera take place in Moscow and elsewhere between

1598 and 1605. They fall within what Russian historians call

The Times of the Troubles between the death of Ivan (The

Terrible) in 1584 and the establishment of the Romanov dynasty.

In 1584 Fyodor, a son by Ivan’s first wife succeeded him whilst

her brother, Boris Godunov, established himself as the power

behind the weak young king who died. Another young son by Ivan’s

last wife, his seventh, named Dimitri was sent away to a Monastery

in 1591 where he died in mysterious circumstances, believed

killed by Boris or on his instructions. A rumour spread that

he had not died but escaped a plot to kill him. This rumour

gave rise to the appearance of a pretender to the throne in

1603, the so-called False Dimitri.

The sets of this production by Willy Decker are minimalist.

Like his Salzburg La Traviata (see review)

major motifs dominate. In this case we have a very large gilded

chair symbolising the throne and power of the Tsar. In the first

scene the chair is on its side. Cradled within it is a child

dressed only in a loin cloth and holding the Tsar’s crown in

his lap. This child is murdered by a group of trench-coated

men. A portrait of his face is Decker’s second dominant motif;

the portrait appearing regularly throughout as the influence

of the murdered true Dimitri is felt, at least as Decker perceives

it. Tall bleak grey walls flank the stage with only the back

opening out as the chorus enter as Russian peasants. This opening

shows the bright interior of the Tsar’s Palace for the clock

and map scene as the young Fyodor shows off his learning to

his father (CHs.24-33). There is no map or recognisable clock,

rather a series of various gilded shapes; at least this provides

some colour. Costumes are uniformly updated to the present

with the populace and soldiers in grey garb. The Boyars are

business-suited and in the final scene enter with rather strange

gilded headgear, perhaps to indicate their status (CHs.37-40).

They, like the patrons of the Inn, bring in and sit on school-type

wooden chairs.

These sparse sets and costumes perhaps illustrate the bleakness

of this episodic story. One is often left cogitating on the

meaning of the symbolism as when the Simpleton appears dressed

only in a loin cloth (CHs.34-37). Is this like the murdered

young Tsar showing naivety and innocence? It certainly thrusts

much greater pressure on the singers to create a character in

their acting and singing. This is particularly true of Philip

Langridge’s masterfully creepy portrayal of Shuisky: smarmy,

fawning and creeping, all conveyed as rarely seen. Both the

singing and acting of Alex Grigoriev’s Simpleton is of a similar

standard in his brief scene (CH.35). That scene ends in the

most effective use of the motifs as the Simpleton pleads to

Boris to slaughter his child tormentors as he did the young

Tsarevich (CH.36). The chair topples, multiple portraits drop

around him and he is left alone on the stage. The bluff lyric

tenor of Pär Lindskog as Grigory is another worthy realisation

with similar quality singing and acting also coming from Marie

Arnet, and particularly Brian Asawa, as Boris’s children. It

is a particular treat to have a male singer as Fyodor, with

Brian Asawa’s acting adding to his vocal strengths. The only

non-bass among the significant remaining roles is Manuel Zapata

who sings uncommonly gracefully as Missail, the second vagabond

friar.

None of the clutch of basses is less than capable and distinguished

in their singing and acted interpretations. As Andrei Schelkalov,

secretary to the Boyars, Albert Shagidullin is a voice new to

me; he is a musical and strong, even-toned singer (CH.4). Eric

Halfvarson, who is often heard as the Inquisitor in Don Carlo

(see review),

is cavernous in tone and acts his role with distinction (CHs.11-16

and 41), whilst Anatoly Kocherga as the roistering Varlaam is

as strong and virile in portrayal as he is in voice (CHs.20-21).

However, at the end of any performance of Boris it is the singer

of the name part who carries the day. In the Coronation Scene

(CHs.7-10) Matti Salminen’s opening phrase was a little unsteady,

but was quickly into full sonorous and characterful voice as,

with Orb, Sceptre and gilded cloak he is crowned and hoisted

onto the large gilded chair, now upright and with a portrait

of the child being ripped from it and cast, symbolically, on

the floor. Salminen’s acting is suitably avuncular in Boris’s

scene with his children (CHs.24-27) when he quickly changes

vocal tone and emphasis as he sends them away when Shuisky arrives

(CH.30) and reaffirms the death of the infant Dimitri. In the

last act, as Boris calls the Boyars and anoints Fyodor before

dying, he is very good indeed in variation of tonal colour,

emphasis and expression. As he clasps his son to him, in open-necked

shirt devoid of the accoutrements of crown and cloak, he portrays

a very vulnerable and human Tsar, whatever Boris may, or may

not have done in his past in the pursuit of power. As Fyodor

is hoisted onto the chair, crown on head, one wonders if he

will be up to Shuisky’s slyness or will he go the way of the

young Dimitri.

This production and performance is, in its minimalist way, a

powerful realisation of Mussorgsky’s first version of Boris

Godonov. Many will find the greyness depressing and no compensation

for the vibrant choral singing or the musical representation

of the score by Sebastien Weigle. They will find a completely

different staging, and more raw idiomatic choral work by native

Russians, in the DVD recording of the complete 1872 version

in Andrei Tarkovsky’s production caught at the Maryinsky in

1990. Conducted by Valery Gergiev it features Robert Lloyd as

a vocally formidable Boris matching all the Russians in their

own language. Its only drawback is that it is in 4:3 format.

Robert J Farr

|

|