|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

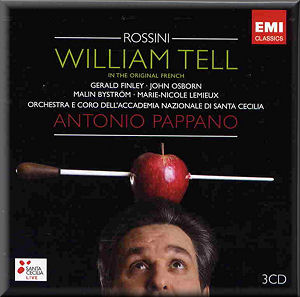

Gioachino ROSSINI (1792-1868)

Guillaume Tell - Opera in four acts (1829).

Guillaume Tell - Gerald Finley (baritone); Arnold - John Osborne

(tenor); Walter Furst - Matthew Rose (bass); Melcthal - Frederic

Caton (tenor); Jemmy, Tell’s son – Elena Xanthoudakis (soprano);

Gesler, Governor of the Cantons of Schwyz and Uri – Carlo Cigni

(bass); Rodolphe - Carlo Bosi (tenor); Mathilde, Princess of the

House of Habsburg – Malin Byström (soprano); Hedwige, Tell’s wife

- Marie-Nicole Lemieux (soprano)

Guillaume Tell - Gerald Finley (baritone); Arnold - John Osborne

(tenor); Walter Furst - Matthew Rose (bass); Melcthal - Frederic

Caton (tenor); Jemmy, Tell’s son – Elena Xanthoudakis (soprano);

Gesler, Governor of the Cantons of Schwyz and Uri – Carlo Cigni

(bass); Rodolphe - Carlo Bosi (tenor); Mathilde, Princess of the

House of Habsburg – Malin Byström (soprano); Hedwige, Tell’s wife

- Marie-Nicole Lemieux (soprano)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Academia di Santa Cecilia, Rome/Antonio

Pappano

rec. live, performances on 18, 20-21 December 2010, Sala Santa Cecilia,

Rome. DDD. Libretto included

EMI CLASSICS 0 28826 2 [3 CDs: 74.16 + 79.26 + 54.33]

EMI CLASSICS 0 28826 2 [3 CDs: 74.16 + 79.26 + 54.33]

|

|

|

In the first years of his compositional life, 1811-1819, Rossini

composed and presented a total of thirty operas. Like Bach,

Haydn and others before him he did re-cycle some music between

these operas. He also made major revisions to several of them

for different theatres, providing happy ending to tragedies

as with Tancredi for example. It was a hectic creative

pace. By comparison Rossini’s last operas were written over

a more leisurely nine years with three of these works being

major revisions, in French, of earlier Italian operas. In 1828,

when he began composing Guillaume Tell, Rossini was 36

years old and following the death of Beethoven he was the world’s

best-known composer. It was to be his 39th and last

opera despite his living until his 76th year. As

Director of the Théâtre Italien, Paris, Rossini had a guaranteed

annuity for life. In addition to this basic financial security

he had earned considerable sums at the 1822 Vienna Rossini Festival

presented by Domenico Barbaja. This impresario had originally

invited the composer to Naples and presented six of his operas

between February and July of that year. On his visit to London

the following year, Rossini himself presented eight of his own

operas and sang duets with the King. His marriage to his long-term

mistress, Isabella Colbran, also brought a considerable dowry

after she inherited property. With good counsel from banker

friends, Rossini had enough money to live in style. Many have

speculated that given his liking for social activities he saw

no reason to continue the strained and hectic life he had perforce

been leading. There was also the question of his mental resilience

and physical state. Certainly his marriage was not successful

and he and Colbran went their separate ways. In the 1830s his

chronic gonorrhoea was a major health problem to him, exacerbated

by frequent, and futile, stringent and painful treatments.

Whilst Rossini had hinted at possible retirement during the

composition of Guillaume Tell the opera shows no signs

of waning musical creativity or capacity and concern for detail.

On the contrary, not only is it by far his longest opera, a

complete performance lasting nearly four hours, it incorporates

significant orchestral innovations and a closer match between

music and libretto than even he had achieved before. It could

be argued that Tell constitutes a massive step in romanticism

unmatched in France or Italy until Verdi’s later works and in

Germany by Wagner thirty years later. The composer took excessive

care over the opera’s libretto, casting and composition. The

work is based on Schiller’s last completed drama of 1804. Rossini’s

first choice of librettist was Eugene Scribe who had provided

the text for his previous opera, Le Comte Ory, but he

preferred other subjects. Rossini then turned to the academic

Victor-Joseph Étienne, librettist of Spontini’s La Vestale,

and who had transformed the libretto of his Naples opera seria

Mose in Egitto (5 March 1818) into the French Moïse

et Pharon premiered at the Paris Opéra on 26 March 1827.

Étienne presented Rossini with a four-act libretto of seven

hundred verses! Appalled, maybe even overwhelmed, Rossini called

on the younger Hippolyte-Louis-Florent Bis who reduced the work

to more manageable proportions and re-wrote the highly praised

second act. Rossini asked Armand Marrast to recast the vital

section at the end of act 2 where the representatives of the

three Cantons assemble and agree to revolt against the tyranny

of Governor Gesler (CD 2 trs15-20). This is a scene that draws

from Rossini some of his most memorable music in an opera of

much melodic and dramatic felicity.

As well as the greater complexity of the orchestration the tessitura

of the role of Arnold gave the scheduled tenor, Nouritt, difficulties

and after the premiere he started to omit the great act four-aria,

Asile héréditaire, and its cabaletta (CD 3 trs12-13).

Soon further reductions and mutilations were inflicted on the

score. Within a year it was presented in three abbreviated acts.

Further insults followed when act 2 only was given as a curtain-raiser

to ballet performances. An often reproduced anecdote relates

how Rossini met the director of the Opéra on the street who

told him they were going to perform act 2 of Tell that

night, to which Rossini was supposed to have replied What

the whole of it?

The opera was first presented in Italian translation at Lucca

in 1831 and the San Carlo in Naples in 1833. On record the Italian

version with Pavarotti and Mirella Freni under Chailly recorded

in 1978 (Decca) has vied with the 1973 EMI recording in French

with Gedda, Bacquier and Caballé under Gardelli’s baton and

which was reissued at mid price earlier in 2011 (see review).

Both recordings are recommendable featuring as they do a full

text and tenors with good upward extensions although in Gedda’s

case on the EMI recording without much grace of phrase. Pavarotti

who later had a disc entitled King of the High Cs, declined

to make his La Scala debut as Arnold, claiming it would ruin

his voice. A tenor friend of James Joyce is quoted as reporting

that the role of Arnold required 456 Gs, 93 A flats, 54 B flats,

15 Bs, 19Cs and 2 C sharps (The Bel Canto Operas. Charles Osborne.

Methuen 1994 p.132). I cannot vouch for the accuracy of that

estimate, and certainly not in this slightly abbreviated performance

of the Critical Edition score by M Elizabeth C. Bartlett, but

certainly the role demands an ability to rise up the stave with

full tone and dramatic intensity on a regular basis. The Italian

lyric tenor Giuseppe Sabbatini sings the role in the Orfeo live

1998 recording conducted by Fabio Luisi and also sung in French

(see review).

As with Don Carlos for Verdi, this opera is my most loved

Rossini score, both coincidentally the longest of each composer’s

works and both composed for the Paris Opéra. Partly because

of that I have taken somewhat longer to come to my conclusions

over this issue with several re-playings. Whilst Pappano starts

at a hectic pace to give a vibrant overture, a piece that was

the staple of every orchestra in the days when a concert comprised

an overture and concerto in the first half and a symphony in

the second, his tempi are not wholly consistent nor convincing.

Add a variable acoustic, seemingly dry at times and reverberant

at others, and the applause that could easily have been omitted,

and I had early doubts as to whether my love would last the

pace. With one French language rival, Gardelli’s, giving the

Troupenas edition of the score in full, Pappano chops major

chunks of the last act; this with twenty-five minutes or more

space on the third CD, my love was waning. Much would depend

on the singers.

The singing cast in this opera tends to depend in some measure

on the capacity of the tenor singing the role of Arnold and

its vocal challenges. In many ways I was satisfied with Sabbatini

on the Orfeo issue whilst recognising he was not perfect, his

tightly focused voice lacking some ping. On this recording the

American John Osborne has a much more mellifluous and freer

tone, floating a gentle head voice for his peak note and meeting

the other vocal hurdles with élan to go alongside tastefully

phrased singing, far superior to Gedda’s often forced tone.

The eponymous role has no arias as such but a forceful well-characterised

voice is vital to make a suitably dramatic impact on the performance

narrative. Not as full toned as Hampson on Orfeo, Finley is

a younger sounding Tell than either rival, but is a tower of

strength in bringing to life the evolving drama in all its twists

and turns, his French noticeably idiomatic and comparable to

the francophone Bacquier. The Australian Elena Xanthoudakis

in the trouser role of Jemmy, on whose head the apple has to

sit awaiting his, or its fate, is another vocal strength in

both quality of singing and characterisation. Overhanging the

role of Mathilde, Princess of the House of Habsburg, whose affiliations

are tested by love, is the performance of Caballé of the earlier

EMI set and whose quality is outstanding. Compared with Caballé,

Malin Byström is in a much lower league in both beauty of her

singing and characterisation; championship at best, certainly

not premiership. The minor roles are variable with some incisive

characterisations such as Marie-Nicole Lemieux as Tell’s wife

mixed with the odd blusterer. The chorus is simply outstanding

as only Italian choruses on their mettle can be, even when singing

French.

The booklet has a libretto side by side with a multilingual

translation, the extensive and informative introductory essay,

and Pappano’s background to the recording and his knowledge

of the opera, is likewise translated.

Robert J Farr

see also review by Gavin

Dixon

|

|