|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827)

Fifteen Variations and Fugue on an Original Theme in E flat major,

Op 35 ‘Eroica’ [25:33]

Twelve Variations on the ‘Menuett à la Viganò’

from Jakob Haibel’s Le nozze disturbate, WoO 68 [13:26]

Twelve Variations on the Russian Dance from Paul Wranitzky’s

Ballet Waldmädchen, WoO 71 [11:10]

Ten Variations on ‘La stessa, la stessissima’ from Antonio

Salieri’s Falstaff [9:44]

Eight Variations on ‘Tändeln und Scherzen’ from

Franz Xaver Süssmayr’s Soliman II [8:14]

Six Variations in D major, Op 76 [6:13]

Ian Yungwook Yoo (piano)

Ian Yungwook Yoo (piano)

rec. 25-26 July 2008, Glenn Gould Studio, CBC, Toronto, Canada

NAXOS 8.572160 [74:18]

NAXOS 8.572160 [74:18]

|

|

|

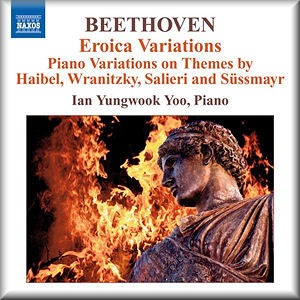

The cover presents a striking image: the conquering hero, immortalized

in stone, looks out over a sea of fire. He stands alone against

the flames, boldly unconcerned. It is a wonderful image of Beethoven

the warrior, the master of musical struggles.

The contents of this CD come from a very different side of Beethoven.

This recital showcases Beethoven’s witty side, his penchant

for virtuosic invention, and his growth as a creative mind.

These are six sets of themes and variations, only two of them

published. The other four are early works which reveal the genesis

of ideas and techniques which would later become the composer’s

mainstays. Any lover of Beethoven ought to hear this.

Pianist Ian Yungwook Yoo, who is qualified for the job by his

first-prize triumph at the 2007 Beethoven Competition in Bonn,

tackles the legendary ‘Eroica’ variations first.

He is clearly an advocate of ‘big,’ old-fashioned

pianism, and the powerfully sustained opening chord establishes

this immediately. But he also sets free his inhibitions, indulges

Beethoven’s violent dynamic changes (3:27-3:43), lets

the left hand interrupt lyrical moments such as that at 7:00,

and matches Beethoven’s playfulness smile-for-smile in

variations like the one beginning at 5:21. This is supreme musical

mischievousness!

The bulk of the CD is concerned with unpublished variations

on themes by other composers. None of these writers are remembered

with anything like the fondness we have for Beethoven, and (as

with the Diabelli Variations) we can safely say that Beethoven’s

achievements with these variations exceed the originals in every

case. Salieri’s opera Falstaff has been recorded

several times, including performances on Chandos and Hungaroton

and even a DVD, but none of the “originals” to the

other works here have been recorded. Indeed the catalogues at

Arkivmusic and MDT have no listings at all for CDs of music

by Jakob Haibel.

The primary interest of these works is as a fascinating catalog

of Beethoven’s early treatment of the variation format.

Theme-and-variations was arguably the central form of the composer’s

career: consider the mighty variation movements in the Third,

Fifth, and Ninth symphonies, the piano sonatas opp. 109 and

111, and the monumental Diabelli set. If you are at all fond

of those works, you should listen to the early Beethoven variations,

for they really do provide great insights into his evolving

language and his way of creating something stupendous out of

nothing.

I say “nothing” because one of the insights on offer

here is that Beethoven consciously chose bare, bland, maybe

even poor themes for his variations. The Diabelli waltz theme

is, in that sense, perfect for Beethoven’s purpose: if

you set it alongside Wranitzky’s dull Russian Dance, or

Haibel’s genial but forgettable minuet, or (dare I say

it) the Eroica tune, you see that they really are all cut from

the same cloth; the rhythmic similarity between Diabelli’s

theme and Salieri’s is truly striking. The themes are

canvases on which Beethoven paints; in fact they are rather

cheap canvases from the supermarket chosen in order to demonstrate

all the more clearly that the credit belongs solely to the painter.

Typical of this style is the Haibel set: immediately, with the

first variation, Beethoven leaps into a wholly different mood

and style. Not for him the classical-era plan of simply ornamenting

the tune with little decorations, then having the left and right

hands switch, then altering the melody by one or two notes.

Beethoven leaps in at the deep end. Already we can hear his

adventurousness and his conception of variations as transformative.

This structure will be taken to more profound heights in works

like the last piano sonata but even in the 1790s Beethoven was

writing “theme and transformations”.

The first variation of the Wranitzky set is more conventional,

but in exactly five minutes the theme is rendered completely

unrecognizable and the work becomes wholly Beethoven’s.

And there are vintage Beethoven moments all through these early

works, like his habit - to be highlighted in the piano and orchestral

Eroica variations - of leaving melodies hanging confidently

in midair halfway through, pausing, and then rolling in with

the resolutions. The luminous Wranitzky variation at about 3:35

presages some of Beethoven’s transcendent writing in the

last sonatas; the fact that Beethoven cannot even wait until

Salieri’s theme is over before beginning to toy with it

brought a smile to my face. The Salieri set, although a bit

monotonous, does introduce the classically Beethovenian idea

of bringing back the original theme at the end, subtly transformed.

The ‘Turkish march’ variations Op 76 make a delightful

encore.

The only real competitors in this quiet corner of the Beethoven

repertoire are Alfred Brendel on Brilliant Classics, John Ogdon

on EMI, Ronald Brautigam on Globe, and Gianluca Cascioli on

DG, though the last two are quite hard to find and indeed the

latter is out of print. Florian Uhlig on Hänssler has recently

recorded the Wranitzky set. The unpublished variations are probably

not interesting enough to merit duplicating if you already have

one of those recordings, although I should point out that Brendel

omits the Haibel and none of them can match the Naxos sound

quality.

There are many Eroica variations out there, and everyone will

have a favorite (Gilels looms large), but Ian Yungwook Yoo really

does bring everything to this performance: showmanship, drama,

great wit, playfulness, sensitivity (8:59-10:02, 15:11-17:20),

and superb technique. He is recorded in finer sound than any

competitor, although you will want to turn the volume up. He

is less sober than Bernard Roberts on Nimbus, more ‘grand’

and romantic than Jenö Jandó, and a full three minutes

slower than Brendel, to Yoo’s advantage; Brendel treats

the humorous and merely virtuosic variations with one fleet-fingered,

undifferentiated style.

For Beethoven lovers and aficionados his early variations are

essential listening and have greatly aided me in my listening

to his late masterworks in the genre. If you are a casual fan,

you may find this music to be of less obvious interest, since

so much of it is light, witty, and clever, rather than fiery

as the cover might imply. It is not ‘vintage Beethoven’

by any means. But hints of ‘vintage Beethoven’ are

to be heard in every work, and that is why real devotees of

the composer will find this volume fascinating.

Brian Reinhart

|

|