|

|

|

alternatively

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

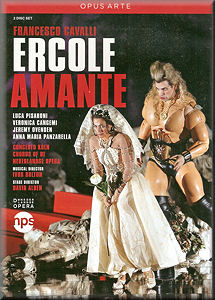

Francesco CAVALLI (1602-1676)

Ercole Amante (Hercules in Love)

Ercole (Hercules):

Luca Pisaroni (bass-baritone); Ercole (Hercules):

Luca Pisaroni (bass-baritone);

Iole: Veronica Cangemi (soprano);

Giunone (Juno): Anna Bonitatibus (mezzo);

Hyllo (Hyllus): Jeremy Ovenden (tenor)

Deianira: Anna Maria Panzarella (soprano)

Licco (Lichas): Marlin Miller (tenor)

Nettuno (Neptune)/Tevere (Tiber)/Spirit of Eutyro: Umberto Chiummo (bass); Bellezza

(Hebe)/Venere (Venus): Wilke te Brummelstroete (mezzo); Cinzia (Cynthia)/Pasithea/Spirit

of Clerica: Johannette Zomer (soprano); Mercurio (Mercury)/Spirit of Laomedonte:

Mark Tucker (tenor); A Page/Spirit of Bussiride: Tim Mead (counter-tenor)

Chorus of De Nederlandse Opera; Concerto Köln/Ivor Bolton

Stage Director: David Alden

rec. live, Het Musiektheater Amsterdam, 15 and 20 January 2009.

Extra features: Illustrated synopsis; Cast gallery; Behind the scenes with Johanette

Zomer; Behind the scenes with Luca Pisaroni; The making of Ercole Amante.

All Formats; All Regions. Picture Format: 16:9 anamorphic. Sound: 2.0 & 5.0

PCM

Subtitles in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Dutch

(also available on Blu-ray as OABD7050D)

OPUS ARTE OA1020D OPUS ARTE OA1020D  [2

DVDs: 261:00] [2

DVDs: 261:00]

|

|

|

This is an enterprising and welcome release; to the best of

my knowledge there is no other recording of the whole opera,

though

Lully’s ballet music for the Prologue and Finale are available

on a 2-CD set of that composer’s music for the marriage

of Louis XIV, on Accord 4429894. It’s not out of place

there, since Ercole Amante was composed to celebrate that

marriage and the ballet music was added by Lully, but I’ve

been waiting for a complete recording since hearing the opera

broadcast on BBC Radio 3, conducted by Gabriel Garrido at the

Ambronay Festival in 2006.

Indeed, there is not very much by Cavalli in the current catalogue:

even the famous Decca CD version of La Calisto seems to

have been deleted, apart from a few short excerpts on various

Janet Baker compilations, though there is a recommendable DVD

version (Concerto Vocale/René Jacobs, Harmonia Mundi HMD990900102;

the CD equivalent of that DVD also seems to be deleted, though

released as recently as 2006). Among currently available recordings

of Cavalli, I can recommend the Messa Concertata, performed

by Seicento and The Parley of Instruments/Peter Holman on a budget

Hyperion Helios CD (CDH55193) and the Coro Claudio Monteverdi

di Crema’s performance of his Vespers music for St Mark’s

under Bruno Gini (Dynamic CDS520), a useful pendant to the famous

Monteverdi Vespers of 1610.

The original production of Ercole Amante was two years

in the making and, at the time, it was the grandest show ever

performed in Europe - too grand, in fact, to be realised when

Cavalli arrived in Paris in 1660. He had been promised all the

latest gadgetry of La Salle des Machines, but this was not completed

for another two years and the opera had to wait until February,

1662. Luckily, Cavalli was able to offer something that he had

prepared earlier, Il Xerse of 1654, as a stop-gap. I haven’t

heard Il Xerse, but if it’s even a patch on Ercole,

or Cavalli’s better-known La Calisto, it should

be well worth recording. Perhaps Hyperion, who have recently

recorded Le Astuzie d’Amore by Cavalli’s contemporary

Cesti - a fine work and a fine performance, but no match for Ercole,

would oblige us. (CDA67771/2 - see my January, 2010 Download Roundup).

The librettist, Francesco Buti, took from the rather complex

account in Ovid’s Metamorphoses IX the essence of

the story of Hercules’ love for Iole, the jealousy of his

wife Deianira, the implacable hatred of Juno for the hero, Lichas’s

suggestion to Deianira that she give Hercules the shirt of Nessus,

the centaur whom he had killed and which would supposedly put

an end to his infidelity. The shirt certainly achieved its purpose,

but by killing Hercules; as he died he prepared his own funeral

pyre, which burned away his human part and left only that which

he had inherited from Jupiter, so that at Jupiter’s instigation

and with even Juno’s tacit approval, his divine form reigns

in the heavens eternally with Hebe as his consort.

Some details had to be omitted from the opera: even the state-of-the-art

Salle des Machines would have been hard put to portray the funeral

pyre without danger. Other details were added to extend the story,

such as the prologue and epilogue with their flattery of Louis

XIV, the part played by the God of Sleep, Somnus (here Italianised

as Sonno), and above all the love of Iole and Hyllus (Hyllo):

in Ovid, the dying Hercules merely commends Iole, who is carrying

his unborn child, to the care of his son Hyllus. In Ovid Juno

simply consents to Jupiter’s proclamation of Hercules’ apotheosis;

in the opera she becomes the agent of that transformation for

reasons which are not readily apparent. The story of her implacable

hatred of our hero, which led to his delayed birth - the subject

of one of Ted Hughes’ Tales from Ovid, his late-life

masterpiece - and the labours which she imposed upon him are

merely alluded to in the opera.

The Paris audience demanded dance and Cavalli’s fellow-Italian,

who had Frenchified his name to Lully, was on hand to supply

the necessary, thereby extending the length of the opera considerably.

The inclusion of the ballet also increases the demands of an

already demanding work, including a very large cast and orchestra

and the need for elaborate scenery and stage effects, all requirements

which are excellently met in this production. My analysis of

such a long opera is necessarily rather detailed: if you don’t

want the detail and want to cut to the recommendation, all concerned

do their best to make this a most enjoyable occasion.

That isn’t to say that there are not some scenes which

outstay their welcome and fail to make much of an impression

when they have been completed. A friend who saw a production

some time ago, though he is a fan of baroque opera, remembers

finding the music attractive but otherwise only that the work

needed some heavy pruning. In fact, the broadcast performance

by the Ambronay European Baroque Orchestra which I have mentioned

was quite heavily pruned. Some of the scenes stay in the memory

for perhaps the wrong reason, such as the comedy of trying to

wake Sonno (Somnus the God of Sleep) and keep him awake. I couldn’t

quite remember afterwards what part Sonno was to play in the

following action. (Juno ‘borrows’ him to put Ercole

to sleep for a time, but Mercury intervenes to wake him.) There’s

a parallel with that Decca recording of La Calisto, where

a lasting memory is that Hugues Cuénod steals the show

with his hilarious impression of an ill-tempered nymph.

The Prologue is an example of what a modern audience may well

find tedious, with its references to the glories of France from

the year dot, the sad recent wars and the joy of the new union

with Spain. Yet the prologue is essential to the opera, since

it sets it in the context of the marriage which it was originally

intended to celebrate, albeit somewhat belatedly.

Instead of Tevere (Tiber), during the opening sinfonia a

rather sinister-looking cardinal enters (Umberto Chiummo), reading

a book, looks up at the mural of the naked Hercules and crosses

himself in horror. Is he meant to represent Cardinal Mazarin,

Cavalli’s original patron, though he had died in the interim?

Or is his scarlet habit meant to represent the Sibyl’s

prophecy in Vergil’s Æneid to the Tiber foaming

with much blood?

Bella, horrida bella,

Et Thybrim multo spumantem sanguine cerno. (VI, 86-7)

In any

event, he becomes embroiled in the ballet, where his absurdly

long habit contrasts with the blue of the dancers

and the undulating

cloths which represent, presumably, the Seine and other French

rivers, in contrast with the Tiber. Tevere and Cinzia (Cynthia,

Johannette Zomer), assisted by the chorus, then deliver the prologue.

The quality of their contributions in such small roles augurs

well for the quality of what is to come. Chiummo is later allowed

to come more into his own as an impressive Nettuno (Neptune),

rescuing and lecturing Hyllo, and as the spirit of Eutyro.

Luca Pisaroni, who is to play Ercole (Hercules) first enters

in the ballet as a non-speaking, larger-than-life Louis XIV,

retiring to his nuptial chamber with a smaller and somewhat apprehensive

Maria Theresa. Some of the ballet gestures are unduly modern,

but I didn’t find this as great a problem as it is in some

other recent productions of baroque opera. Nor was I unduly put

out by Tevere’s periodic grimaces, Cinzia’s absurdly

bouffant hair-style - meant to remind us that she is the moon

goddess - or the squeals from the dancers as Louis disrobes his

bride, though I could have done without all of these.

What matters is the high quality of the singing from all concerned

and the success of the production in coming close to how the

spectacle must have appeared to the original audience: the lavishness

of the scenery first seen in the Prologue is maintained throughout

the production. Sometimes it seems an unnecessary chore to list

the names all those concerned in the booklet, but Stage Director

David Alden, Set Designer Paul Steinberg and Costume Designer

Constance Hoffman certainly deserve to be named: the success

of this recording is almost as much due to them as to Musical

Director Ivor Bolton, whose reliability at the helm of baroque

opera has almost come to be a cliché. With Bolton, Concerto

Köln, the Chorus of Nederlandse Opera and the production

team behind them, the principal singers have a secure backdrop

- physically and musically - against which to perform.

If anything, the end of the opera, the Ballet for the Stars (Ninth

Entrance, DVD2, tr.15) and the closing Galliard for the Stars

(DVD2, tr.17) which sandwich Ercole’s apotheosis are even

more spectacular than anything which has gone before. The courtiers

of le Roi Soleil, appropriately garbed in gold, make a striking

visual contrast with the preceding scenes among the ragged spirits.

At the beginning of Act 1 a huge blow-up suit and boots are brought

onto the stage in preparation for Pisaroni’s transmogrification

from Louis to Ercole. Later he acquires his famous club and the

Nemean lion’s skin. Any possible tendency to dismiss this

as kitsch is dispelled by the evident enjoyment with which he

achieves the transformation without the quality of his singing

suffering in any way. The way in which he manages to strut around

the stage without any vocal - or other - accidents is amazing.

Only at the end, when he appears transformed once more, this

time, gloriously, into an immortal, is he free of having to wear

this encumbrance.

He is the centre of attention from the moment when he appears

as Louis XIV to the end, when he joins Bellezza (Hebe) in the

Heavens (Act V, Scene 5, DVD2, tr.16). If I also name him the

vocal star of the recording, albeit rivalled by Veronica Cangemi’s

Giunone (Juno) and Anna Maria Panzarella’s Deianira, that

seems to be entirely appropriate.

The appearance of the Three Graces from flaps in a mural, on

which they are represented d’après Peter

Paul Rubens’ fleshy vision of them, is somewhat off-putting

but, again, the quality of their singing and especially that

of Venere (Venus, Wilke te Brummelstroete), whom they accompany,

more than compensates. Rather more off-putting is Ercole’s

drinking from an absurdly large six-pack of Heineken to fortify

himself but, again, the foolery in no way interferes with the

quality of his singing. In a production which largely refuses

to update the costumes to the present day, apart from the nether

half of Hyllo’s costume and the contents of his rucksack

(see below), irritations such as this and the decision to have

Mercury smoke a cigarette stand out all the more.

As Giunone (Juno) Anna Bonitatibus’s mezzo voice contrasts

with Venere’s soprano which we have heard immediately previously.

Equally importantly, we can believe from the acting how implacably

opposed the two goddesses are, without the acting detracting

from the quality of either’s singing. If Giunone has the

more powerful voice, that is an appropriate reminder of the extent

to which she shapes the action of the opera.

The following entr’acte (Fourth Entrance, DVD1, tr.8) represents

lightning and storms; I was not quite sure why the dancers had

to be dressed as and dance like large black birds. Perhaps the

original audience would have remembered more readily than I that

the crow was sacred to Juno - I had to search deeply in the garbage

heap of classical reference in the back of my mind to remember.

Nor was I too sure why Hyllo (Hyllus, Jeremy Ovenden) appears

in the first scene of Act II (DVD1, tr.9) blindfold and crawling

around the stage with a rucksack full of modern accoutrements

such as a bottle of Cola and a mobile phone. Perhaps we are meant

to contrast his sottish behaviour with that of his father Ercole,

but there is no textual or musical authority for this view of

Hyllo as an idiot. Nevertheless, once again the quality of his

singing and that of Iole (Veronica Cangemi) wins the day, as

does that of Tim Mead as the Page when he joins them. Mead almost

out-sings the principals among whom he also later appears as

the Spirit of Busssiride. Surely he deserves a larger part in

future.

Let me just mention some of the other distractions which I thought

unnecessary, if only to discount them in the final reckoning.

I thought that it was appropriate for Licco (Lichas) to appear

a picaresque character, but there is no reason for him to be

camped up and particularly not for him to attempt two sexual

attacks on the page. Once again, however, the quality of Marlin

Miller’s singing at least diminishes the distraction. At

the end it may seem unfair that he should be dragged down into

the underworld when he was unaware what the effect of the shirt

would be (Ovid says that Deianira handed it, unknowingly, to

an equally unknowing Lichas: ignaroque Lichæ, quid tradat,

nescia), but there is warranty for his punishment in Ovid,

who has him flung ‘more violently than [as if] from a catapult’ (tormento

fortius), into the waters of the Eubœan, where he becomes

a promontory.

As if we didn’t recall that Hercules was born very large,

beyond his term, that he strangled the snakes in his cradle and

that one of his labours was to take the world off the shoulders

of Atlas, a grotesque overblown baby mauling two snakes and a

manikin carrying the globe appear onstage in Act V. This is distracting,

but not fatally so.

At the end we return to the marriage bed which we saw at the

beginning (DVD2, tr.16); this time Wilke te Brummelstroete climbs

in as a buxom Bellezza (Hebe) with none of the chariness displayed

by Maria Theresa at the opening. Now it’s Ercole who looks

less than enthusiastic. The final track (DVD2, tr.17) is described

in the booklet as the eighteenth entrance, which suggests that

some of Lully’s ballet music has been omitted: we have

nos.1-7, 9 and 18, which is probably enough.

Actually, impressive as is the closing apotheosis and divine

marriage, two preceding scenes, one where Deianira laments her

lot and that in which Ercole dons the shirt and dies were, for

me, the most memorable parts of this performance. Any post-Monteverdi

composer worth his salt could write a good lament. The Lamento

d’Arianna is the sole surviving part of the lost Ariadne

opera; so successful was it that Monteverdi also transformed

it into a lament for the Virgin Mary. Deianira’s lament

for her lot in Act IV, scene 6 (DVD2, tr.8) runs his master’s

model pretty close, especially when it’s as well sung as

it is here by Anna Maria Panzarella - resplendent in a superb

costume and in equally superb voice.

When Hercules is dying in Act V, scene 4 (DVD2, tr.13) I wondered

at first if Pisaroni was not underplaying the part - it’s

not that I wanted silent-film-type over-the-top gestures, but

at first nothing seems to be happening. Someone has clearly been

reading Ovid, who states that at first Hercules resisted the

burning shirt with his customary courage - dum potuit, solita

gemitum virtute repressit - until he slowly became more and

more anguished and bloodied as he tried to tear it off. Full

marks to all concerned for the way in which the scene is carried

off.

I have not yet mentioned the quality of the contribution of Mark

Tucker as Mercurio (Mercury) and as the spirit of Laomedonte;

let me do so now. This is another singer who surely deserves

a larger part.

The direction of the camera-work contributes greatly to the success

of this recording. The picture quality is excellent, especially

if played on an HD-ready television with up-scaling. The images

are sharp, there is no motion blur and the colours are striking

and life-like. The sound, played in stereo via the television,

is more than adequate. Heard via a good audio system it’s

of CD quality. Some of the voices sound a little backward when

the singer is at the rear of the stage - for example, Venere

in Act I, Scene 3 (DVD1, track 6) and Giunone in the following

track/scene - but this is not a major problem and it is inevitable

in a live recording. I am currently considering converting to

Blu-ray, in which form this recording is also available, preferably

via a deck which plays SACDs, but recordings of this quality

prove that DVD is not dead yet.

The notes in the booklet are very helpful in setting the opera

in context. There is a useful illustrated 10-minute synopsis

on the first DVD, but it would have been more helpful also to

have had a printed synopsis in the booklet; you can find one

on the web, linked to this Opus Arte recording, here.

A little classical knowledge would help, too: I had to think

how, as Juno claims in Act I, scene 3 (DVD1, tr.7) Hercules had

offended her before he was born. (She tried to prevent his birth

because he was one of the many offspring of her philanedring

husband Jupiter, then she sent two snakes to kill him in his

cradle; he choked them both with his bare infant hands. We shall

be reminded of this later in the opera, but in a manner which,

as I have said, is rather grotesque.)

If, like me, you prefer to have both the Italian and a translation

in front of you - will it ever be possible for sub-titles to

do both simultaneously? - you can print out the Italian libretto

from the web here.

If you are looking to expand your experience of Cavalli - and

why not? - there is a Naxos recording of his opera Gli Amori

di Apollo e Dafne (8.660178/8) to which Robert Hugill gave

a mixed review,

and another Naxos CD of arias (8.557746), which Johan van Veen

broadly welcomed - see review -

as did Robert Hugill - see review.

Having listened to the aria CD on the Naxos Music Library, I

find myself in total agreement with those reviews. My personal

contribution is to reiterate my recommendation of the two CDs

of sacred music which I mentioned above, on Hyperion Helios and

Dynamic. More to the point of the current exercise, the DVD production

of Ercole Amante is at least the equal of any of these

- indeed, only the Hyperion performance of the Messa Concertata equals

it in performance terms and cannot contend with the visual excellence

of the Opus Arte DVDs.

Brian Wilson

|

|