Back

to Chapter 5

6

The London Philharmonic Orchestra

History 1932 until 1939 when it was

obliged to go into voluntary liquidation. The orchestra reforms and

is administered by the players themselves. J B Priestley, Jack Hylton,

Sir Henry Wood. Life in a self-managed orchestra. 1944 Sir Thomas

returns to his old orchestra. He leaves and in 1946 forms the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra. 1947 the author follows.

When the war started, in 1939, every

one in the London Philharmonic Orchestra felt very insecure; would

the concerts and recordings already booked, or planned, take place?

Some of the players were already expressing doubts as to whether the

shaky financial basis upon which the orchestra was founded could possibly

survive. In fact it was not long before London Philharmonic Ltd. was

obliged to call the creditors to a Liquidation meeting.

The Company had been founded by Sir

Thomas Beecham in 1932, with himself as Artistic Director, and with

a number of well-born and wealthy music lovers as co-directors. At

the meeting it was left to Sir Thomas to explain that there was no

money at all, and therefore no one would get any. He used his famed

eloquence and charm to impart this disagreeable information, and somehow

succeeded in soothing and placating his audience. The players in the

orchestra, all of whom were owed money for unpaid fees, made no opposition

to the voluntary liquidation of the company; their main concern was

to keep the orchestra in being.

Almost at once the musicians decided

to form a new company, with themselves as shareholders. Sir Thomas

gave his blessing, the company was created and named Musical Culture

Limited. A Board of Directors was elected and staff engaged to administer

the affairs of the orchestra. Charles Gregory, a very fine player

who had been Beecham’s principal horn for some years, was elected

Chairman of the Board. He was held in considerable respect, and, as

I was to learn for myself a few years later, he was a man of imagination

and integrity. Thomas Russell, one of the viola players, also elected

to the Board, became their Secretary and Business Manager. The orchestra

then set about looking for engagements.

In 1940, after undertaking a few concerts,

Sir Thomas left for the USA, leaving the members of the orchestra

to take full responsibility for the administration and artistic control

of the newly re-formed London Philharmonic Orchestra. The full story

of this remarkable achievement is contained in two books by Thomas

Russell, Philharmonic and Philharmonic Decade, essential

reading for anyone interested in the development of orchestral music

in Britain.

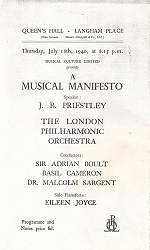

Because of his stirring wartime broadcasts

J.B.Priestley, the famous author of The Good Companions and

of many successful novels and plays, had become a household name.

After a chance meeting with Tom Russell he became concerned about

the difficulties the orchestra was facing and decided that something

needed to be done to rally support for it. He suggested that a concert

be put on that would attract a prestigious audience, and which could

be used to generate funds from the general public. It should be called

‘A Musical Manifesto’. Sir Adrian Boult, Basil Cameron and Dr Malcolm

Sargent (he did not become Sir Malcolm until 1947) readily agreed

to conduct one item each, and Eileen Joyce was willing to play the

Grieg Piano Concerto.

|

|

Click

for larger picture

|

On the night of the 8th of July 1940,

the Queen’s Hall was full, which was unusual at that early stage of

the war, before everyone had become accustomed to the blackout. The

programme for this auspicious occasion was: Elgar’s Cockaigne Overture,

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, Eileen Joyce played the Grieg Piano

Concerto, with Basil Cameron conducting and, after the interval, Dr

Sargent conducted the Second Symphony by Sibelius. The concert started

with Priestley making one of his most effective speeches, a mixture

of homespun philosophy and good Yorkshire hard-nosed practicality;

this was his Musical Manifesto. It was well received by the capacity

audience, and widely reported by the press. In the next few weeks

thousands of donations were received, ranging from postal orders for

a few shillings to very substantial cheques. This was the turning

point for the orchestra, putting it (for the time being) in a relatively

strong financial position.

Priestley’s speech and part of the

performance of Cockaigne Overture are re-enacted in a film

the orchestra made in 1941, called Battle for Music. It was

quite widely shown at the time and is still occasionally shown on

TV. The film tells of the trials and tribulations the LPO and the

members of the orchestra experienced in the early years of the war

and how they triumphed in the face of adversity. Some of the musicians,

in particular members of the Board, ‘act’ their role in this story

with varying degrees of success. As well as Priestley, Dr. Malcolm

Sargent, Sir Adrian Boult and Jack Hylton also have ‘acting’ roles.

Battle for Music is not up

to Hollywood standards, but it fulfilled its purpose at the time and

remains an interesting and entertaining historical document. Such

shortcomings as it has are outweighed by the honesty of its intent

and the excellence of the performances of the music, conducted by

Dr. Sargent, Constant Lambert, and Warwick Braithwaite, with Eileen

Joyce and Moiseiwitsch as soloists.

The film ends on a high note. Superimposed

over newsreel footage of Sir Winston Churchill inspecting the troops,

to the accompaniment of Land of Hope and Glory, are the following

words:

An Orchestra is like a country.

It has its triumphs, its disasters and despairs. Only with unity and

faith can it become great.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra

has these qualities. These musicians played on during the darkest

days and blazed the trail for other fine orchestras.

They showed how musicians themselves

can organise their own lives and their own art. This spirit, which

inspired this orchestra to struggle against adversity, to adapt their

lives courageously to changing conditions, cannot be defeated.

The London Philharmonic becomes

the treasured possession of the British people.

Further support for the orchestra

came from a most surprising quarter. Jack Hylton, formerly a famous

dance-band leader, was now an impresario, with interests in the theatre

world. He undertook to present the LPO for a week at a time in a number

of large theatres all over the country. These theatres usually presented

either Music Hall (later to be known as Variety), or companies touring

successful musical comedies, following their West End run.

Hylton saw to it that the concerts

were well advertised, and took especial care over the presentation

of the orchestra. He had a rostrum built, that could be assembled

in every theatre the orchestra visited, with sides and a ceiling,

so that all the sound did not get lost up in the ‘flies’, making it

much better acoustically than orchestral performances on theatre stages

usually are. The whole presentation was rather more attractive than

in many of the conventional venues in which concerts were given.

Each week there was a concert every

evening and one on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons as well. These

concerts were extremely successful, playing to full houses virtually

the whole time. A great many of those attending the concerts had never

seen or heard a full symphony orchestra before. Their enthusiasm for

this new experience was heart-warming.

When I had accepted Mr Haines’s offer

of a three weeks’ engagement with the LPO I had no idea of what I

was letting myself in for. Perhaps this was fortunate; fools rush

in where angels fear to tread.

My first engagement with the LPO was

at the Royal Albert Hall on Sunday, the 9th of May 1943. There was

a rehearsal at 10.00, and a concert at 2.30. George Weldon (I had

played for him before in the Wessex) conducted a mainly Tchaikovsky

programme that included the ever popular 1st Piano Concerto, and the

Theme and Variations from the Suite in G.

Within the first few minutes I realised

that this was something very different to anything I had experienced

before. The quality of the string tone was much better, and the range

of dynamics throughout the orchestra far greater – ppp really

did mean very softly, and because of the number of string players

and the volume of tone they produced, fff was very, very loud.

To be playing in the Royal Albert Hall! I had only been there previously

to attend Prom concerts when I was still a student, and now to be

in this exalted company! The few important solo passages went reasonably

well, so I left at the end of the concert on quite a ‘high’.

|

|

Click

for larger picture

|

Early on Monday morning we set off

for what for me was to be the first of three of these ‘Hylton’ weeks.

We travelled to Norwich by train; in the afternoon there was a rehearsal

and at 7.30 a concert. This was followed by seven more concerts that

week, each with a different programme. With that number of concerts

there was not time for even one rehearsal for each performance, but

as the orchestra had played the works many times, in most cases with

these same conductors, and as they were very good players anyway,

the results were quite satisfactory. For me the situation was rather

different; all but a handful of the pieces we played were unknown

to me.

Those pieces that were rehearsed were

usually just ‘topped and tailed’, and only the tricky passages played

through, giving a novice, such as I was, only a rough idea of the

whole work. If one does not know the music and the conductor’s beat

is at all unclear (by no means an infrequent event), it can be difficult

to know whether they are beating two or four beats to the bar; or

know what they are doing at the end of a pause, or at a ‘cut-off’,

when there is a sudden silence in the music. It is all too easy to

find that you are the only one left playing when everyone else has

stopped, or, worse still, you have come in loudly all on your own

– that, for some strange reason, is called a ‘domino’. This can be

amusing to one’s colleagues, especially if it is a particularly high

or low note, or results in a terrible strangulated sound, as the player

seeks to suppress the unwanted intrusion. It is never anything but

the source of acute embarrassment to the player. The pieces that went

unrehearsed I had to sight-read at the concert. Skating on thin ice

is a less hazardous undertaking! Dazed and exhausted I got to the

end of the week, the adrenaline pumping hard.

On Saturday evening, after the second

concert that day, we returned to London, arriving back in the early

hours of the morning. Sunday morning dawned much too early for me;

at 10.00 we were rehearsing again in the Royal Albert Hall (RAH) for

the concert that afternoon.

Monday morning found

us on the train again, this time bound for Northampton, where we had

another week with eight concerts. I found the second week a little

easier; I had played a good deal of the music once. But occasionally

overconfidence and tiredness led to mistakes; I also had more time

to contemplate how much I needed to learn, if I was to match the accomplishment

of my colleagues. At the end of the week, back to London again arriving

late on Saturday night with only a few hours before another rehearsal

and concert in the RAH – and more new

music to learn. Then, early on Monday morning we were

off again, this time to Newcastle for a repeat of the previous two weeks.

I now started to worry whether I would be offered any more work with

the orchestra, or if this would prove to be just a flash in the pan.

I didn’t feel too confident about what I was doing, but at least I now

knew what page I was on – most of the time.

On Friday, as I was leaving the stage

at the end of the concert, Charlie Gregory, the Chairman of the Orchestra,

stopped me, and said, ‘Can you spare a moment? I’d like to have a

word with you.’ My heart sank and, as usual, I feared the worst. ‘They’ve

had enough’, I thought. When I heard Gregory say ‘How would you like

to join the orchestra, as our second clarinet?’ the gates of Heaven

opened, and I heard the sound of the Great Trumpets! ‘Oh! Yes, that

would be wonderful! Thank you.’ That was one of the best moments of

my life. I could hardly believe my ears, or really take in the tremendous

opportunity I was being given.

As usual we returned to London on Saturday evening. On

Sunday, 30th May 1943, we had another concert in the RAH. It was also

my eighteenth birthday, and I was in luck – it was

a very special concert –

|

|

Click

for larger picture

|

Sir Henry Wood conducted, and the soloist was the very

fine pianist, Solomon, a truly great artist. This was the first time

I played for Sir Henry, though I had heard my father speak about him

many times. In fact I always felt that my father was rather pleased

with his impersonation he liked to give of Sir Henry. Since my father

retained his Russian accent all his life even though he came to Britain

as a young boy, and Sir Henry spoke with a slightly Edwardian/Cockney

accent, the impression he gave of Sir Henry was none too accurate.

Sir Henry belonged to the ‘no-nonsense’

school of conducting. There was nothing flamboyant, or showy, about

his style. He used a longish, rather thick baton, and gave a good

clear beat. He concentrated on getting a precise performance with

firm rhythm, clean attack and ensemble, and good orchestral discipline.

His performances did not enthral you, but pleased with their honesty

and straightforward musicality. ‘Timber’, as he was known affectionately

in the profession, had a passion for establishing good habits. He

used to stand at the entrance to the platform at the Queen’s Hall,

with a tuning fork, which he struck as each player went past him.

The musician would then play his ‘A’ (the note the whole orchestra

tunes to, usually sounded by the oboe). I am told that he was never

heard to say ‘flat’, but that quite frequently he would say, in his

rather nasal voice, ‘shaaarp!’

He believed that a three hour rehearsal

should last three hours – there was no attempt to get the goodwill

of the orchestra by finishing early, a device employed by some conductors.

He had a very large watch, which he used to put on his music stand.

If he had completed the music to be rehearsed by ten minutes to one,

he would start at a place that allowed him to continue until one o’clock.

Keeping a careful eye on his watch, he would stop exactly at one o’clock,

whether this made good sense musically or not.

He also liked his musicians to mark

in their music any instructions he gave them. My father had a congenital

dislike for writing anything in the part that would remind him, or

anyone else using that part in the future, of any changes, additions

or corrections that had been made, preferring to rely on his memory.

Noting a lack of activity, when my father should have been busily

inserting some instruction, Sir Henry said, ‘Mr Tschaikov! Remember!

– a bad pencil is better than a good memory’.

That concert on my 18th birthday, conducted

by Sir Henry Wood, was the beginning of the most exciting and important

period of my life. At that age with my background I might have expected

to go to university, except that I had not acquired the academic qualifications

required, or

|

|

Click

for larger picture

|

the desire to acquire them. Instead, between 1943 and

1947 the LPO served as my university. Here I not only received a wonderful

musical education playing for some of the finest conductors from the

pre-1939 war years, alongside first-class musicians, but also a schooling

that provided a unique foundation course in living, for which I have

been grateful all my life.

In May 1945, at the cessation of hostilities

in Europe, there were still only three London orchestras: the London

Symphony, the London Philharmonic, and the BBC Symphony Orchestras.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra did not return to London until September

1945 and the London Symphony Orchestra was at a rather low ebb, financially

and artistically. The LPO with its dynamic and imaginative management

was able to take the lead in bringing back to London’s musical life

the international element that had been missing during the war years.

Tom Russell, with admirable foresight, had already booked some outstanding

conductors and soloists prior to the end of the war. We were off to

a flying start and for the next few years a number of very fine artists

who had not played in Britain since before the war were engaged by

the LPO.

For a very young musician, such as I

was then, the opportunity to work and associate with musicians like

Sir Thomas Beecham, Bruno Walter, Eduard van Beinum, Victor de Sabata,

Jaques Thibaud, Heifetz, Francescatti,

Fournier, Gendron – the list is endless – was

incredible.

Playing in the LPO as well as being

extremely enjoyable and rewarding musically was for me a profoundly

enriching learning experience. The structure of the LPO at that time

led to everyone being involved to a far greater extent than is normal.

Nearly everyone took part in the quite frequent orchestral meetings

at which important decisions on what course of action the orchestra

should take were discussed. Naturally, the members of an orchestra

will come from a great variety of backgrounds, educationally, socially

and economically and hold very different political views.

Age plays little part in the position

that a musician may hold within his section so that an outstanding

and exciting young violinist may become the Leader of the orchestra

when he or she is still only in their early or mid-twenties, whilst

players sitting at the rear of the section may have had thirty or

more years experience. The principal flautist, who has played with

the finest conductors for a lifetime, may be sitting next to a brilliant

young principal oboist just out of Conservatoire. While this is always

accepted as far as musical ability is concerned, when it came to the

discussions at meetings the ‘young’ and the ‘old’ – roughly those

over and under forty – opposed each other fairly regularly. It was

rather more serious when there was a difference of opinion between

those with very strongly held but opposing political points of view.

On these occasions age would play no part. The older and younger players

would join together in line with their political convictions.

This greater involvement in the affairs

and running of the orchestra revealed all these differences of background,

age and opinion quite starkly and increased the stress, frustration

and the highs and lows that are a normal part of a musician’s life.

As a result the virtues and failings in one’s own character, and those

of ones colleagues, could be on display for all to see. The pull of

personal ambition versus responsibility to the group, the courage

to take an unpopular stand, and not run for cover when a decision

one had supported turned out to have been mistaken, had to be faced.

I saw all those qualities and faults

of character that I was to meet throughout my life, and see at first

hand the effect virtues and vices had on our communal life. One witnessed

courage and determination contrasted with cowardice, duplicity and

betrayal; tolerance, kindness and sensitivity, as well as bigotry

and a brutal disregard for the feelings of others. Sometimes hard

decisions had to be made. Loyalty and friendship were tested. One

did not always come up to the mark in one’s own estimation, and, worse

still, one failed the test of the good opinion of one’s fellows.

Feelings can run pretty high in an

orchestra and sometimes lead to bitter disputes between colleagues

so that players obliged to sit next to one another within a section

may not be on speaking terms for a while – possibly for years. Yet,

even when dislike is so great that messages or instructions have to

be passed through a third party, musicians will play together with

a sweetness and unanimity that suggests that they are lovers.

For most of the 1940s the LPO was

generally thought of as a ‘left-wing’ orchestra, largely because its

members had elected Thomas Russell and Charles Gregory, both Communists,

to the Board of Directors. With Tom Russell as the Business Manager

(later General Manager) and Charlie Gregory as Chairman of the Board

of Directors, their influence was indeed considerable.

As a very young man I was attracted

by the idealism and intellectual vigour of both these men, especially

Gregory, and also by other Communists in the orchestra, who were fine

players and set an example I wanted to emulate.

In view of the immense changes that

have taken place in Eastern Europe it is worth recalling that this

was wartime, and that the Soviet Union was our ally. Uncle Joe, the

now despised and rejected Joseph Stalin, was a popular figure. Throughout

the world, and especially in Europe and the USA, a considerable number

of the most outstanding creative and performing artists had joined

the Communist Party. In 1944 I did so too. But following a ‘party

line’ of any kind is not something for which I think I am suited and

I proved to be a difficult, recalcitrant and rather short lived member.

It is not surprising that the LPO

was not too popular with the old-guard arts hierarchy. Perhaps, even

more than the spectre of a ‘red’ orchestra in its midst, the knowledge

that the members of the orchestra alone were responsible for its management

decisions and successful artistic policy sent shivers down the spine

of those who felt that musicians who play instruments should stick

to doing just that, and leave management and artistic decisions to

their betters (who don’t dirty their hands with violas, trumpets,

or the like). Sadly, this same attitude can still be heard today from

some of the backwoodsmen amongst our critics and administrators.

Tom Russell had both flair and insight;

and he had the energy and drive to achieve his objectives. As an administrator

he lacked the patience for the humdrum chores of everyday office routine;

he was more concerned with ideas, and when those around him in the

office did not check carefully there could be quite serious mistakes.

I have always found it ironic that the LPO dismissed Russell, many

years later, not for any mistakes he had made or any lack of ability,

but because he went to China for his holiday! But this did not stop

the Orchestra from taking advantage of Russell’s visit, and the contacts

he had made. They were the first British orchestra to tour China.

Towards the end of 1944, several weeks

before the Annual General Meeting I received the notice and the audited

accounts. It was the first time I had ever seen accounts and so they

were a complete mystery to me. I assumed that everyone else would

understand them, so I decided to take professional advice. I phoned

the chap who looked after my income tax returns (my only contact with

the world of finance) and he agreed to have a look at the accounts

with me. Like many accountants he was a serious man, and as he examined

the LPO accounts his face assumed an even more serious expression.

It seems that there were a number of entries that in his view required

questioning. His advice was that I should not under any circumstances

agree to the accounts before I had received satisfactory answers to

the questions he told me I should ask.

I expected that at the AGM the older

and more experienced members of the orchestra would be leaping to

their feet and peppering Tom Russell with questions about the balance

sheet. But there wasn’t a murmur from anyone. Always willing to rush

in when caution might be wiser, I thought I might as well put in my

pennyworth. I stood up and asked a couple of questions. Consternation!

Mr Haines, the Assistant Secretary, was dispatched to seek further

information. On his return one or two more searching questions caused

increasing discomposure, until, after his third attempt to find evidence

to silence this unwanted flow of questions, Tom Russell decided to

throw himself on the mercy of the meeting. It seems there was really

nothing to worry about; the cause of the apparent inconsistencies

was a move by the accounts department from the basement to the second

floor. In the process one or two of the books had been mislaid, nonetheless

he could assure the meeting there was absolutely nothing to worry

about. After a short discussion he asked for a vote of confidence,

which he received, though not without some dissent. The democratic

process has always appealed to me as the cut and thrust of debate

is natural to my temperament. The LPO provided the ideal environment

in which it could flourish.

Though the orchestra’s artistic policy

was splendid, inattention to detail had led to a decline in our financial

position. On a previous occasion, before I joined the orchestra, the

players had had to make sacrifices to keep the orchestra afloat. It

looked as if this might occur again. At one meeting this question

was the subject of considerable concern. Various solutions were put

forward: we should play programmes that did not require the engagement

of costly extra players, especially when we played in smaller halls

on tour; we should engage conductors whose fees were relatively modest.

These suggestions so infuriated one of the members that he stood up

and declaimed in a very loud voice, his face red with indignation,

‘We must never make artistic concessions. We should take Maestro de

Sabata to every fishing village in Britain.’ This piece of high-flown

rhetoric referred to the remarkable Italian conductor, Victor de Sabata,

who conducted the orchestra frequently at that time. Unfortunately

Maestro de Sabata liked programmes that included works for a large

orchestra, requiring additional wind and percussion players and extra

rehearsals, making his visits extremely costly.

This suggestion seemed so absurd to

me that I felt it was time to put forward a solution. Tom Russell

had a fairly large staff, some thought too large, and had attracted

a number of interesting, valuable and worthy people around him. Each

time I went to the LPO offices in Welbeck Street it seemed that their

number had grown. With tongue firmly in cheek I said, ‘I think I have

the answer to our difficulties.’ All heads turned towards me. ‘Why

don’t we increase the office staff to forty, and send a trio on tour?

That way we could balance the books!’ My suggestion met with a variety

of responses. Some of my colleagues smiled, a few laughed; others

looked incredulous; several appeared to be about to have an apoplectic

fit. I learnt that it is dangerous, when one is young, to address

one’s elders and betters in this way. My performance in the orchestra

was listened to with increasingly critical ears. And fault was found

– because, of course, fault there was. But I weathered the storm,

and remained unrepentant.

When, in 1944 Sir Thomas Beecham returned

to his old orchestra he found that it was now managing

itself very successfully. After a year or

so his need to be able to be in charge of everything

to do with the orchestra made it increasingly difficult for him to work

together with the orchestra’s elected management. Reluctantly the orchestra

and Sir Thomas parted company. By 1946 he had formed the Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra (RPO) and in 1947 I left the LPO and started playing in his

new orchestra.

This was a step into a very different

environment. Now I was not one of a group of musicians making decisions

about their own future. In the RPO I no longer had any part in the

management. However, there were benefits: I was paid considerably

more, I was playing in an even better orchestra with some of the most

outstanding woodwind players at that time. And above all I would be

playing a great deal of the time with one of the greatest conductors.

The following years were to be probably the happiest of my musical

life

Chapter

7

Chapter

7