|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

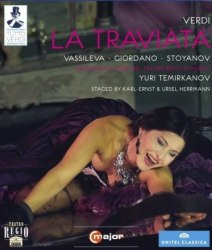

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

La Traviata - Opera in three acts (1853)

Violetta Valery, a courtesan - Svetla Vassileva (soprano); Flora,

her friend - Daniela Pini (mezzo); Annina, her maid - Antonella Trevisan

(soprano); Alfredo Germont, an ardent admirer - Massimo Giordano (tenor);

Giorgio Germont, his father - Vladimir Stoyanov (baritone); Gastone,

Visconte de Letoirieres - Gianluca Floris (tenor); Doctor Grenvil - Roberto

Tagliavini (bass); Baron Douphol, an admirer of Violetta - Armando Gabba

(baritone)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro Regio di Parma/Yuri Temirkanov

Stage Directors: Karl-Ernst Herrmann and Ursel Herrmann; Set and

Costume Designer (original), Karl-Ernst Herrman

Video Director: Tiziano Mancini

rec. live, Parma Verdi Festival, 16-20, 22 October 2008

Sound Formats: DTS-HD MA 5.1, PCM Stereo; Filmed in HD 1080i; Aspect

ratio 16:9

Booklet languages: English, German, French

Subtitles: Italian (original language), English, German, French,

Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Japanese

Also available in DVD format

C MAJOR BLU RAY 723704  [133:00 + 11:00 (bonus)]

Numbered eighteen in the Tutto Verdi (‘All Verdi’)

series, La Traviata is the most popular of Verdi’s operas.

It comes in at number two of all performed operas. It was premiered

at La Fenice, Venice on 6 March 1853, a mere six weeks after Il

Trovatore at the Apollo, Rome. This was because of the delay in

completing Il Trovatore following the death of its librettist,

Commarano before he had completed his work. Consequently Verdi composed

parts of both operas contemporaneously, quite a challenge considering

the differences in key, and particularly in the orchestral patina.

Even before this opera, the last staged of Verdi’s great middle

period trio, the composer his fame assured, could, both artistically

and financially, have afforded to relax. Giuseppina, his partner and

later wife appealed to him to do so. His artistic drive allowed no

such luxury. Whilst on a visit to Paris where the two enjoyed their

life together without the intrusions at Bussetto, the composer had

seen, and been impressed, by Alexander Dumas’s semi-autobiographical

play La Dame aux Caméllias based on the novel of the

same name. The subject appealed to him, but he recognised that it

might have problems with the censors. Even before the choice of subject

was made it was decided that Piave, resident in Venice, was to be

the librettist for the new opera for La Fenice. Verdi put off the

choice of subject until the preceding autumn, constantly worrying

the theatre about the suitability of the available singers. The theatre

in their turn wanted to get the censor’ approval of the subject

to satisfy their own peace of mind. Piave produced at least one libretto

that Verdi turned down before he finally settled on Dumas’s

play. La Traviata was the most contemporary subject he ever

set, embattled as he constantly was by the restrictions of the censors,

something that Puccini and the later verismo composers never had to

face.

Having spent the winter worrying about the suitability of the soprano

scheduled to sing the consumptive Violetta, Verdi was also upset that

La Fenice had decided to set his contemporary subject in an earlier

period thus losing the immediacy and relevance that he intended. Verdi

was correct in worrying about the censors and the whole project was

nearly called off when they objected. As to the singers, all went

well at the start and at the end of act 1, with its florid coloratura

singing for the eponymous soprano, Verdi was called to the stage.

The audience was less sympathetic to the portly soprano portraying

a dying consumptive in the last act; they laughed loudly. The tenor

singing Alfredo was poor and the baritone Varesi, who had created

both the roles of Macbeth and Rigoletto thought Germont below his

dignity and made little effort. Verdi himself considered the premiere

a fiasco. He did, however, compliment the players of the orchestra

who had realised his beautifully expressive writing for strings, not

least in the preludes to acts 1 and 3. Although other theatres wished

to stage La Traviata, Verdi withdrew it until he was satisfied

that any theatre concerned would cast the three principal roles, and

particularly the soprano, for both vocal and acting ability. The administrator

of Venice’s smaller San Benedetto theatre undertook to meet

Verdi’s demands. He promised as many rehearsals as the composer

wanted and to present the opera with the same staging and costumes

as at the La Fenice premiere. Verdi revised five numbers in the score

and on 6 May 1854 La Traviata was acclaimed with wild enthusiasm

in the same city where it had earlier been a fiasco. Verdi was well

pleased by the success, but particularly the circumstances and location.

La Traviata is now recognised not merely as one of Verdi’s

finest operas, but one of the lyric theatre’s biggest hits.

In terms of its popularity worldwide it is second only to Mozart’s

Die Zauberflöte in the canon of most performed operas.Much

of the success of any performance depends on the diva in the title

role. First she must look the part. Gone are the days when an overweight

Violetta is accepted as dying of consumption in act three. There was

hilarity at the premiere and such a situation today would bring even

more adverse audience response when the expectations are for singing

and acting as being vital necessities in the realisation of a role.

Second, the Violetta must be able to bring off the diverse vocal demands

of the three acts. In this performance Svetla Vassileva certainly

has the figure du part. Add the opulent costumes and an appealing

stage presence and she is off to a flying start. Each act of La

Traviata makes its own particular vocal demands on the soprano

singing the role of Violetta. Act one demands vocal lightness and

coloratura flexibility, particularly for the demanding finale of E

strano … Ah, fors’e è lui (Ch.9) and Follie

… follie! (Ch.10). In this performance cabalettas and second

verses are eschewed and this shelters her a little from the coloratura

demands which, while being adequate, are not her strongest suit.

For the first scene of the second act a fuller tone of voice is needed,

capable of wide expression and some power as Alfredo’s father

confronts Violetta and turns the emotional screw. Here Vassileva comes

more into her own in vocal heft, variation of colour and expression

as she resists Germont’s demands that she forsake Alfredo. She

stands up to him and wrings the emotion in Non sapette telling

Germont how much Alfredo means to her and she is a sick woman (Ch.15).

Then, after emotionally conceding she will forsake Alfredo, and being

embraced by Germont, she acts and sings with even better expression

and characterisation as she writes to Alfredo and deceives him, leaving

him to meet his father, all the time acting with conviction in terms

of facial expression. In act three she really rises to her histrionic

and vocal peak, bringing taut emotion to her words and acting with

her whole body. These qualities are particularly called on as Violetta

recites the phrases in Teneste la promessa … Addio

del passato (Ch.33) as she reads Germont’s letter indicating

Alfredo’s return and she realises it is all too late. After

Alfredo’s arrival, and their duet Parigi, o cara, with

its echoes of their declarations of love in act one, when both singers

caress Verdi’s phrases with real feeling (Ch.36), and after

Germont has arrived and embraced her as a daughter (Ch.38), Vassileva

pulls the heart-strings with even greater poignancy. It is one of

the most heart-rending duet passages in all opera, as the soprano

has to fine her voice as she gives her lover a portrait of herself,

requesting he pass it to the virgin he will marryPrendi quest’e

l’immagine (Ch.39), before finally raising herself from

her bed for one final dramatic vocal outburst as she collapses and

dies in his arms. If achieved with the vocal and histrionic conviction

that it gets in this performance it is guaranteed to leave not a dry

eye in the house; nor by the applause at the curtain and the flutter

of handkerchiefs did it in Parma in 2007.

I have devoted much space to Svetla Vassileva’s Violetta, as

her interpretation, together with the costume and sets, is the strength

in this performance. As Alfredo, Massimo Giordano spends too much

time in can belto mode, talking at Violetta rather than

to her. The exception is the act three-duet Parigi o cara

(CH.36) where he shows that he can sing softly and caress a Verdian

phrase; together with his soprano this duet becomes the vocal and

emotional zenith of this performance.

Vladimir Stoyanov as Germont sings strongly, but without much tonal

variation and hardly looks the part. The verse No, non udrai rimpovera

that follows Germont’s appeal to his son to return to Provence,

is cut. Neither principal man is helped in the first two acts by conductor

Yuri Temirkanov’s rather hard-driven approach, one he softens

for act three and where he really milks the pathos and which adds

to those tears.

The production directed by Karl-Ernst and Ursel Hermann goes back

to the late nineteen-eighties and has seen service in several centres.

The costumes are opulent, more fin de siècle than that

of the composition, but wholly illustrative of the Parisian demi-monde.

Some of the frolics in act one are over the top whilst that in act

two scene two for the gypsy’s dance is rather crude and not

particularly in tune with the music. The mise-en-scène

for act two scene one makes up for a lot: I will not spoil the story

with the detail.

A traditional production, in mainly colourful and elegant sets and

costumes, is graced by a very well acted and sung interpretation of

one of opera’s most demanding title roles.

Robert J Farr

See also review of the DVD release by Dave Billinge

|