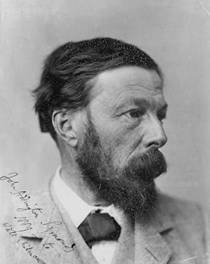

Ian

Venables: At Malvern

A

Pastoral or a Confessional Poem?

Rob Barnett in

a review

on MusicWeb International suggests that At Malvern

is “all moonlight and the lapping of cool waters.” On one

level this sums up the song’s mood, but it fails to intimate

the considerable emotional depth of the poem and its musical

setting. The liner note provided with the CD also down-plays

the true nature of this piece – it suggests that the poet

has “evoked the calm and serenity of Malvern in the 1860’s

where little could be heard, but the sounds of nature and

the distant bells of the famous priory”.

I believe that

this misses the point of the poem. What may seem to be a pastoral

idyll is in fact a cry from the heart of a poet who is suffering

from confusion, frustration and angst: it is played out against

the rural backdrop of the Malvern Hills. This dichotomy is

a sentiment that is well expressed by both the words and the

music.

In order to gain

a deeper understanding of the poem it is necessary to consider

a few relevant background details of the life and to a very

limited extent, the times, of the writer and poet: this is

not the place for a full biography.

John Addington

Symonds was born in Bristol on 5 October 1840. After a private

education there, he went to Harrow School. From a young age,

Symonds was considered to be delicate and typically did not

take an active part in the games and sports activities of

the school. Furthermore, he did not appear to be a particularly

promising student. In 1858 he went up to Balliol College Oxford.

He was to remain here as both a student and a tutor for some

time and settled into an academic routine. In 1862 he was

elected to an open fellowship at Magdalen. From that time

onwards he began to make his career as an academic and a writer,

as well as being an early campaigner for gay rights.

There are three

critical issues which affected his life at this time. Firstly,

the headmaster of Harrow, Charles Vaughan had an ‘affair’

with one of the boys. This had upset Symonds because it seemed

to go against his nascent idealisation of homosexual love.

In 1859 he revealed the gossip about Vaughan to a friend during

a discussion about ‘Arcadian Love’. This friend persuaded

Symonds to tell his father, Dr John Addington Symonds, who

subsequently insisted that Vaughan resign. Naturally, this

turn of events upset the young man, as he felt that he was

responsible for the headmaster’s disgrace and the ending of

his career.

There are three

critical issues which affected his life at this time. Firstly,

the headmaster of Harrow, Charles Vaughan had an ‘affair’

with one of the boys. This had upset Symonds because it seemed

to go against his nascent idealisation of homosexual love.

In 1859 he revealed the gossip about Vaughan to a friend during

a discussion about ‘Arcadian Love’. This friend persuaded

Symonds to tell his father, Dr John Addington Symonds, who

subsequently insisted that Vaughan resign. Naturally, this

turn of events upset the young man, as he felt that he was

responsible for the headmaster’s disgrace and the ending of

his career.

Symonds then fell

in love with Willie Dyer who was a chorister at Bristol Cathedral.

He confessed this relationship to his father who rather surprisingly

was not condemnatory, but suggested that his son gradually

finish the affair. In the early ‘sixties, Symonds formed

an attachment to another chorister, Alfred Brooke: this time

he found it impossible to suppress his feelings. His health

deteriorated and he suffered from stress and nervous complaints.

The final issue

was the suggestion by a certain Dr. Spencer Wells, surgeon

to Queen Victoria’s household, that Symonds’s medical condition

was a result of his sexual repression and advised the young

man to take the ‘cure’ of marriage. He was wedded to Janet

Catherine North in early 1864, but did not attempt to change

his fundamental sexual orientation.

John Addington

Symonds first came to Malvern with his sister Charlotte on

7 April 1862 on a reading holiday. This was a popular entertainment

with Victorian intellectuals and would probably have been

combined with a walking tour in the local countryside. He

was to visit Malvern on a number of occasions not least because

his future brother-in-law, T.H. Green lived there.

It is not clear

when the poem At Malvern was written. It could have

been in 1862 when Symonds would have been 22 years old or

it could have been around 1868, some four years after he had

been married. What is clear from a close reading of the text

is that at the time of writing, the poet was struggling with

his sexuality. There is a suppressed anguish throughout the

poem- even in its ‘descriptive’ lines. An appreciation of,

and sympathy with, this mood is an integral part of Ian Venables

musical setting.

The poem as set

by the composer was printed in New and Old: A Volume of

Verse which was published in 1880. The title in that book

was changed to On the Hill-Side and was included in

a section entitled ‘Lyrics of Life and Art’. Other titles

included To One in Heaven, Two Moods of the Mind

and Love in Dreams. However, Ian Venables explained

to me that the poem was first published with the title At

Malvern in a private pamphlet entitled Crocuses and

Soldanellas. (1870)

At Malvern

is a good example of a ‘Shakespearean’ sonnet- with a couple

of twists. The formal structure of the poem consists of fourteen

lines divided into three quatrains and a final couplet. The

metre of this poem is an ‘iambic pentameter’ which means that

there are typically ten syllables in each line with the even

numbered syllables receiving the accent. The sixth line is

the exception to this having eleven, although ‘murm’ring’

can be elided. Certainly, Symonds varies the scheme allowing

an accent to appear at the start of a line –for example, the

imperative “Hush! In the thicket still the breezes blow”.

The classic sonnet rhyme scheme is preserved throughout.

In many of Shakespeare’s

sonnets the purpose of the couplet is to draw together the

threads of the poem – to provide a conclusion. Often the second,

and sometimes the third quatrain would be used to introduce

a hiatus into the flow of the poem: to complicate the train

of thought. This is known as the ‘volta.’ Symonds provided

the ‘twist’ in the second quatrain. The key phrase here is

“Deep peace is in my soul”.

At

Malvern

The

winds behind me in the thicket sigh,

The bees fly droning on laborious wing,

Pink cloudlets scarcely float across the sky,

September stillness broods o'er [everything] ev’rything.

Deep

peace is in my soul: I seem to hear

Catullus murmuring 'Let us live and love;

Suns rise and set and fill the rolling year

Which bears us deathward, therefore let us love;

Pour

forth the wine of kisses, let them flow,

And let us drink our fill before we die.'

Hush! in the thicket still the breezes blow;

Pink cloudlets sail across the [azure] sky;

The

bees warp lazily on laden wing;

Beauty and stillness brood o'er [everything] ev’rything.

The initial mood

of this poem is one of stillness, disturbed only by the sighing

of the wind in the thicket. I have noted that the original

title was On the Hillside and, although it is not certain

that this poem was written whilst Symonds was in Malvern it

would certainly give support to an image of the poet sitting

near the top of Midsummer Hill or Worcestershire Beacon. The

reader is reminded of William Langland and Piers Plowman:-

And

on a May morning on Malvern Hills,

There befell me as by magic a marvellous thing:

I was weary of wandering and went to rest

At the bottom of a broad bank by a brook's side,

And as I lay lazily looking in the water

I slipped into a slumber, it sounded so pleasant.

Certainly Symonds

suggests that it was a lazy day, perhaps recalling Matthew

Arnold’s immortal phrase “All the live murmur of a summer’s

day”. After musing on this seeming paradise, with only a gentle

nod to the approaching autumn, the poet turns to review his

life and his potentially difficult situation. Most likely

this refers to his sexual orientation but it may have been

his sense of having been bullied or his illness. It could

have been all of these.

The poet appears

to resolve his problems by claiming that “Deep peace is in

my soul...” This is the heart of the poem. Yet, no matter

how often I read these lines, the words do not seem to ring

true. I believe that he is either being ironic or else he

is furiously willing himself to be at peace. The autumnal

reflection continues with an image of “Suns rise and set and

fill the rolling year/Which bears us deathward’ which suggest

darker thoughts and a mood that was not truly relaxed on the

hillside.

The reference

to the great lyric poet Catullus and his poem ‘Come, Lesbia,

let us live and love’ surely clarifies the situation. “Therefore

let us love” becomes the essence of his solution. Symonds

wants to “…pour forth wine and kisses...” For a moment the

poet sits up, his mind clearing. It is his resolve to follow

the ancient bard’s advice- at least “to drink our fill before

we die...”

After a plea to

the poet’s soul to “Hush”...or less prosaically to the noisy

day trippers around him, the original mood of the poem returns,

as if by magic. The listener is back with the poet on the

hillside. The poem ends with the statement that “beauty and

stillness brood o’er everything.” The equilibrium of body

and soul is restored, at least for a short space.

The Catullus reference

is critical. Symonds’s rendering of ‘vivamus mea Lesbia, atque

amemus’ is quite straightforward- ‘Let us live and love’ –naturally

omitting any reference to Lesbia. This is one of Gaius

Valerius Catullus’s great poems: it is the first

referring to his muse, who is usually regarded as being Clodia

Metelli, the wife of Quintus Metellus Celer, a statesman at

the time of Pompey. The CD sleeve note suggests that by quoting

this line, Symonds was quite simply signifying ‘living life

to the full.’ Now, obviously there is something in this view,

however I believe that there is more significance to this

allusion than some kind of hedonistic desire to fill life

with pleasure. I believe that the poet asks the reader to

recall the rest of Catullus’s poem, especially the two lines

following the quotation:-

“...and

value at one farthing

all the talk of crabbed old men!”

F.W. Cornish Loeb Classical Library No.6 p. 7

The final part

of Catullus’s poem dwells on the transience of life and the

need to fit in thousands of kisses. However there is a twist

at the end of the Latin poem. The poet suggests that after

all these kisses:-

“we’ll

wipe them out, lest we know,

Or lest anyone evil can envy,

When they know how many kisses there were.”

http://everything2.com/title/Catullus%25205

There is a twofold

suggestion that what is troubling the Roman poet is a) being

found out and b) possibly less problematic, of salving his

own conscience. For Catullus, the discovery of his love for

Clodia would probably have meant his death or his exile.

For Symonds the discovery and advertisement of his homosexuality

could have meant disgrace and the closure of career paths.

This is not the place to discuss the Victorian understanding

of ‘gayness’ but it is fair to say that Symonds would have

felt a considerable sense of alienation and tension living

in a society that saw homosexuality as a disease that may

or may not be ‘curable’. It is in this context that ‘Deep

peace’ would have struggled to enter his soul at that time.

John Addington

Symonds chose the path of following his heart and campaigning

for gay liberation in Britain. He was to later write the first

modern history of male homosexuality.

I asked Ian Venables

why he chose to set this poem. His answer was two-fold. First,

and perhaps most significantly, he has devoted a considerable

effort to the rediscovery of the life and works of Symonds.

Graham J. Lloyd has written that this interest has become

one of the turning points in Venables career. He has assembled

a collection of his writings and has begun to catalogue the

poetry: some seven hundred poems exist in print or manuscript.

It was during this research that Venables discovered At

Malvern. But an additional impetus was the composer’s

love of the Malverns in particular, and the Worcestershire

countryside in general. And finally there were the considerable

literary and musical associations connected with this landscape.

One thinks of William Langland, Edward Elgar and A.E. Housman.

The poem has a considerable sense of place and history. It

is easy to think of Caractacus and then back through the ages

to Ancient Rome and the poet Catullus. The atmosphere of the

poem evokes a kind of Arthur Machen-ian slippery time.

The song is dedicated

to Marjorie Chater-Hughes. This lady, a personal friend of

the composer, was a notable ballet teacher in Malvern. She

established a ballet school there and was highly regarded

by her former pupils. She died on 6 January 2006 at the great

age of 99.

Ian Venables has

approached this difficult text with both sensitivity and technical

skill. As suggested above, the subject matter of the poem

is almost certainly a reaction to the tensions that the poet

felt about his sexuality. Yet there is much pastoral imagery

here that celebrates the beauty of the countryside and the

joy of being alive in that landscape. Any setting of a sonnet

is bound to be problematic. V.C. Clinton-Baddeley, in an essay

printed in Words for Music (CUP 1941 p.19) implies

that it is virtually impossible to set Shakespeare’s (and

by extensions anyone else’s) sonnets to music. Brian Blyth

Daubney in a British Music Society booklet about the songs

of Benjamin Burrows elaborates on this point. He suggests

that the composer will struggle with the rigid fourteen iambic

pentameters, and believes that these must “be subjected to

an infinite variety of approaches to achieve freedom from

musical monotony.” He further notes that “only when there

is a clear end of sentence or specific change of idea can

one justify an interruption of the words, and even then, some

relevant musical link must allow the poets line of thought

to be sustained.”

At Malvern

is a well structured song that certainly fulfils Daubney’s

criteria. The mood of the Venables setting is basically divided

into two major contrasting elements. Firstly there is the

meditation on the rural paradise seen from the Malverns and

secondly the struggle with the poet’s sexuality. This is presented

as a tripartite song that is some 53 bars long. The first

and final sections are written in common time and the middle

16 bars use a 4/8 time signature. There is no key signature

for this song – but there is an 'A major' feel about much

of the work. However, at the climax the song modulates to

‘five flats’.

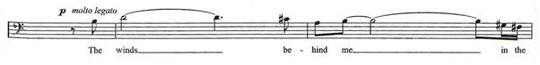

[Fig.1] © 2009

Novello & Company Limited. Reproduced with the permission

of the publisher

The accompaniment

to At Malvern is as important as the vocal line and

sets the mood of the song at the outset. The work opens with

the main piano figure [Fig.1]. This murmuring sound, which

is surely meant to reinforce the idea a perfect summer’s day,

is repeated almost identically ten times. There are only two

subtle changes here – here the B ♮

changes to a C. and the C# changes to a C♮.

These are important structural alterations.

It makes the music sound just that little bit unsettled: the

mood of ‘calm and serenity’ is disturbed.

[Fig.2] © 2009

Novello & Company Limited. Reproduced with the permission

of the publisher

The soloist virtually

creeps into this mood with a declaration that “The winds behind

me in the thicket sigh...” The composer’s use of long notes

– three or four beats for the accented words ‘winds’ ‘me’

‘thicket’ and ‘bees’ - lends to the lugubrious atmosphere

of this opening section. Yet the melody begins to become a

little more rhythmically complex once the ‘pink cloudlets

scarcely float across the sky’. At this point the vocal line

owes much to the melodic shape of the accompaniment or vice

versa. There is a considerable use of canon between the two

parts with the piano usually following a single beat behind

the tenor. Just before the second quatrain begins the accompaniment

clearly sounds the tolling ‘bell’ for the first time.

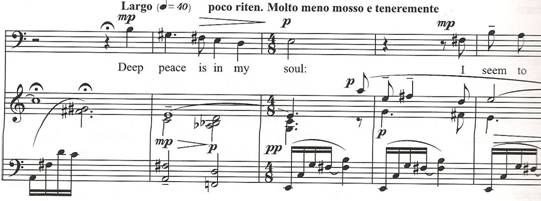

[Fig. 3] ©

2009 Novello & Company Limited. Reproduced with the permission

of the publisher

A major hiatus

occurs at the end of the 17th bar.

A descending phrase, insists

that ‘Deep peace is in my soul.’ It is a decorated E major

triad that ends quietly with a change into 4/8 time. The

second

quatrain is certainly the most involved part of this song.

The variety in the accompaniment is considerable, utilising

a series of chords including parallel thirds and fifths and

an attenuated form of the initial Fig. 1 motive. The climax

of the piece comes at the declamation of the words “Therefore

let us love” which finishes on a high F♮.

The vocal line then slowly collapses towards the sentiment

of “Pour forth the wine of kisses, let them flow, And let

us drink our fill before we die”.

A major consideration

with this section is the musical ‘word painting’: this occurs

at three important words –‘love’ ‘deathward,’ and ‘kisses’.

It is surely not a coincidence that the highest point of the

melodic phrase and the song is on the word ‘love’ with all

its power and positivity. The melodic step of a perfect fifth

on ‘downward’ and the uncomfortable dissonance supporting

it emphasises the decline to the abyss. Finally, the complex

and sensuous harmony accompanying the word ‘kisses’ lends

a sense of delicious eroticism to the moment. The composer

tells me that they all occur “quite unconsciously”.

There is a short

pause before the opening accompaniment figure returns, but

this time it is decorated with bell-like bare fifths and fourth

chords. This mood continues to the end of the song when the

poet and composer re-establish the original ‘dreamy’ mood

of the opening. However the bells cease, only to be replaced

by imitation towards the final bars. The two bar coda nods

to the start of the middle section before the work closes

with a pianissimo chord in the higher register in the piano.

The tolling bell can be heard for one last time.

At present there

is only one recording of this song available. It is on a CD

called The Songs of Ian Venables sung by the tenor Kevin McLean-Mair

and accompanied by Graham Lloyd. It is released on ENIGMA

Digital ED 10045.

John France

July 2009 ©

With many

thanks to Ian Venables for encouragement, advice and for arranging

with Novello for use of the musical extracts.

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews