|

|

|

Not available in the USA.

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

|

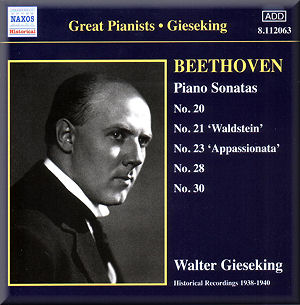

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 20 in G major, Op. 49/2 (1796) [06:34]

Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53, “Waldstein” (1804) [18:41]

Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, “Appassionata” (1805) [21:46]

Piano Sonata No. 28 in A major, Op.101 (1816) [15:58]

Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109 (1820) [15:48]

Walter Gieseking (piano)

Walter Gieseking (piano)

rec. 1940, Berlin (Op. 49/2); Berlin, 11 August 1938 (Op. 53); New

York, February 1939 (Op. 57); New York, 24 February 1939 (Op. 101);

Berlin, Spring 1940 (Op. 109)

NAXOS 8.112063 [78:48]

NAXOS 8.112063 [78:48]

|

|

|

I’ve never quite been able to share the enthusiasm for historical

recordings. To my ears, the perceived “truth” of the performances

– a dubious concept in any event: the view that few performers

today can stand comparison with the finest of the past is quite

false – is too often compromised by execrable sound. But Walter

Gieseking has long been one of my favourite pianists in the

music of Debussy, so I was intrigued to know how I would feel

about his Beethoven playing. The result is a triumph.

I was most apprehensive about the sound, so let me begin with

that. My technical knowledge of recorded sound restoration is

virtually nil, and I haven’t heard these performances in any

other transfers. These two factors should be taken into account

when I say that it seems to me that Ward Marston has worked

miracles with these recordings. Background hiss is fairly high,

but it has been most sensitively dealt with, fading in and out,

for example; also, it is maintained between movements so as

not to break the atmosphere, a nice touch. In short, whilst

you never forget you are listening to 78 rpm records, you are

conscious that they are in pristine condition and that they

are not going to wear out! The piano sound itself is clean and

immediate, and is that the pianist himself humming or groaning

here and there? All this helps the listener concentrate on the

music and the playing and (almost) to forget about the sound.

One of the first things that strikes the listener about the

playing in the two named sonatas is the tempo. Gieseking plays

the first movement of the Waldstein at a cracking pace:

Allegro con brio is what Beethoven marked, and brio

there is in plenty. He is consistently faster than Schnabel

(also on Naxos) in the faster movements of both sonatas, and

significantly faster than Ingrid Fliter, for example, in her

superb performance of the Appassionata on EMI. He occasionally

comes adrift in rapid semiquaver runs – his fingers running

away with him – but this only underlines the individuality and

humanity of the playing. These fast passages are often accompanied

by a certain wildness of expression. The episodes in the rondo

finale of the Waldstein are a case in point, as is

the closing passage of the Appassionata, where the

playing seems almost possessed.

In spite of this, and remembering other passages of quite extraordinary

power, this is far from a barnstorming view of Beethoven. On

the other hand, to say that the playing is characterised by

restraint would not be true either. No, it is more complex than

that. Some, I feel sure, will find the emotional temperature

on the cool side. This comes out particularly in the two late

sonatas, those that precede and follow the mighty Hammerklavier.

The Op. 101 sonata is a strange work indeed, complete in itself,

a perfect work of art, yet strangely transitional in nature.

Its first movement ambles along beautifully in this performance,

but the pianist seems anxious not to put himself between the

composer and the listener. To say the effect is flat would be

to criticise, to say the pianist “could do better”. I prefer

to describe the effect as rather muted – though even that word

is too strong and too heavily loaded with value judgement –

the result of Gieseking trusting the composer and presenting

the notes, as it were, unadorned. The finale, too, an early

manifestation of Beethoven’s preoccupation with fugal writing,

is driving and muscular, but without any overt search for shallow,

surface drama. Perhaps Gieseking was an early period performer.

There is certainly a classical sensibility about much of the

playing here, and which is evident above all in the clarity

of passagework and texture.

Gieseking takes all the repeats in the Appassionata,

including the long one in the finale. You don’t get the exposition

repeat in the little G major sonata though, nor in the Waldstein,

which is more of a pity. There are missing repeats, too, in

Op. 101. The booklet carries an interesting essay on the pianist

and on these performances by Jonathan Summers.

Just as Paul Lewis is different from Alfred Brendel in Beethoven,

and just as Schnabel is different from both of these, so is

Walter Gieseking his own man in this repertoire. Do listen to

these performances. They are not mainstream, but they are very

satisfying indeed.

William Hedley

see also review by Christopher

Howell

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews