|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

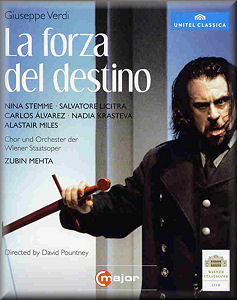

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

La forza del destino - Melodramma in four acts.

Revised 1869 version

Marquis of Calatrava, Alastair Miles (bass); Donna Leonora, his

daughter - Nina Stemme (soprano); Curra, her chambermaid - Elisabeta

Marin (soprano); Don Alvaro, lover of Leonora and of Royal Inca

Indian descent - Salvatore Licitra (tenor); Don Carlo of Vargas,

Leonora’s brother - Carlos Alvarez (baritone); Preziosilla, a gypsy

girl - Nadia Krasteva (mezzo); Fra Melitone, a Friar – Tiziano Bracci

(bass); Padre Guardiano, Father Superior - Alastair Miles (bass);

Mastro Trabuco, muleteer - Michael Roider (tenor); An Alcade, a

mayor – Dan Paul Dumetrescu (tenor); Spanish military surgeon, Clemens

Unterreiner (tenor)

Marquis of Calatrava, Alastair Miles (bass); Donna Leonora, his

daughter - Nina Stemme (soprano); Curra, her chambermaid - Elisabeta

Marin (soprano); Don Alvaro, lover of Leonora and of Royal Inca

Indian descent - Salvatore Licitra (tenor); Don Carlo of Vargas,

Leonora’s brother - Carlos Alvarez (baritone); Preziosilla, a gypsy

girl - Nadia Krasteva (mezzo); Fra Melitone, a Friar – Tiziano Bracci

(bass); Padre Guardiano, Father Superior - Alastair Miles (bass);

Mastro Trabuco, muleteer - Michael Roider (tenor); An Alcade, a

mayor – Dan Paul Dumetrescu (tenor); Spanish military surgeon, Clemens

Unterreiner (tenor)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Vienna State Opera/Zubin Mehta

Director: David Pountney

Set and Costume design: Roy Hudson

rec. live, Vienna State Opera, 1 March 2008

Picture format: 16:9, HD 1080i. Sound: dts Master Audio 5.0, PCM

Stereo. Region: 0 (worldwide)

Subtitles in Italian (original language), English, German, French,

Spanish, Chinese, Korean

Booklet English, German, French

UNITEL CLASSICA/C MAJOR

UNITEL CLASSICA/C MAJOR  708204 [161:00]

708204 [161:00]

|

|

|

Verdi wrote La forza del destino after a two year

gap from composition following the premiere of Un Ballo

in Maschera on 17 February 1859. During that period he

had become a Deputy in the first parliament of the recently

unified Italy. However, he was tiring of that scene when approached

for a new opera from the Imperial Italian Theatre in St. Petersburg.

With the composer away on Parliamentary business his wife, Giuseppina,

handled the correspondence and persuaded Verdi that with suitable

provisions the cold in Russia would be manageable and that he

should accept the highly lucrative commission. The first suggestion

of subject, Victor Hugo’s dramatic poem Ruy Blas with

its romantic liaisons across the social divide, met censorship

problems. After some struggle for another subject Verdi settled

on the Spanish drama Don Alvaro, o La fuerza de sino

by Angel Perez de Saavedra, Duke of Rivas. This was deemed suitable

in Russia and Verdi asked his long-time collaborator Piave to

provide the libretto. Verdi worked throughout the summer of

1860 as Giuseppina made the domestic arrangements for the shipment

of Bordeaux wine, champagne, rice, macaroni cheese and salami

for themselves and two servants. The Verdis arrived in St. Petersburg

in November 1861, but during rehearsals the principal soprano

became ill. As there was no possible substitute the premiere

was postponed until the following autumn and after some sightseeing

the Verdis returned home. At its delayed premiere on 10 November

1862 the work was well received with the Czar attending a performance.

Opera Rara has issued a sound recording of this original version

(see review)

and a DVD exists, recorded in St Petersburg in 1998, in a reconstruction

of the 1862 sets (Arthaus Music 100 078).

The original version was reprised in St Petersburg in the two

seasons following its premiere and was seen in several Italian

cities in 1863 as well as in Madrid in 1864 and Vienna in 1865.

Verdi withheld the score from theatres that he considered incapable

of doing it justice. It is evident that he recognised the need

for alterations early on when he transposed the tenor aria in

act 3 downward on the basis that only Tamberlick was capable

of meeting its demands. He instructed his publisher, Ricordi,

to include the alteration in the scores he hired out. Verdi

was also unhappy with some other aspects of the score as it

stood, particularly the three violent deaths in the final scene.

However, it was not until Tito Ricordi proposed a revival for

the 1869 La Scala carnival season that Verdi found a way forward.

By then Piave, the original librettist had suffered a stroke

that paralysed him for the last eight years of his life and

during which Verdi provided much financial help to his family.

The task of versifying the revisions fell to Antonio Ghislanzoni

who the composer had met at the time of the writing of Attila

and with whom he developed a cordial relationship.

The revised La Forza del Destino was premiered at La

Scala on 27 February 1869. The presentation marked a rapprochement

between Verdi and the theatre that he had barred from premieres

of his works for over twenty years. The revisions of the score

from the original version are significant rather than major

and involve the substitution of the prelude by a full overture,

which nowadays is often played as a concert piece. A major revision

of the end of act three includes the removal of the demanding

tenor double aria whilst the whole final scene is amended to

avoid the triple deaths. It is replaced by the Father Guardian’s

benediction as Leonora dies and Alvaro is left alive (CH.45).

In La forza del destino Verdi writes on a massive dramatic

canvas. He described the story as powerful, singular and

truly vast (The Operas of Verdi. Budden. Cassell. Vol 2

p.430 et seq). Some cynics have described it as a rambling

story of improbabilities and contend that it is Verdi’s darkest

opera. It is certainly a story of unrequited love, racial prejudice

and violent deaths. Ever the man of the theatre Verdi leavened

the dark facets of the story with brighter, even humorous, interludes.

The first, in act 2, (CHs.7-13) is set at an inn where Preziosilla,

a gypsy woman of easy virtue, is recruiting for the army promising

fame and fortune as well as sexual favours. The scene is an

ideal counterweight to the accidental death of Leonora’s father

at her suitor’s hand in the first act. Further leavening, even

humour, comes with the character of the irascible monk Melitone

who berates the peasants as he distributes charity (CH. 39)

or laments the goings-on in the army camp as he is forced to

join a whirling dance with the vivandiers in act 3 (CH.35).

Verdi poured great intensity and creativity into this work and

the opera contains an overture, scenes, arias and duets that

are amongst his finest music. The long melodic cantilena of

the meeting between Leonore and Padre Giordano in act 2 scene

2, that starts with Leonore’s aria Sono giunta and

concludes with the trio with chorus of La Vergine degli

Angeli (CHs.14-21) as she is granted sanctity have, I suggest,

no parallel in Italian opera since Bellini’s Norma

in 1833. Further, none of comparable length and dramatic intensity

are found elsewhere in Verdi’s work.

Given the nature of this work from his mature period it is incumbent

on the producer and set designer to clarify the complexities

so as to assist the audience, or viewer, to relate the complexities

and relationships of the various scenes. It is with regret that

I state that the team here manifestly fail in this respect.

The failure starts with setting the costumes in the present

day. The Father Guardian of the Monastery goes around in a suit

and without a tie, belying his status and station. Preziosilla

arrives in a red Wild West costume and hat, her friends likewise,

and in Hot Pants. The odd drape of a cloak or cassock does little

to clarify the religious moments of offering sanctity. The sparse

staging of the opening act, a single metal-framed bed, is later

contrasted with a meaningless large piece of revolving metal

scaffolding that reminds me of the gasometer that marked the

entrance to my nearest city for many a year. Add projections

during the battle scenes, a hardly recognisable entrance to

the Monastery along with the idiosyncratic costumes and many

will be confused as to what is going on and why.

Verdi always wrote with singers, general and often specific,

in mind. For this dramatic opera he wanted spinto-sized

voices. I have already indicated that he watered down the vocal

demands on the tenor singing Alvaro for the 1869 version. It

still demands substantial vocal weight but also, as Bergonzi

demonstrates so superbly on the 1969 EMI audio recording under

Gardelli (7 64646 2), considerable vocal nuance. In this performance

the Sicilian Salvatore Licitra has the necessary heft, but a

complete lack of vocal taste or sensitivity. He slides up to

notes and simply belts out the words seemingly without making

any effort whatsoever at vocal nuance, colour or expression.

With dryness at the top of his voice it’s not even viscerally

exciting as it used to be with the likes of fellow Italians

Del Monaco or Franco Corelli. In contrast, Alvaro’s implacable

pursuer, Don Carlo, brother of Lenora, sung by Carlos Alvarez

has the ideal variety of tone allied to strength of voice, awareness

of characterisation and expressiveness. He makes a near ideal

interpreter of this demanding role. In an era when the shortage

of genuine Italianate Verdi baritones is so acute his presence

and contribution is particularly welcome as is his frightening

histrionic intensity in portraying Don Carlo’s implacable intention

to find his sister and her lover. As his sister Leonora, loved

by Alvaro, Nina Stemme sings with strong bright, forward lyric

tone. She sings the long expressive melodic line of Leonora’s

Pace, Pace, mio Dio (CH.43) in the final scene as well

as I have heard it since Leontyne Price on her mid-1970s audio

recording under Levine (RCA) and surpassing the great American

in her later, and last, performances of the role as caught on

DVD in 1984 (see review).

Elsewhere, she characterises well in her acting and brings welcome

nuance to the meaning of the words. In characterisation, along

with pleasing tone and expression, she is matched by Nadia Krasteva

who conveys a vivacious Preziosilla whose Rataplan

(CH.38), by then she is also kitted in Hot Pants, goes with

a bang in more ways than one.

As the Father Guardian Alastair Miles’ bass is as lean as his

figure. His voice has always been a true bass, but lacking in

sonority and none more so than in this role where his tone shows

sure signs of drying with age. The combination of his vocal

characteristics and costume fail to bring out the humanity that

Verdi invests in his music. It is the same with Tiziano Bracci

as Melitone. Some have suggested this character was a part-model

for his Falstaff. This Melitone, also suffering dryness of tone,

manages to miss any humour which is evident in other recordings,

visual and audio.

Where Pountney does score over the best sung recent video recording,

from Florence in 2007 and reviewed

by a colleague, is in his detailed management of the chorus

who are always actively involved although the purpose is sometimes

unclear. Zubin Mehta conducts both versions. He lets Verdi’s

melodic lines speak for themselves and the drama unfolds naturally.

The Vienna Staatsoper audience are on best behaviour,

or confused, but let the opera proceed without excessive and

lengthy interruptions as was at one time their habit.

Robert J Farr

see also review of the DVD release by David

Bennett

|

|