|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Mass in C, K 317, Coronation (1779) [24:48]

Ave verum corpus, K618 (1791) [3:12]

Vesperae solennes de Confessore, K339 (1780) [26:52]

Laurence Kilsby (treble); Jeremy Kenyon (alto); Christopher Watson

(tenor); Christopher Borrett (bass)

Laurence Kilsby (treble); Jeremy Kenyon (alto); Christopher Watson

(tenor); Christopher Borrett (bass)

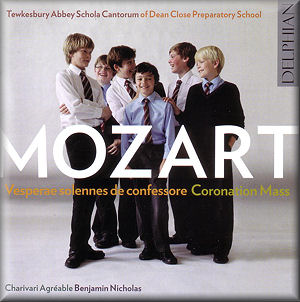

Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum of Dean Close Preparatory School

Charivari Agréable/Benjamin Nicholas

rec. 12-13 July 2011, Merton College Chapel, Oxford

Texts and translations included

DELPHIAN DCD34102 [54:59]

DELPHIAN DCD34102 [54:59]

|

|

|

Thirty-two singers are listed in the booklet accompanying this

disc, of whom eighteen are trebles. They are pupils at Dean

Close Preparatory School in Cheltenham, and they join with the

adults to sing the weekday evensong services at Tewksbury Abbey.

Charivari Agréable are a period instrument group based in Oxford.

A little more than a year separates the composition of the two

principal works on this disc. Mozart’s early life is dominated

by travelling, but these works were composed during a two-year

period when the composer was in Salzburg in service to the Archbishop,

a situation he found increasingly frustrating. The short, celebrated

Ave verum corpus was composed in the very last year

of his life when he was visiting his wife and son who were staying

in the spa town of Baden.

The performance of the Mass is an exuberant one. The energy

level rarely dips in this work, and these performers respond

with enthusiasm. There seems no question that the young singers

are thoroughly enjoying themselves, but I think rather more

in the way of variety of dynamics should have been expected

of them. Mozart is either forte or piano,

but forte is at least that here, and often rather more,

whereas indications of piano are not always respected

to the letter. I felt this particularly at the opening of the

Sanctus, where the forthright attack is rather unwelcome after

the rather relentless Credo. It is all superbly sung, though,

and if you like your Mozart like this, and the idea of an all-male

choir appeals, there is certainly no reason to hesitate.

Careful control of pace and phrasing is necessary if Ave

verum corpus is not to become marmoreal. This performance

is again beautifully sung and manages to stay on the right side

of the line. I can’t in all honesty say the same about the famous

“Laudate Dominum” in the K339 Vespers, as the tempo is really

too slow and the phrasing rather too affectionate, with something

of a tendency to hold back at the ends of phrases. This is the

moment, however, to draw attention to the remarkable treble

soloist, Laurence Kilsby. He has a beautiful voice and his singing

is highly expressive and musical. One notes, too, especially

in the “Laudate Dominum”, his outstanding breath control. Something

of a pity, then, that he sings with quite a pronounced vibrato

when there is not of trace of this in the introductory violin

melody. The remaining, adult, soloists are very fine too, though

vibrato remains a problem, if only because of the discrepancy

in style between the vocal participants and the instrumental

ensemble. (I have no problem, personally, with vibrato in Mozart.)

Otherwise, the performance of the Vespers follows pretty much

the same pattern as that of the Mass, with both its strong points

and its weaker ones. There really is more light and shade in

Mozart’s choral writing than is in evidence here, and the effect

sometimes becomes tiring. The recording is very immediate and

vivid, with the quartet of soloists well forward, which rather

exacerbates this. But there are many wonderful moments. These

performers’ way with the word “saeculorum”, for example, just

before the final “Amens” of the second movement “Confitebor”,

is only one example of singing that it quite seductive and totally

convincing. Overall, though, the singing has a few rough edges

compared to that of the Mass, unsurprising as it is a more difficult

work.

Benjamin Nicholas is Director of Choral Music at Dean Close

Preparatory School, and keen-eyed readers will spot that he

is also jointly responsible, with Peter Phillips, for the outstandingly

fine choir at Merton College, Oxford, whose first recording,

entitled “In the Beginning”, was recently released, also on

Delphian. Charivari Agréable play splendidly, and seem at one

with the conductor’s view of the works.

William Hedley

see also review by John

Quinn

|

|