|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

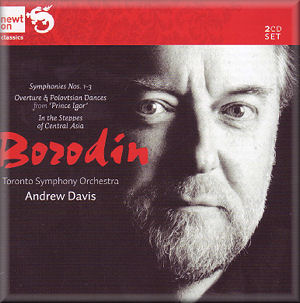

Alexander BORODIN (1833 - 1887)

Symphony No. 1 (1862-67) [34:42]

Symphony No. 2 (1869-76) [26:23]

Symphony No. 3 (1882) [17:43]

String Quartet No. 2 in D - Notturno [8:41]

In the Steppes of Central Asia (1880) [7:23]

Prince Igor (1869-87): Overture [10:32]; Polovtsian

Dances [12:58]

Toronto Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Davis; New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein (Asia); St Petersburg Camerata (Notturno)

Toronto Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Davis; New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein (Asia); St Petersburg Camerata (Notturno)

rec. Massey Hall, Toronto, 1976 (Davis); Philharmonic Hall, New York, December 1969 (Bernstein); Radio House, St Petersburg, June 1993 (Notturno) ADD, DDD (only Notturno)

NEWTON CLASSICS 8802097 [77:34 + 57:17]

NEWTON CLASSICS 8802097 [77:34 + 57:17]

|

|

|

Borodin was only a part-time composer - he was a full-time professor

of chemistry - and his original orchestral works fit easily

onto this pair of discs. Indeed when he died his music was in

such disarray that it required a considerable amount of editorial

work by Glazunov and Rimsky-Korsakov to put it into a performable

state.

Of the works the composer did manage to complete, the First

Symphony is frankly an experimental work which does not

always ‘come off’; and the Third Symphony is a torso

left incomplete at his death which Glazunov had to reconstruct.

The resulting pair of movements sound like intermezzi, and one

feels that the work needs more substantial movements to be a

really satisfactory whole.

The real masterwork which Borodin left, however, is undoubtedly

the Second Symphony: one of the greatest Russian symphonies

of the nineteenth century and worthy to be ranked with the last

three of Tchaikovsky. In particular the slow movement is a beautiful

piece which looks forward to Rachmaninov, especially in the

return of the main theme on massed strings. But the symphony

presents major problems for performers, and one of these comes

with the initial statement of this main theme on solo horn.

This opens with a single detached note which if not very tactfully

handled can easily sound like a false entry. There is a particularly

awful example in the recording by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra

under Svetlanov,

and Carlos Kleiber in Stuttgart is nearly as bad. It needs to

be carefully integrated with the opening phrase. Davis’s Toronto

player here totally ignores the detached note and blends it

into the melody, which is not what Borodin wrote, and his playing

thereafter is sometimes inelegant.

The main problem with the Davis performances, which constitute

the greater part of the contents of this two-disc set, is the

recorded balance. When the recordings were issued in the late

1970s - the disc cover states that the recording date for the

symphonies is unknown, but it was 1976 - the set came into competition

with contemporaneous recordings under Tjeknavorian,

and it has to be admitted that despite the controversially wayward

interpretations of the Armenian conductor listening to the recordings

again confirms their superiority. The balance in Toronto is

horribly forward and exposes the slightest defect in the orchestral

playing, which is not impeccable. In the Polovtsian Dances

there is an unnamed and un-credited chorus employed, but the

very forward balance they are given cannot disguise their woeful

inadequacy in numbers; the tenors sound horribly strained.

Davis for some reason never recorded In the steppes of Central

Asia as part of his otherwise complete survey of Borodin’s

orchestral music, and a 1969 performance by Bernstein is therefore

interpolated. Sadly, the recorded balance here is, if anything,

even worse. The idea behind the music is straightforward enough;

the travelling caravan should advance towards the listener and

then retreat into the distance. Here the woodwind and high violins

at the beginning are already right in the listener’s face, and

then as the music grows louder the orchestra paradoxically enough

recedes into the middle distance – only for the process to be

reversed at the end. There is therefore no light and shade,

no sense of progress. To add insult to injury, the melody in

the winds at the climax is all but drowned out by the overly

forward balance given to the strings and brass. This is most

certainly not one of Bernstein’s great recordings, although

he paces the music well.

The most interesting item in this collection is one of the shortest

tracks - and the only digital recording - an orchestration of

the Nocturne third movement of the Second String

Quartet. There is no indication of who was responsible

for the orchestral arrangement. David Gutman - who contributes

a new and commendably informative set of notes - seems unsure.

He refers to the arrangements by Sargent for strings and Rimsky-Korsakov

for violin solo and small orchestra - it is clearly neither

of these - and also to an arrangement by Nicholas Tcherepnin

which this appears to be. Järvi includes this arrangement in

his Borodin collection; and it is very effective. It clearly

expects a large romantic orchestra with plenty of romantic violin

‘wash’, and this is not what it receives here from the St Petersburg

Camerata, who appear to have no more than two desks of strings

in any section. One other minor point: the muted horn solo towards

the end is played with what sounds like hand-stopping, and the

resulting brassy rasp sticks out unpleasantly like a sore thumb.

The performance otherwise is very good and nicely inflected,

although no conductor is credited at all.

This one track of interest is not sufficient to commend this

reissue. There any many other recordings of these works, and

many better ones at that.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

See also review by Rob

Barnett

|

|