|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

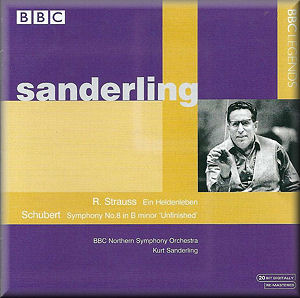

Richard STRAUSS (1864-1949)

Ein Heldenleben, op. 40 (1897-1898) [42:48]

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Symphony no.8 in B minor, D759 Unfinished (1822) [27:19]

Barry Griffiths (solo violin)

Barry Griffiths (solo violin)

BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra/Kurt Sanderling

rec. Free Trade Hall, Manchester, 30 September 1975 (Strauss); BBC studios, Manchester, 17 April 1978 (Schubert)

BBC LEGENDS BBCL 4262-2 [70:25]

BBC LEGENDS BBCL 4262-2 [70:25]

|

|

|

Ein Heldenleben is all too often a piece for show-offs.

Orchestras glory in demonstrating their virtuosity – and the

sheer noise that they can make – while sound engineers have

a real field day displaying what they and their technology can

do. Meanwhile, egocentric conductors can picture themselves

as the heroic central focus of Strauss’s musical canvas: Herbert

von Karajan did so quite literally, of course, in 1974 when

he was notoriously depicted on the cover of his new EMI recording

dressed as what appeared to be a leather-coated Aryan Übermensch

lit as if for a Nuremburg rally - though, in his definitive

Karajan biography, Richard Osborne notes that “a charitable

view of this portrait would be that it makes him look like superannuated

biker, albeit an extremely well preserved one.” It is, in such

circumstances, all too easy to overlook the music itself or

to take it for granted as simply a vehicle used by musicians

for their own purposes.

I have listened to Strauss’s tone poem many times in

the past few years, but this enthralling resurrected account

from Kurt Sanderling and a BBC regional orchestra is a rare

occasion where I can also say that I heard it. Set down

in 1975, it is an example of pure – though certainly not simple

– music-making that pays the composer the compliment of taking

the piece seriously.

Kurt Sanderling – a most affable man, by all accounts, who has

just passed away at the grand old age of 98 - spent a large

proportion of his working life behind the Iron Curtain. From

the 1970s onwards, however, he was increasingly allowed to travel

internationally and, as we can see on this disc, did not confine

himself to capital cities and metropolitan orchestras.

Make no mistake, however: the 1975 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra

(to be renamed the BBC Philharmonic seven years later) was a

band that it was, if this performance is a guide, well worth

travelling – or at least tuning in to BBC Radio 3 – in order

to hear. David Patmore’s useful booklet notes quote its then

leader Barry Griffiths as saying that Sanderling “gave us the

impression that he thought we were a great orchestra and as

a result he got the absolute most out of us”, and it is hard,

listening to the results on this disc, to disagree with that

assessment of the outcome. Mr Griffiths himself, for one, gives

an outstandingly moving performance of the solo violin part

– the first time, it seems, that he had played it in public:

it is thus a pretty poor show that the Medici Arts proofreaders

seem unsure whether his surname is “Griffiths” or “Griffith”.

This is, generally speaking, an account that plays down some

of the score’s surface overkill in favour of a more contemplative

and sensitive approach. That is not, however, to say that Sanderling’s

tempi are especially slow. Indeed, looking at the versions on

my own shelves I see that, in bringing in the work at 42:48,

he outpaces such luminaries as Reiner/1954 (43:28), Beecham/1948

(43:29), Solti/1978 (44:03), Kempe/1974 (44:12), Karajan/1959

(45:39), Böhm/1957 (45:42) and Karajan/1986 (46:47). He is only

pipped at the post by accounts from an older generation of conductors

who seem to have been following an earlier and somewhat sprightlier

performing tradition - Mengelberg/1941 (42:10), Toscanini/1941

(41:55), Monteux/1947 (41:46) and - the earliest “classic” account

that we have – Mengelberg, the work’s original dedicatee, conducting

the New York Philharmonic in 1928 and bringing Ein Heldenleben

to a close in just 41:20.

The opening of Sanderling’s recording sets a high standard with

rich, full strings pulsating along in a suitably refulgent but

warm acoustic setting. It is clear that the orchestral forces

have been balanced with great care and skill and the ear catches

more detail than is often the case. The tone is darkened effectively

in The hero’s adversaries and the BBCNSO’s characterful

woodwinds demonstrate their considerable abilities. The hero’s

companion puts Barry Griffiths in the spotlight – though

he is perfectly balanced against the orchestra – and, as already

noted, he rises to the challenge with apparently great confidence

and considerable élan. This is an account of the solo

part where such considerable tension is generated that, no matter

how well you know it, each successive musical phrase seems to

bring with it some new insight. The orchestra rises to the occasion

too, producing some lush waves of sound that, while not perhaps

rivalling the Berlin or Vienna Philharmonics in depth, are intensely

involving.

Strauss’s military forces in The hero’s deeds of war are

kept under tighter rein here than is often the case. Sanderling

ensures that we hear all the thematic strands clearly and holds

his full forces in reserve until we reach the appropriate musical

point, creating a real and genuinely justified emotional resolution

to the “conflict”. More exceptionally fine playing showcased

within a carefully controlled dynamic range characterises The

hero’s works of peace and leads us into a particularly effective

The hero’s retirement from the world and the fulfilment of

his life. Taken a little more deliberately than in many

other recordings, and again notable for the particular sensitivity

of Barry Griffiths’ solo contribution, this is an utterly beautiful

account where tension and lyricism are exquisitely balanced

to achieve another perfect emotional resolution. It is unfortunately

that the cathartic effect was entirely lost on one thoughtless

oaf in the audience who destroys the elegiac mood completely

with inappropriately timed applause, but the thunderous appreciation

of his fellow concertgoers is certainly fully justified.

The Strauss is coupled on this disc with Sanderling’s only extant

recording of Schubert’s Unfinished. This is once again

an account to be treasured. The key features in Sanderling’s

approach are, as indicated in the booklet notes, concentration

and intensity, qualities he clearly imparted to the orchestra.

Once again, the BBCNSO is beautifully balanced and the wide

dynamic range that the conductor successfully creates gives

new colours and new life to the music. The emphasis is again

on balancing Schubert’s lyricism with carefully controlled tension

and drama and that aim is fully achieved. Just as with Ein

Heldenleben, this account had me listening to the score

with an unexpected level of attention and fresh ears.

If you look at our MusicWeb Bulletin Board, you will, incidentally,

find an interesting thread entitled Greatest conductor. Over

almost 3½ years it generated quite a heated exchange of views,

a few of them quite eccentric: Zubin Mehta as the greatest living

conductor? Nevertheless, having heard this BBC Legends disc

I can now begin to see where the final (to date) contributor,

a certain José Schneider, was coming from when he wrote as follows:

“I had the luck to see (hear) Kurt Sanderling conducting Brahms

and Shostakovich in his late eighties, shortly before retiring,

in Madrid of all places (our shabby National Orchestra, which

is quoted by Kondrashin in his memoirs as the worst he ever

conducted, suddenly sounded like the Berlin Philharmonic, or

the likes). Well, the only thing I can say is that I have tried

to buy all available records by him since, and I have not been

let down once!”

Rob Maynard

Masterwork Index: Ein

Heldenleben

|

|