|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

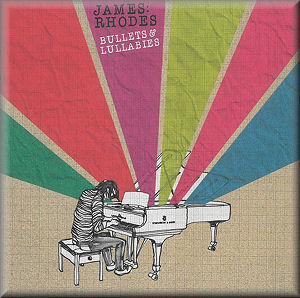

Bullets and Lullabies

CD1

Maurice RAVEL (1875-1937)

Toccata, from Le tombeau de Couperin [4:00]

Moritz MOSZKOWSKI (1854-1925)

Etude in F, Op 72 No 6 [1:37]

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Sonata in E flat, Op 31 No 3, II. Scherzo [5:19]

Frédéric CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Sonata No 3 in B minor, Op 58, IV. Presto [5:22]

Edvard GRIEG (1843-1907)

In the Hall of the Mountain King (arr. Grigory Ginzburg) [2:13]

Charles-Valentin ALKAN (1813-1888)

Grande sonate, Op 33, ‘Les quatre ages,’ I. 20 ans [6:03]

Felix BLUMENFELD (1863-1931)

Etude for the left hand, Op 36 [5:01]

CD 2

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Prelude in G flat, Op 23 No 10 [4:16]

Claude DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

La plus que Lente [5:32]

Edvard GRIEG

Berceuse, Op 38 No 1 [3:10]

Chopin

Piano Concerto No 1 in E minor, II. Romanza (arr. Balakirev)

[10:21]

Maurice RAVEL

Pavane pour une infante défunte [7:53]

Claude DEBUSSY

Clair de lune [5:58]

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Intermezzo in E flat, Op 117 No 1 [6:43]

James Rhodes (piano)

James Rhodes (piano)

rec. August 2010, Potton Hall, Suffolk, England

WARNER BROTHERS RECORD 50524 98358328 [29:33 + 43:49]

WARNER BROTHERS RECORD 50524 98358328 [29:33 + 43:49]

|

|

|

Now here’s a recital idea which works even better in practice

than it does on paper. James Rhodes’ “Bullets and Lullabies”

divides one full 75-minute program into two discs (sold for

the price of one), the bullets fast, virtuosic, and energetic,

the lullabies soft and reflective. A whole CD of quiet, calm

piano music appeals to me — last year I made Edward Rosser’s

“Visions of Beyond” a Recording of the Year — but I was afraid

that a disc of “bullets” would simply wear out my ears.

Not so, because the secret behind James Rhodes’ edgy public

persona is that he is an intelligent, sensitive, old-fashioned

(in the good, romantic sense) pianist, with a real genius for

putting together a program. Truth be told, the “Bullets” have

a lot of the lullaby in them, and the “Lullabies” are not devoid

of charge.

A cursory look at the track-list reveals Rhodes’ bullets are

not the ordinary pianist’s weapons of choice. Where is Chopin’s

Revolutionary Étude? Not here - thank goodness; I’m sick of

it. Where is Rachmaninov’s prelude in C sharp minor? - ditto.

No, here we have Ravel instead of Prokofiev, Alkan instead of

Liszt, Blumenfeld instead of Godowsky. What a difference it

makes! Rhodes tackles the Ravel toccata from Le tombeau de

Couperin with wit and fleet fingers; the Moszkowski étude

is similarly well-treated. The Beethoven and Chopin sonata excerpts

- which fit very well in the program - won’t beat all of the

dozens of pianists who have distinguished themselves here, but

they do feel admirably natural in this recital context. Moreover,

Rhodes cheerily plays up the poetry rather than the virtuoso

heft. The only “bullety” thing here, really, is Ginzburg’s volcanic

transcription of “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” played

right on the edge of sanity, the tempo lurching forward from

a slow start like a demonic music-box being wound up.

The last two selections sum up the combination of poetry and

power: the first movement from Alkan’s sonata “Les quatre ages,”

depicting the life of a twenty-something, and Felix Blumenfeld’s

étude for left hand, op 36. In his smart, witty liner-notes,

Rhodes compares the Alkan to getting out of the bed in the morning,

which seems apt: pepped up and slightly askew at first, like

a man trying to find and silence his alarm clock, its musical

ideas begin to swim together until the rousing final minute

suggests our protagonist is ready to stomp out the door and

seize the day. It’s refreshing to hear this rare music, and

Rhodes’ playing is powerful and crystal-clear. The Blumenfeld

is here because it’s spectacularly difficult to play; the CD

also comes with a video of Rhodes playing a few bars, “in case

you’re wondering if I cheated”. In truth, though, it’s a lullaby,

hypnotically gorgeous, with a sort of warm evening glow. This

is my favorite performance of the set.

Not surprisingly, then, the “Lullabies” CD strays into bullet

territory occasionally. The Rachmaninov prelude, Op 23 No 10

in G flat, opens with a dreamlike evocation of bells but the

central climax is hard-hitting indeed. Ravel’s Pavane pour

une infante défunte has rather more backbone than usual,

and an emphatic final chord — not necessarily my cup of tea.

The Grieg Berceuse isn’t quite in the same mystic world

as, say, Håkon Austbø, either, though it’s lovely.

On the other hand, the Chopin concerto movement, in a rare arrangement

by Balakirev, floats along with feather-lightness, as does Debussy’s

glowing La plus que Lente - in which Rhodes wants us

to hear jazz, and we do - and Clair de lune, at six minutes

exactly the luxurious slow tempo I like. And Rhodes has again

saved the best for very last: a luminous Brahms intermezzo,

consoling, softly reassuring, like returning home after a long

time gone. Hey, this is the end of the “PM” side of the CD.

Call that clever programming.

A word about James Rhodes himself. A lot of artists rise to

prominence on the basis of a really compelling life story —

say, Lang Lang. Rhodes’ is his struggle with mental problems

(in one newspaper story, he says he “spent nine months trying

my level best to kill myself”) and other distractions (this

disc’s liner notes say the “album could have just have easily

been called ‘Cocaine and Benzos’”), and the way in which music

rescued him from the depths. He’s fond of calling Beethoven

his drug.

Yet James Rhodes’ secret is that he’s really very good at this.

Without the backstory, he’d be a talented pianist who chooses

his music wisely, plays with clarity, indulges romantic repertoire

with a broad, loving rubato, and has a phenomenal gift for explaining

music in understandable language. The videos on the CD, of Rhodes

breaking down the things he loves about each track, are simply

marvelous. With the backstory, he’s a star. “Bullets and Lullabies”

isn’t an indulgent pop-classic album: no, the music chosen is

too good, the bullets are too poetic, the lullabies are too

subtle, the program is too off-the-beaten-track, the playing

is too mature for that. Even the liner-notes make it clear that

Rhodes would rather crack a joke than take himself too seriously.

In short, I really hope this album sells like hotcakes for Warner

Brothers Records. Maybe this is the beginning of “popular classical”

done right: a modest, even self-deprecating public persona,

clear and natural communication with the audience, music choices

that speak of the curator’s personality rather than his pandering,

an edgy, daring image — oh, yes, and fine playing, too.

In January, Rhodes told the Guardian, “I’m a big fan

of keeping the music serious but making the rest of it accessible.

How much nicer would it be if you, the pianist, provided the

programme notes? So you are talking about the composer before

you play and then you can hang out afterwards and have a drink

with the audience, as opposed to being some guy who sits up

on stage and doesn’t communicate at all other than playing the

piano.” I like the sentiment — and Rhodes is just the right

man to carry it out. Just don’t make the mistake of underestimating

his artistry, because he communicates with the piano, too.

Brian Reinhart

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews