|

|

|

Availability

Download: AmazonUS

|

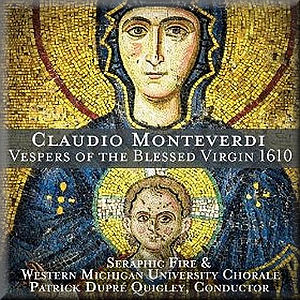

Claudio MONTEVERDI

(1567-1643)

Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610) [60:53]

Magnificat a 6 [17:01]

Joel Spears (lute, theorbo), Philip Spray (violone), Scott Allen

Jarrett, Karl Schrock (chamber organ)

Joel Spears (lute, theorbo), Philip Spray (violone), Scott Allen

Jarrett, Karl Schrock (chamber organ)

Seraphic Fire and Western Michigan University Chorale/Patrich Dupré

Quigley

rec. 11-15 March 2009, Nazareth College Chapel, Kalamazoo, Michigan

SERAPHIC FIRE MEDIA SFM107 [77:55]

SERAPHIC FIRE MEDIA SFM107 [77:55]

|

|

|

This is a fascinating and very well produced performance and

recording. It has generated a good deal of critical acclaim

and general interest. In August 2010 the news went out that

this self-released recording had “soared to #1 on the

iTunes classical chart over the weekend, and briefly rose above

pop diva Lady Gaga’s The Fame Monster (Deluxe Edition)

on the iTunes all-genre chart”, which is quite an achievement

in anyone’s book (see story on NPR).

The review here is of the CD version, though this does seem

to be easier to acquire as a download.

Since reviewing the recording of this work with the King’s

Consort on Hyperion I’ve yet to find a recording to

challenge it as pre-eminent in the sheer ‘wow factor’

stakes. Seraphic Fire’s performance doesn’t change

my view, but neither does it challenge on an equal basis. Conductor

Patrick Dupré Quigley has made this recording with the

intention of bringing Claudio Monteverdi’s Vespro della

Beata Vergine to the composer’s own age, that of the

late Renaissance rather than the high Baroque of Bach or Handel.

In his booklet notes, Quigley writes: “When one thinks

of Monteverdi’s Vespers, inevitably our mind’s

ear recalls the large-scale performances that have characterized

the many historically informed recordings of this work by Baroque

ensembles... To the 21st-century mind, the Vespers is

synonymous with grandeur, a monolith of early Baroque musical

form. But is this Vespers that we know, with its large

choir and massive instrumental forces, the same one that Monteverdi

himself heard while first composing it? Almost certainly

not. When we think of Monteverdi, we now know him to be

the torchbearer of a new age, a musical predecessor of Bach

and Vivaldi. Monteverdi himself, however, had no concept of

the music that was to come after him - he was a contemporary

of Victoria, a young man during the age of Lassus. In his own

time, Monteverdi’s sacred music was not the beginning

of the Baroque; it was, rather, the pinnacle of the Renaissance.…

One might even assume that the gigantic, set-in-the-grand-cathedral-of-San

Marco performances were the exception rather than the norm.”

This I agree with in general, but there are one or two contradictions

and points to be made on this topic. Quigley’s aim to

work in “smaller forces and [an] intimate atmosphere [to]

yield a version of Monteverdi’s magnum opus that is finally

in tune with the inscription on the score’s title plate:

“’suited for the chapels and chambers of princes’”

falls a little when you see the size of the choir: 12 for Seraphic

Fire and 41 for the Western Michigan University Chorale, which

is a pretty Mahlerian sea of faces. You might fit 53 singers

into the chamber of a prince, but the result would be more Marx

Brothers than Monteverdi. These massed voices are not at work

all of the time, but it does mean that the balance against the

genuinely minimal accompanying instrumental forces is heavily

stacked. With the staggeringly wonderful opening Domine ad

adjuventum you not only miss the extra winds, but can’t

really hear the remaining instruments either, so it sounds like

a perfectly tuned choir singing a capella. The argument for

leaving out the flutes, cornets and sackbuts is marked in the

score, their role being given as ‘optional’. Monteverdi

also indicates that the instrumental ritornelli ‘may be

played or omitted as desired.’ This is all correct, and

I am delighted to have this option of a ‘chamber’

version of the Vespers, but basing instrumentation on

availability and budget would have been as much a feature of

musical life in Monteverdi’s time as it is now in the

world of jazz. The fully orchestrated version is the ideal,

the optional smaller forces a compromise to allow performances

to go ahead even when sponsorship has been withdrawn or all

the brass players have gone off to do a royal wedding in the

next town - if indeed the work was performed at all in the composer’s

lifetime, something for which there is little evidence. I’m

not arguing against a production of this nature, and indeed,

it is enlightening to hear the piece as it will often have been

heard in the past, although if one could afford 53 singers then

the chances are they’d be more likely to have taken the

option of dropping few vocalists and having a decent band in.

Seeing music of this or any period as the result of what was

going on at the time or earlier, rather than as a part of later

periods the composer could never have known is not a new performance

philosophy, and any authentic ensemble presenting Monteverdi

in the mid 20th century style of massed pre-Rifkin

Bach or Handel would have been run out of town long ago. Indeed,

this applies to the inner politics of the work itself, and the

very idea that the Vespers was primarily written for

performance in St Marks in Venice is something of a myth. Monteverdi

may have been writing to impress and with the aim of achieving

the post of maestro di capello there, which did happen

in 1613, but the forces available to the pragmatic composer

in 1610 were those around him in Mantua. The alternative version

of the Magnificat is a different story, with some recordings

such as The King’s Consort offering both the 6 and the

separately composed 7 voice with orchestra versions.

All of this said, this is a very fine performance and recording.

The Seraphic Fire ensemble advertises itself as an ‘all

star’ group, and the standard of the singing here is especially

fine, both in the choral performance and solos. This is essential

in what is indeed a ‘vocal led’ performance, and

I am in awe of the quality of every aspect of the recording

in this regard. The recording is made in an acoustic which,

appropriately, is not as vast as some cathedral spaces used

elsewhere. The general sonic picture is warm and deep, sympathetic

to the lower notes of the chamber organ, though the upper embellishments

in full-on movements such as the aforementioned Domine ad

adjuventum do become rather lost. The tempi are all nicely

in proportion, with no sense of extreme urgency or over sibilance

in the swifter numbers, and a nice sense of space in the movements

where there is a good deal of liturgical text to get through.

The Magnificat is another highly impressive and effective

performance, though there are a worrisome few flat soprano 1

notes in the solo 30 seconds into the opening - the only minor

blemish on an otherwise stunning technical achievement. The

start of the Quia respexit has a real swing, and the

atmosphere in beautiful choral sections such as the following

Quia fecit and the final Sicut erat in principio

is very moving. The King’s Consort version with is the

closest to a like-with-like comparison I have to hand, and the

difference in vocal approach is quite apparent. Robert King

goes for a more active, animated feel in the vocal lines, the

embellishments more energetically projected. The accompanying

instruments are also more present in the recorded balance, though

the general acoustic picture is larger scale, the soloists standing

more apart from the choir. King is not anti-vibrato, but compare

a duet like Esurientes and you do have a different feel

of the phrasing, the Seraphic Fire singers kicking in with vibrato

from the start. The Quigley then does the following Suscepit

without vibrato. This doesn’t bother me particularly,

but some commentators may pick up the decision making here,

perhaps as having a lack of consistency.

This Vespers is less an either-or choice, more a fine

supplement to the more opulently accompanied versions to be

found in the catalogue. The general impression is rounder and

more gentle than usual - appropriate for a ‘chamber’

version of this music, though not without plenty of contrast

and rhythmic energy where required. I would recommend this version

on the strength of its singing, and as a different perspective

on a ‘must have’ masterpiece. Seraphic Fire doesn’t

knock my favourite version with Robert King from its place of

honour, but will take a permanent place at its side.

Dominy Clements

|

|