|

|

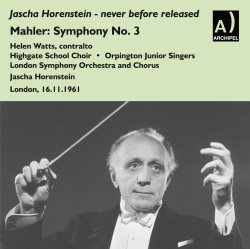

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 3 in D minor [89.37]

Helen Watts (contralto)

Highgate School Choir, Orpington Junior Singers, London Symphony Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

rec. London, 16 November 1961

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op.15 [51.16]

Claudio Arrau (piano)

French Radio and Television Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

rec. Montreux, 17 September 1962

ARCHIPEL ARPCD 0557 [64.20 + 76.23]

This CD preserves a “never before released” live recording

of the first professional British performance of Mahler’s Third

Symphony in 1961. It was given under the baton of Jascha Horenstein,

who did much to spearhead the revival of the composer’s music

during the 1960s. In 1970, three years before his death, Horenstein

returned to the score for a famous studio recording of the same work

with the same orchestra as here. That version on Unicorn remained

as one of the principal recommendations both on LP and CD for many

years.

This live performance does not get off to a very promising start,

with a fluffed note from one of the horns on the very opening beat,

and it cannot be pretended that the sound is anything like as good

as on Horenstein’s studio recording, with the low brass at 1.02

growling rather indistinctly. That said, the internal balance of the

orchestra is good, and they deliver the music with the real joy of

players discovering a new and unfamiliar score. The CD insert —

it would be unduly charitable to call it a booklet — gives no

information at all regarding either the music or its performance,

but the acoustics are rather dry and leads one to deduce that the

venue was the Royal Festival Hall; the 1970 recording was made in

Fairfield Halls. The solo violin at 4.45 is placed very forward in

the mono sound, which leads me to suspect close microphone placement

presumably originating from a broadcast source. Dennis — spelt

Denis on the CD cover credit — Wick’s trombone solo at

5.55 is very stentorian; the same player was more nuanced in 1970.

Later on the internal balance of the orchestra becomes less than ideal,

with the chirruping and squawking woodwind at 20.00 badly masked by

the brass and what sounds suspiciously like panic-stricken recording

engineers reducing recording levels. Unexpectedly the audience bursts

in with applause at the end of the movement; maybe at the original

concert the interval was taken at this point.

The second movement, with its much lighter scoring, produces fewer

problems for the engineers. In the third movement Mahler wrote an

extensive solo for an offstage brass instrument which he originally

designated for the flugelhorn. In later revisions he changed the description

of the instrument to “posthorn”, but this seems to have

been a purely poetic change of title and the part is invariably played

on the flugelhorn – as in Horenstein’s 1970 recording

– although on the CD cover it is stated that Dennis Egan plays

a posthorn. The balance between the offstage instrument and the onstage

players is not ideal, but it does not appear that Egan manages all

the notes with total accuracy, and there is a horrible trumpet error

at 15.43 which sticks out like a sore thumb. Horenstein makes no pause

before the fourth movement — the audience coughing between the

second and third movements is given full measure — but the entry

of Helen Watts is sheer balm. She recorded the part again in the studio

for Solti some years later, in what is otherwise an unpleasantly blatant

reading; Solti re-made the work for his complete Chicago cycle. Here

in the very earliest days of her notable career she is firm as a rock

and as implacable as granite in her declamation of Nietzsche’s

Midnight Song from Zarathustra. And thankfully Horenstein

has no truck with the exaggerated portamento in the woodwind

phrases which Mahler may possibly have intended to imitate the wood

birds of the night but which sound horribly and inauthentically modern

in other performances. The orchestral deep brass sound murkier than

might be ideal, and there are a couple of horn notes that are not

perfectly steady; but this are minor blemishes in an enchanting performance.

Unfortunately there is a CD break between the fourth and fifth movements

— Mahler asks that they should be played continuously —

but this does avoid the sudden interruption in mood which would otherwise

have been perpetrated by the very loud and forwardly-placed bells

at the beginning of the Knaben Wunderhorn song. The choirs

on the other hand are rather backward and far from distinct –

although noticeably below pitch at 1.49 – but Watts is once

again a tower of strength. This is a difficult movement to bring off

in performance, and it is at this point in the recording that one

is aware of a lack of familiarity with the score. The solemn entry

of the strings at the beginning of the last movement brings a real

sense of engagement even though the violin tone could be warmer. It

is nice to hear the period style in the use of string portamento

as specified by Mahler, an effect which became unfashionable for a

time but is an essential part of the composer’s sense of line.

Horenstein sometimes presses forward in a manner which he avoided

in his later recording, but not beyond the bounds of acceptability;

and although another trumpet glitch in the chorale theme at 16.09

is most unfortunate, Horenstein generates a real sense of white heat

in the closing pages. The audience cheers at the end are well deserved.

Horenstein does not appear to have changed his view of the score much

over the years; comparisons of timings in the movements show the first

three rather slower on Unicorn nine years later, while the last three

are slightly quicker. Overall he took some seven minutes longer over

the score in 1970, a fairly minimal difference in a work of this length.

Those who want to hear his interpretation of Mahler’s Third

Symphony will gravitate towards the better sound and less accident-prone

playing in 1970. But they will have to sacrifice Watts’s singing

of the alto solos, richer and more nuanced than Norma Procter on Unicorn.

On the other hand the singing in 1970 of the Wandsworth School Boys’

Choir and the Ambrosian Singers in the fifth movement is more assured

and better balanced than the assembled choral forces were in 1961.

The Unicorn issue however comes without any coupling spread over two

CDs, while here we are also given a very substantial bonus in the

shape of Claudio Arrau’s performance of the Brahms First

Piano Concerto again with Horenstein conducting. Although the

reading has plenty of fire from the opening bars, the recorded sound

is much less satisfactory than in the Mahler with the orchestral playing

decidedly thin in places, and the acoustic is unpleasantly boxy in

the tutti passages. Recording engineers in the studio were

getting much better results at this period. Mercifully Arrau is not

placed too forward in the recorded balance, and we get a good impression

of the sound of his piano. At this stage in his career Arrau was a

more volatile and less monumental player than he became in his later

years, and he forms a dramatic partner for Horenstein who –

as in his contemporary recordings with Earl Wild of the Rachmaninov

concertos – is a sympathetic accompanist. But the horn in the

first movement at 9.31 is a particularly bad example of the weak and

watery tone of French instruments at this period, sounding for all

the world like a tremulous saxophone. If you like this sort of ‘national’

style of playing, you’ll love it; although you may be less impressed

with the squeeze-box effect of the woodwind at the beginning of the

slow movement. This was clearly a very great performance indeed, with

which one is delighted to make acquaintance; but the orchestra and

the recorded sound do rather let the side down.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Masterwork Index: Brahms

piano concerto 1 ~~ Mahler

symphony 3

|

|

|