The reputation of Jascha

Horenstein has never been higher. In

fact I believe his reputation has never

been so high since his death in 1973.

Why else would there be so many reissues

of past commercial recordings and first

time issues of radio archive recordings

as there have been these past few years?

Recording companies do not have money

to burn so they would hardly issue so

much material if they did not know there

was a substantial number of collectors

prepared to buy it.

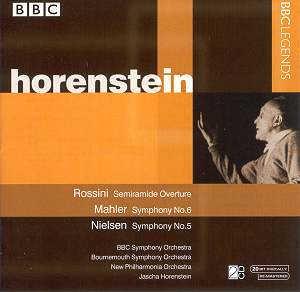

Though by no means

the only label reissuing Horenstein

recordings, BBC Legends was always going

to lead the way with his work since

he was so highly regarded in Britain

for so many years and was broadcast

so often by the BBC. Interesting when

you remember that Horenstein was not

British, so giving the lie yet again

to the oft-repeated urban myth that

the British only like to back their

own artists.

Horenstein was born

in the Ukraine and grew up in Vienna

and Germany and post-war he held American

citizenship. Neither was he ever resident

in Britain, as was wrongly alleged in

a recent review. He was, for most of

the last years of his life, actually

resident in Switzerland. So why did

the British like him so much? Obviously

there was a simple and straightforward

appreciation of a superb musician, but

I have always suspected there was also

an innate sympathy for a character who

clearly didn’t seem to fit anywhere.

Horenstein wore his peripatetic artistic

existence with some unease. To quote

what is an Irish expression, said of

Horenstein by the former leader of the

London Symphony Orchestra Hugh Maguire,

you always had the feeling that Horenstein

"had his feet in the wrong wellies".

Well we British like people like that

and are prepared to give them a chance

when others might not. Not, of course,

that this aspect would ever have saved

Horenstein for longer than a couple

of concerts had he been a second-rater.

There is no more critical and discerning

an audience in the world for classical

music than the British and they would

have sussed out a "wrong-’un"

had Jascha Horenstein been one very

quickly indeed. Horenstein was no second-rater.

He was straight out of the top drawer,

an inheritor of the great tradition.

That is not to say that he got it right

every time. He didn’t. No great artist

ever does that. Be very suspicious of

the Maestro Perfects of this

world. They are often all style and

no substance. Like all the greats, Horenstein

had to dare to fail to succeed and he

sometimes did simply fail. But the failures

were more than outweighed by the successes

which his growing recorded legacy testifies

to. Not ever easy music-making, mark

you. Horenstein was never an easy conductor

to get to know. His was music making

that was always challenging of the audience

and the reaper of rewards only for those

with more than half an ear to hear

rather than just listen.

His appearances in

Britain date from the mid 1950s and

continued unbroken until the year of

his death in 1973. He appeared all over

the country, not just in London, and

in the end was offered the job of succeeding

Sir John Barbirolli at the Hallé

Orchestra in 1970. A position he turned

down because of failing health. But

he was also highly regarded in France

as the issue recently of recorded material

from concerts in Paris spanning ten

years has shown (Music and Arts CD-1146

covering 9 CDs). He also conducted regularly

in the USA. In an interview in Gramophone

magazine around 1970 Horenstein talked

about his reputation in Britain being

largely built on his conducting of Mahler

and Bruckner. I think he regretted this

as he conducted a very wide repertoire

indeed. His last British engagement

was actually Wagner’s Parsifal at Covent

Garden. But it’s true he was known as

a Mahler and Bruckner man for so many

of my generation, each concert or broadcast

by him in those two composers an event

not to be missed.

When the post-war revival

in the interest in Mahler’s music got

underway only Holland could possibly

claim prominence over Britain in being

a more fertile ground for its appreciation

and even that is proved a close-run

thing by the public record. Conductors

such as Horenstein, Goldschmidt, Barbirolli,

Schwarz, Klemperer, Del Mar, Van Beinum,

Steinberg (these last two fine Mahlerians

followed each other as Principal Conductors

of the London Philharmonic), Süsskind,

Hurst, Boult and Groves (who in Liverpool

in the mid-1960s gave the first complete

one conductor/orchestra Mahler cycle

since the 1920s) had led the way in

laying down the foundations for the

great Mahler renaissance in the 1960s.

Their work and the work of critics such

as Deryck Cooke, Donald Mitchell, Neville

Cardus, William Mann and Michael Kennedy

made Britain, all of Britain, a home

for Mahler before many other countries

could catch up in even their capital

cities. People in Manchester, Liverpool,

Bradford, Birmingham, as well as London,

knew their Mahler and knew him well.

Here’s an example. As early as 1960

the distinguished critic Ernest Bradbury

was able to write: "In recent years,

Leeds audiences have done well in the

cause of Mahler and Bruckner and it

is highly likely that the majority of

listeners tonight are by now well acquainted

with the general structure and particular

Lokalton of a Mahler symphony."

It is worth stressing that this is a

city in the provinces of the north of

England Bradbury was writing about,

not London, and in 1960 at that. The

reason for Bradbury’s confidence in

the Mahlerian appreciation of a Yorkshire

audience as early as 1960 was performances

there by, among others, Jascha Horenstein.

In fact so confident were the concert

planners of Leeds in the Mahlerian senses

of their audience as early as 1959 that

Eduard Van Beinum and the Amsterdam

Concertgebouw had been scheduled to

give Mahler’s Seventh in the Town Hall

that year, though Van Beinum’s death

intervened three weeks before the concert

took place. (They got Bruckner‘s Eighth

under Jochum instead and finally heard

the Mahler Seventh under Barbirolli

in 1960. [the first

live concert I attended - LM])

And there in the middle of the great

Mahler movement in Britain from the

late 1950s was Jascha Horenstein. He

had helped Leeds people’s appreciation

of Mahler with the London Symphony Orchestra

in the Fifth Symphony there as early

as 1958. (He recorded it for the BBC

in 1960.) He gave the Eighth in London

in 1959 in a landmark performance also

available on BBC Legends (BBCL 4001-7).

The Fifth again at the Edinburgh Festival

in 1960 with the Berlin Philharmonic.

The First, Fourth and the Fifth were

given in London in 1960 for the centenary

series of every work except the Eighth

which had been played the previous year

under Horenstein. The Third came in

London in 1961 and he would later conduct

the Ninth twice in the capital in 1966

(Music and Arts CD 235 and BBC Legends

BBCL 4075-2). The Sixth would be heard

under him in Bournemouth in 1969 (the

subject of the present review) and back

in London the Seventh later that year

(BBC Legends BBCL4051-2 and Descant

02). There were other Mahler performances

in Britain by Horenstein, of course,

but it is the case that in just over

a decade he had conducted every Mahler

symphony in Britain except the Second.

(He had already given that with the

LSO in South Africa back in 1956.) Finally

"Das Lied Von Der Erde" would

be heard in Manchester in 1972 (BBC

Legends BBCL 4042-2) so completing the

Horenstein British Mahlerfest which

we can now enjoy on CD largely thanks

to BBC Legends. As a matter of interest,

in that same period Horenstein also

conducted all the Bruckner symphonies

in Britain except for the Seventh. So

you can see why his Mahler and Bruckner

reputation was so high in Britain.

Horenstein also recorded

the First and Third Symphonies of Mahler

in the studio for Unicorn in 1969 and

1970 (UKCD2012 and UKCD2006/7). After

his death the company also found a stereo

recording of the Sixth Symphony at Swedish

Radio with the Stockholm Philharmonic

from 1966 (UKCD 2024/5, a concert on

the same night that Bernstein conducted

the Eighth in London with the Horenstein-trained

LSO) and it later appeared on the Music

and Arts label too (CDC 785). This Stockholm

performance had much to recommend it

but there was always, for me, the feeling

of "stopgap" about it. It

revealed enough to show that Horenstein

saw the work as a strictly organized,

classically rigorous drama that stressed

its twentieth century foundations with

a bleak, dogged, unforgiving outlook.

The problem was the orchestra‘s playing.

Whilst I think it is the case that the

Stockholm Philharmonic gave their best

for Horenstein, their best was just

not good enough for his interpretation’s

particular tenor. There is a corporate

lack of concentration over the whole

performance that renders Horenstein’s

uncompromising vision of the work into

mild anaemia and so causes what is a

noble failure. To give what Horenstein

clearly demands, as is borne out by

the Bournemouth performance under review

now, an unbending concentration across

the whole immense work is needed and

the Swedish orchestra is just not quite

up to that. There were later plans for

Horenstein to record the work in the

studio in London with the LSO in 1973

but his death put paid to that. There

it might have ended were it not for

the fact that the BBC possessed this

tape of him conducting the Bournemouth

Symphony Orchestra in the work from

1969. When they re-broadcast it in the

late 1980s in Radio 3’s "Mining

The Archives" series Mahlerites

who admired Horenstein knew that here

was the real deal at last. The fact

that it has taken some years between

that broadcast and this release brings

a case of "better late than never"

and a feeling of gratitude that BBC

Legends has now plugged the penultimate

gap in the Horenstein Mahler discography

at last. There is one final piece in

the Horenstein British Mahler story

to go and that is the Fifth, a work

he conducted at least three times in

Britain in concert. In the archive at

the Barbican Centre in London there

is an "off-air" copy of that

studio recording that he made with the

LSO at BBC Maida Vale Studios in 1960

(Shelfmark A00337, MP Ref: BCT 0344).

Those who have heard it testify to its

musical quality and the acceptability

of the sound so can we hope that BBC

Legends will look into the possibility

of obtaining this for release next?

Horenstein gave a great interpretation

of the Fifth and it deserves to be heard.

The Bournemouth Symphony

Orchestra of 1969 was a fine and versatile

band, well-trained by their Principal

Conductor Constantin Silvestri. So when

Horenstein stepped on to the podium

of the, now demolished, Winter Gardens

in Bournemouth (an indoor concert hall

in case anyone not familiar with British

musical life is wondering) he had before

him an ensemble who were more than capable

of delivering exactly what he meant

in this work and the difference over

the Stockholm version is stunning. This

now supersedes that earlier recording

in every respect but one. You need to

know that this new release is a mono

recording where the Stockholm was in

stereo. The BBC had not stretched to

stereo recording in the English regions

by early 1969 but this is excellent,

well-balanced, firm and undistorted

mono sound that will only displease

the seriously audiophile listener and

bothers me not one jot. What you will

hear is all the details of this score

in excellent, conductor’s balance perspective,

the screaming upper line thrillingly

revealed, the depths of low brass sound

malevolently present and every point

in between in sharp relief.

Horenstein was the

ultimate nihilist conductor. No one

could project bleak despair across the

drama of a work like he could, as can

be judged by his recorded performances

of Mahler’s Ninth. So it is with the

Sixth. What is so remarkable about this

performance is Horenstein’s absolute

determination to allow nothing in that

detracts from the unswerving belief

that this is a work about hope snuffed

out. When you get to the very end, where

the final statement of the cruel march

rhythm first heard near the beginning

and repeated throughout the work sends

the hero to oblivion, you are aware

this is what Horenstein was aiming at

from the start, because he believes

this is what Mahler was aiming for at

the start too. In this way this is the

most focused and distilled performances

of this work I have ever heard and I

doubt many conductors have the intellectual

rigour matching great musicianship to

both take this on board and deliver

it so convincingly. Horenstein always

had the ability to take in a work in

its entirety and this is no better evinced

as here. A brave thing to do, of course.

Remember what I said about daring to

fail to succeed. Take those passages

where the mood seems to lift and there

is light, lyricism and air to contrast

all too briefly with the struggle, tragedy

and mechanistic driving energy of this

Kruppsinfonie. I am thinking

of the "Alma Theme" second

subject of the first movement, the pastoral

cowbells and shimmering strings passages

in the same movement recalled in the

last, the brief celesta-accompanied

tone painting towards the end of the

first movement, the peculiar Trios of

the Scherzo and the whole of the Andante.

The overwhelming impression from the

way he treats these passages is that

Horenstein doesn’t want them to have

too much of an effect on us. He holds

them at arms length by seeming to push

them along at all costs. It isn’t a

case of his rushing these passages.

There is a pressing-on, but not enough

for you to be unaware of them. It is

more that you are not going to be allowed

to make any kind of emotional attachment

to them. This way Horenstein seems to

dangle them in front of us, to tell

us we will never achieve the repose

or comfort they promise, that our doom

is already decreed by fate and so we

may as well submit to it. It’s a remarkable

aspect, moving and unnerving in its

extraordinary honesty, and one he never

forgets to mark when ever the need arises.

This makes this performance so dark

that you may only want to experience

it on a few occasions.

More than any other

Mahler symphony the Sixth is built rigorously

around repeated use of particular rhythmic

figures, thematic groups and chord clusters

held together in a tight four movement

symphonic form. The first movement is

a strict sonata form but the last movement

also has the most careful and easily

discernable structural pillars. This

is all gift to Horenstein’s familiar

ability to forward-plan with modular

tempo that make sure the architectonic

plates that are the structure of the

work never seem to shift. If ever his

gift for picking a more or less single

tempo for a whole movement was going

to work it would be in this symphony.

So it is that the first movement manages

a thunderous, heavy and dogged march

that still keeps grinding away in our

mind as Alma’s second subject group

sweeps in and out at around the same

basic tempo, keeping that sense of creative

detachment already mentioned. Likewise

the coda to the first movement. There

can be performances where the end of

the movement seems to yell out a sense

of triumph, albeit premature. Indeed

this is often an aspect that is used

to justify the placing of the Andante

after the first movement rather than,

as here, the Scherzo. Horenstein, by

not playing for any triumph at all at

this point, justifies triumphantly the

edition of the work he is using: the

1963 Critical Edition by Erwin Ratz

that bravely restored the inner movement

order to Mahler’s original conception

- Scherzo followed by Andante. After

the kind of desperation coda Horenstein

delivers, the assault of the Scherzo

after the first movement sounds dramatically

effective. The Scherzo itself is remarkable

for some whip crack string playing that

slices and slashes across the texture

adding to a poisonous brew that not

even the balm of the Andante will get

rid of. The Andante itself is, as I

suggested earlier, cool and clinical.

It is also all of one minute faster

than the Stockholm performance so Horenstein‘s

aim seemed to be towards ever more classical

framing. Rest for us the music certainly

is, but it is an uneasy rest which is

absolutely appropriate with what is

to come. That is not to say that the

simple presentation of the climax does

not have the power to move. It moves

because somehow Horenstein invests it

again with the feeling that it is a

transitory vision.

Earlier in this review

I mentioned Horenstein daring to fail

to succeed and the last movement illustrates

this well. At over 33 minutes this is

one of the longest versions you will

hear. Horenstein and his players pull

it off, but only just. The upside is

that you can hear instrumental details

and textures as though the score were

laid out before you like a musical equivalent

of a blueprint. The downside is that

there are some passages where I would

forgive anyone for thinking that the

tension drops. The long passage between

the two hammer blows, for example, could

do with a bit more kick. But, as I also

said before, Horenstein never made it

easy for himself, or us, so a bit of

perseverance is called for. The reward

is a truly cathartic experience which

is what this symphony should be in the

end. The hammer blows are superbly placed,

the chase to hoped-for triumph truly

desperate, the crush of fate that much

more terrible for being so grandly and

spaciously stated, the great coda a

fearsome dead zone all masked faces

at a funeral as the mourners gaze into

the grave.

The generous coupling

in this set is Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony,

a work Horenstein had the highest regard

for, as can be heard in his short but

revealing interview with Deryck Cooke

included in this set. It comes from

a BBC studio recording in 1971 and is

in stereo. It has been released before

on the short-lived BBC Radio Classics

label but, for this new release, Tony

Faulkner has performed a new remastering

and comparison shows this to be a marked

improvement. The sound is closer and

much more immediate. Horenstein recorded

the symphony for Unicorn in 1969 and

that version was remarkable for the

astounding side drum cadenza of Alfred

Dukes in the first movement - a berserk

assault with rim-shots cracking off

the sticks like bullets. Mr. Dukes was

not on duty for this BBC recording and

David Johnson, though a fine player,

doesn’t have the manic energy of his

colleague and delivers a more conventional

account of the great drum solo. Under

Horenstein the first movement moves

in two great arcs from the pregnant

opening, through a dogged military march

with side drum in perfect step, a life

affirming lyrical middle section that

scales to a wonderful horn-led climax

and then across the battle between side

drum and orchestra leaving a genuine

desolation at the close where John McCaw’s

eloquent clarinet solo stays in the

memory for a long time. The second movement

has all the energy you could want when

needed, but Horenstein’s acute sense

of the movement’s geography and his

tempo choice allow him to take care

to stress the reflective passages that

are sometimes short-changed by others.

The end brings real release and optimism

and a shout of joy.

The coupling of these

two symphonies is fascinating. They

are separated by just 16 years but also

by the Great War. Both have a first

movement dominated by a militaristic

march rhythm with side drum that both

marches and growls. Both use the march

as a weapon against us. But in the Mahler

the conflict is won by the march and

its allies who destroy the symphony‘s

soul, whereas in the Nielsen the march

and what it represent is finally beaten

down by the forces of light. Nielsen

ends his symphony with an emphatic yes.

Mahler ends his with an emphatic no.

All that needs to be

said about the final item on this set

is that Horenstein more than has the

measure of the mordant wit in Rossini’s

Semiramide Overture and the 1957 mono

recorded sound is spacious but clear.

This item came from the British Library

Sound Archive. I wonder what else of

Horenstein’s they have.

This is a major release

from BBC Legends containing a Horenstein

Mahler Sixth to grace the discography

of this work at last. You will be involved,

you will be moved, you will be unnerved,

you will not be disappointed.

Tony Duggan

BUY

NOW

AmazonUK

AmazonUS