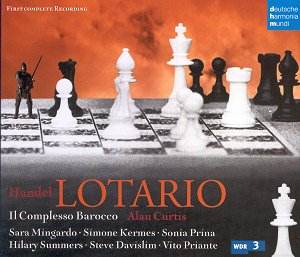

‘Lotario’ was Handel’s

opera designed to show of his new set

of singers with the reformed Royal Academy

(the so-called "Second Academy")

in December 1729. He had spent the summer

on the continent recruiting new singers.

It was not a great success and was not

revived again until the 1950s (when

it was again received without enthusiasm).

So we must welcome this wonderful new

recording from Alan Curtis, which enables

us to appreciate the music - and there

is much good music here - without getting

too hung up on the limitations of the

libretto. On disc, and with a performance

as strong as this, any dramatic problems

matter less.

For a Handel opera,

‘Lotario’ is short; mainly because Handel

set a highly compressed libretto – so

compressed that the action can seem

a little puzzling. And the plot is opera

seria at its most different; the characters

undergo virtually no development. Instead

it is a ‘closed box’ scenario, where

the personalities of a group of people

are gradually revealed through a series

of interactions. The essential nature

of the baroque aria (its presentation

of two contrasting affekts rather than

a linear character development) lent

itself to this form of opera. In ‘Lotario’

the libretto presented Handel with a

series of strong characters in strong

situations.

When recruiting in

Italy, Handel failed to engage the famous

castrato Farinelli, so that his company

consisted of a soprano leading lady

(Anna Strada del Po, who would go on

to create the title role in ‘Alcina’),

an alto castrato (Bernacchi), two contraltos

and a tenor. His second contralto, Antonia

Merighi, generally performed male roles

because of the low tessitura of her

voice, but Handel had already engaged

contralto Francesca Bertolli who specialised

in male roles. So in ‘Lotario’, Merighi

sang the role of the evil Matilde. Merighi

was a fine singing actress, so Handel

created a highly dramatic role which

was equal to her talents.

The plot, such as it

is, is as follows. The King of Italy

has recently died. The evil Berengario,

Duke of Spoleto (Steve Davislim, tenor),

who in fact has murdered the King, and

his equally malevolent wife Matilde

(Sonia Prina, contralto) are attempting

to pressure the late King’s widow Adelaide

(Simone Kermes, soprano) to marry their

son Idelberto (Hilary Summers, contralto).

In fact Idelberto does love Adelaide,

but Adelaide steadfastly refuses to

marry him. Things are complicated by

the arrival of Lotario, King of Germany

(Sara Mingardo, contralto) who loves

Adelaide and wants to save her from

her enemies. By the end of the opera

Matilde and Berengario are defeated,

Idelberto is given their throne and

Adelaide and Lotario declare their love

in a lovely duettino where Kermes and

Mingardo’s voices combine and contrast

beautifully.

As can be seen from

the voice types, Alan Curtis has managed

to cast this opera with a remarkable

trio of fine contralto voices. Each

one, Sonia Prina, Hilary Summers, Sara

Mingardo, has the sort of lovely, dark

chocolate voice which is encountered

all too rare nowadays. The result, with

just a lone soprano, is to give the

opera a remarkable, but not unattractive

dark tint. All three are good Handel

stylists and are a pleasure to listen

to; just occasionally I wished that

there was a little more difference between

their voices, though each one does have

a distinctive timbre. The timbre Sonia

Prina’s voice has echoes of that of

Felicity Palmer. Here Prina has the

gift of a role in Matilde, though I

did wish that she chewed the scenery

more. She rises to the occasion superbly,

though, in Matilde’s final accompagnato,

Furie del crude averno. Sara

Mingardo is wonderfully noble as the

hero, Lotario and Hilary Summers nobly

does her best with Idelberto, a character

who seems rather ill-defined, perhaps

as a result of the cuts in the libretto.

Having seen her as a superb Giulio Cesare,

I wish that the opera gave her rather

more dramatic meat. Steve Davislim gets

to do a lot of huffing and puffing as

the evil Berengario, and he does it

rather well. As the heroine, Simone

Kermes has an affecting, rather fluttery

voice, but she can delivery nobility

and firmness when required.

All the cast are dramatically

credible in their recitatives, making

them involving and shaping them so that

they sound like drama rather than just

preludes to the arias. In the arias

they are very fine stylists, knowing

how to use Handel’s sometimes difficult

vocal lines for dramatic purposes. Not

everything is perfect; Simone Kermes

has a tendency to aspirates in some

of her runs; there are occasions when

Steve Davislim does rather sound like

a car starting, though elsewhere he

turns in some very stylish singing.

But no singer ever loses sight of the

dramatic point; up to a point, I would

far rather a singer err technically

than dramatically in this music. Nowhere

do we get the sort of icy perfection

which can mar this music. Kermes also

indulges in some highly ornate cadenzas

with some stunning high notes, a little

over the top for my taste but not everyone

will agree.

Curtis conducts his

small group (21 musicians in all) in

exemplary style; tempi are just and

the group’s playing is rich and stylish.

The opera is just too long for 2 CDs

so Curtis has trimmed the already compressed

recitative and pruned six da capo arias

down to just their A sections. This

practice does have a precedent in Handel’s

performances of his own operas, but

I could not help wishing that Deutsches

Harmonia Mundi had done what other companies

have done in the past and extended the

opera to three CDs but only charge the

customer for two; then we could have

had the opera properly complete.

The booklet includes

the libretto and translations, but the

English translation used is the one

from the programme for the London premiere

in 1729. This is an affectation that

I wish record companies would get rid

of, I find it rather unsatisfactory

to have to listen to an opera filtered

through the rather arcane language of

the 18th century, something

simpler and more direct would be far

more satisfactory.

Many Handelians will

want this opera to fill in a gap in

their shelves. But for those that are

not completists, buy it anyway for a

fine performance or perhaps buy it as

a present for those friends who think

that Handel’s operas are all too long

and all sound the same.

Robert Hugill