After Giuseppe Verdiís

three great middle period operas, Rigoletto

(1852), Il Trovatore (1853) and

La Traviata (1853), his pre-eminence

as the foremost opera composer of the

day was assured. Now a rich man, his

pace of composition slackened; he was

happy working and expanding his farm

at Santí Agata, or following the unification

of Italy, serving in the first Italian

Parliament to which he was elected in

1861. However, if the price was right,

also the conditions of production and

his required singers were available,

then Verdi answered the call. He went

to St Petersburg where La Forza del

Destino was premiered in November

1862. He later wrote that the subsequent

honours from the state were no compensation

for the cold! His preferred foreign

clime was Paris and 1867 saw his longest

opera, Don Carlos for that city.

In the summer of 1870

Verdi wrote to his publisher Ricordi

ĎTowards the end of last year I was

invited to write an opera for a distant

country. I refusedí. His friend,

Camille Du Locle raised the matter again

and Verdi continued ĎI was offered

a large sum of money. Again I refused.

A month later he sent me a sketch. I

found it first rate and agreed to write

the musicí. The distant country

was Egypt, where the Khedive was anxious

to have an opera on an Egyptian subject

for the new Opera House built in Cairo

to celebrate the opening in the Suez

Canal in November 1869. Aida was ready

for premiere in January 1871, but the

designs and costumes were held up in

Paris by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian

war and it didnít reach the stage until

24 December 1871. A production at La

Scala soon followed on 8 February 1872.

The first UK performance was at Covent

Garden on 22 June 1876.

Aida is one of Verdiís

most popular of operas with its blend

of musical invention and dramatic expression.

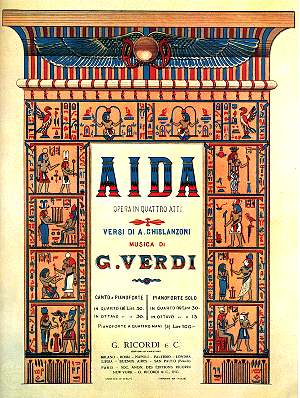

The libretto is by Antonio Ghislanzoni

on a subject by Auguste Mariette developed

by Verdi and Camille Du Locle. This

opera is a work of pageant with its

Grand March (Gloria allíEgitto

Ch. 15) and ballet interludes. It is

also a work involving various personal

relationships. Of these relationships,

the rivalry between Aida, daughter of

the King of Ethiopia working incognito

as a captured slave of Amneris daughter

of the King of Egypt, is intense. Both

love Radames, victorious leader of the

Egyptian army. He loves Aida but is

given the hand of Amneris in reward

for his exploits as commander. Even

more complex is the relationship of

Aida with her father who arrives as

an unrecognised prisoner. The many and

various complex possibilities of the

father-daughter relationship occur throughout

Verdiís operas, but nowhere more starkly

than in this opera where the father

puts tremendous emotional pressure on

his daughter to cajole her lover into

betraying a state secret. This betrayal

will cost the lives of the two lovers.

In some productions

the grandeur of the setting and pageantry

overwhelms the dramatic interactions

and relationships of the individuals.

This minimalist production by cult producer

Robert Wilson would seem to set out

to achieve the contrary effect. There

are no sets and no great pageantry for

the Grand March. At the back of the

stage moving verticals give blank picture

frame spaces that are lit, predominantly

in blue. Across the back silhouetted

figures pass very slowly from time to

time, as does a woman in a scarlet dress

who is clearly visible. The soloists

enter and leave at a snailís pace, sometimes

walking backward, but never, never looking

at each other. All expression is by

slow hand and arm movements. There is

a brief indication on the box that this

manner is influenced by Robert Wilsonís

view of Noh Theatre. I have seen, and

heard, hand-ballet performances where

the movements were clearly aesthetically

and emotionally related. This form has

common usage in Asia. In this performance

there was no relationship that I could

discern between Verdiís melody, the

nature of the dramatic situation and

the speed or nature of the hand, arm

and body movements of the singers. Not

that they are required to move around

the stage very much and certainly never

at speed. Even after a second viewing

I am none the wiser as to why one singer

moves slowly around another from time

to time and on occasions backwards,

slowly moving their arms and hands as

they do so. Regrettably, Wilsonís approach

not only loses the grandeur of the opera

but also fails to illuminate anything

of the relationships of its characters.

This is particularly evident in the

duet when Amneris taunts Aida and tricks

her into confession of love by announcing

Radamesí death (Ch. 14) and the coercion

by Amonasro (Chs. 23-24).

As far as the visual

element of this production, I could

only find two positives. The first is

the evocative backdrop setting and lighting

of the Nile and desert in act 3 (Chs.

20-25). The second is the lighting and

split screen use for the last scene

as the lovers die in the tomb and Amneris

laments above ground (Ch. 30). But even

here there was incongruity. Surely the

music, words and dramaturgy demand the

loversí die in each otherís arms, not

apart. During the Gerard Mortier regime

as Intendant at the Théâtre

Royal de la Monnaie the house audiences

got used to avant-garde productions

and they greet this Aida with polite

rather than enthusiastic applause. When

this production was played at Londonís

Covent Garden, in the November prior

to this filming, it was reported that

the reception in some quarters of the

house bordered on revolution.

Of the singing and

orchestral playing there are more positives.

The conductor plays the music very straight

and does his best to bring out the contrasting

moods of the work. The singers are variable.

Both the Aida of Norma Fantini and Amneris

of Ildiko Komlosiat at least have the

right weight of voice. In Ritorna

vincitor (Ch. 8) and Oh patria

mia (Ch. 21) Norma Fantini phrased

well although she could have used more

sotto voce and her climactic note in

the latter aria was not good. Ildiko

Komlosi sings with full dramatic tone

in the trial scene (Chs. 26-29) although

her voice is not ideally steady under

pressure. As Radames Marco Berti managed

to look even more wooden than the rest;

some achievement. Now a firm favourite

at Verona his voice is best at forte.

He didnít attempt the written diminuendo

art the end of Celeste Aida (Ch.

3) but does manage to soften his tone

and volume for the final scene (Ch.

30) to the benefit of his phrasing and

the pathos of the action. The fact that

the Amonasro of Mark Doss looks Ethiopian

owes more to genetics than make-up and

in contrast with his daughter who is

pure white-skinned to match her dress.

Dossís voice is rather low for a Verdi

baritone, but it is a dramatic instrument.

He does manage to inflect some passion

into his vocal characterisation. His

vocal coercion of Aida by the Nile and

the revelation of himself to Radames

have conviction (Ch. 25). Orlin Anastassov

as the High Priest has the strongest

and steadiest voice on stage. Neither

his costume or make-up reflected his

status in the plot; he looks far too

young.

If the Tate Modern

Gallery in London, where unmade beds

and dissected animals count as art,

are your cup of tea then this Robert

Wilson approach may appeal. To me Verdiís

great masterpiece is much, much more

than this staging portrays. Nor is the

singing of the top rank. More traditional

productions are available on DVD. If

you want Pavarotti as Radames, not his

best role, then there is the choice

of a 1982 La Scala performance with

Maria Chiara as Aida on Arthaus (review)

or with Margaret Price on Warner.(review).

My own favourite, for a grand setting

and magnificent singing, is the 1991

recording from the Metropolitan Opera,

New York, with Domingo and Aprille Millo

in good voice and Dolores Zajick a magnificent

Amneris (DG).

Robert J. Farr

see also review

by Goran Forsling