This is a long file divided into the

following segments:

- Brief description of contents of

each of the eight CDs

- Introduction

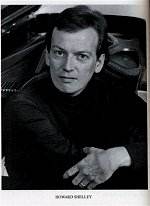

- Howard Shelley

- Review of each CD including full

CD content detail

Brief content

description of each of the eight CDs

CD1:

Morceaux de Fantaisie Op. 3 (1892)

Ten Preludes Op. 23 (1903)

CD2:

Morceaux de Salon op. 10 (1893/4)

Moments Musicaux op. 16 (1896)

CD3:

PiaNo. Sonata No. . 2 in B flat minor

op. 36 (1913) original version

Morceaux de Fantaisie in G minor

(1899)

Three Nocturnes (1887/8)

Four Pieces (?1888)

CD4:

Thirteen Preludes op. 32 (1910)

Prelude in F Major (1891)

Prelude in D minor (1917)

CD5:

Etudes Tableaux Op. 33 (1911)

Etudes Tableaux Op. 39 (1916/17)

CD6:

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor op. 28

(1907)

Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor op.

36 (1931) revised version

CD7:

Variations on a Theme of Chopin Op.

22 (1902/03)

Variations on a Theme of Corelli Op.

42 (1931)

Melodie in E major Op. 3 No.

3 (1940) revised version

CD8:

TRANSCRIPTIONS:

Rimsky-Korsakov – The Flight of the

Bumblebee

Kreisler – Liebeslied

Bizet – Minuet from L’Arlésienne

Suite No. 1

Schubert – Wohin?, from Die

schöne Müllerin

Mussorgsky – Hopak from Sorotchinsky

Fair

Bach – Prelude, from Violin Partita

in E Major

Bach – Gavotte from Violin Partita

in E Major

Bach – Gigue from Violin Partita

in E Major

Rachmaninov – Daisies Op. 38

No. 3

Mendelssohn – Scherzo from ‘A Midsunmmer

Night’s Dream’

Rachmaninov – Lilacs, Op. 21 No. 5

Behr – Polka de V R

Tchaikovsky – Lullaby Op. 16

No. 1

Kreisler - Liebesfreud

Introduction

These recordings were

issued in an 8-CD box set in 1993 bringing

together recordings made between 1978

and 1991 which are still available separately.

I had heard one or two of them over

the years and had been impressed but

it has only been over the last few weeks

that I have realised an ambition and

had the opportunity of listening to

the full set.

I was greatly impressed.

I had known that, over

the years, many of my fellow reviewers

had been equally won over by Shelley’s

poetic, refined readings that consistently

demonstrate his complete empathy with

Rachmaninov’s idiomatic style. Nicholas

Rast, for instance, singled out this

set for inclusion in the ‘Instrumental’

section of BBC Music Magazine’s

Top 1000 CDs Guide (BBC Worldwide

Publications, 1998). Shelley’s recordings

also had excellent reviews in the Penguin

Guide to Compact Discs and Gramophone’s

Classical Good CD Guide.

What

struck me immediately when I began to

assess this 8-CD set was the insightful

notes by Robert Matthew-Walker, especially

his introductory heading: ‘Rachmaninov’s

solo Piano music – the need for reassessment’.

In this introduction, Matthew-Walker

reminds us that Rachmaninov’s reputation

rests mostly on the four Piano concertos

and the Paganini Rhapsody. Little else

was known, virtually every other work

ignored after his death in 1943 until

the 1973 celebrations of the centenary

of Rachmaninov’s birth, when interest

in his symphonies, operas and chamber

and recital music was rekindled. Of

his solo piano music perhaps, only his

famous Prelude in C sharp minor (one

might say infamous in that he was haunted

by it and expected to play it as an

encore at so many of his recitals) remained

well known.

What

struck me immediately when I began to

assess this 8-CD set was the insightful

notes by Robert Matthew-Walker, especially

his introductory heading: ‘Rachmaninov’s

solo Piano music – the need for reassessment’.

In this introduction, Matthew-Walker

reminds us that Rachmaninov’s reputation

rests mostly on the four Piano concertos

and the Paganini Rhapsody. Little else

was known, virtually every other work

ignored after his death in 1943 until

the 1973 celebrations of the centenary

of Rachmaninov’s birth, when interest

in his symphonies, operas and chamber

and recital music was rekindled. Of

his solo piano music perhaps, only his

famous Prelude in C sharp minor (one

might say infamous in that he was haunted

by it and expected to play it as an

encore at so many of his recitals) remained

well known.

It is interesting,

too, to note how the Russian Revolution

marked a watershed in the composer’s

life and how his priorities had to shift

in consequence. In the 26 years from

1891 to 1917 Rachmaninov composed 39

works with opus numbers, but during

the remaining 26 years of his life he

added only six more. In exile, from

1917 to 1943 he had to support his family

and so an exhausting round of recitals

claimed much of his time that might

otherwise have been devoted to composition.

But then, for a good part of this period,

he felt himself out of joint with the

times and intimidated by the new fashions

in musical styles.

Rachmaninov was of

course famed as a virtuoso pianist of

legendary accomplishment. As a pianist

he had no peer. His music written for

solo piano understandably has considerable

technical insight. But Rachmaninov’s

piano writing is certainly not empty

display, it was never written just for

effect. There is great subtlety and

artistry in every piece – music of the

highest calibre.

Comparing these Shelley

recordings with those of Rachmaninov

*, one is impressed with how Shelley

so closely identifies with Rachmaninov’s

idiomatic style. Here, consistently,

is virtuosity of a very high order together

with refinement and elegance, wit, expressive

power, beauty and poetry. There is subtlety

of light and shade, dynamics and expression.

There is considerable thought and eloquence

given throughout even extending to the

pauses. Take just one example. Listen

to the amazing sensitivity and technical

skill in Shelley’s playing of the Prelude

No. 5 in G major from the Op. 32 Thirteen

Preludes - the conjoining of multiple

ripple patterns so lucidly and so lovingly

portrayed.

[* RCA’s 10-CD set

(RCA Victor Gold Seal 09026 61265 2)

‘Sergei Rachmaninov - The Complete Recordings’

published in 1992 comprised recordings

of Rachmaninov, himself, as soloist

in his Four Piano Concertos and Paganini

Rhapsody, and, as conductor, of his

Third Symphony and the Isle of the

Dead; plus solo Piano recordings

of music by many composers – as well

as some of his own compositions including

three of his Etudes Tableaux

(in C and E flat from Op. 33 and in

A minor from Op. 39) and eight Preludes

including three recordings of that famous

one in C-sharp Minor that haunted so

many of his recitals.]

Howard Shelley

For complete biographical

details of Howard Shelley I would refer

readers to his agent’s web site – www.carolinebairdartists.co.uk/html/cbartists.htm

Howard

Shelley is not just renowned as a concert

pianist (especially celebrated as an

interpreter of Rachmaninov par excellence)

but also as a conductor with the London

Philharmonic, London Symphony and Royal

Philharmonic Orchestras and many other

orchestras throughout the world. He

has held positions of Associate and

Principal Guest Conductor with the London

Mozart Players in a close relationship

of over twenty years and he has toured

with them across the globe. Shelley

has also been Principal Conductor of

Sweden’s Uppsala Chamber Orchestra and

works closely with Camerata Salzburg.

He has worked with many other chamber

orchestras.

Howard

Shelley is not just renowned as a concert

pianist (especially celebrated as an

interpreter of Rachmaninov par excellence)

but also as a conductor with the London

Philharmonic, London Symphony and Royal

Philharmonic Orchestras and many other

orchestras throughout the world. He

has held positions of Associate and

Principal Guest Conductor with the London

Mozart Players in a close relationship

of over twenty years and he has toured

with them across the globe. Shelley

has also been Principal Conductor of

Sweden’s Uppsala Chamber Orchestra and

works closely with Camerata Salzburg.

He has worked with many other chamber

orchestras.

He has made many recordings

for Chandos, Hyperion and EMI including

this award-winning set of Rachmaninov’s

complete solo Piano music, plus Rachmaninov’s

concertos, plus series of Mozart, Hummel,

Mendelssohn, Moscheles and Cramer concertos

as well as all Gershwin’s works for

Piano and orchestra and a series of

British concertos including Alwyn, Bridge,

Howells, Rubbra, Scott, Tippett and

Vaughan Williams.

The Reviews

Howard Shelley plays the complete Piano

Music of

Sergei RACHMANINOV

(1873-1943)

HYPERION CDS44041/8

CD1:

Morceaux de Fantaisie

Op. 3 (1892)

No. 1 Elégie in E minor

No. 2 Prelude in C sharp minor

No. 3 Mélodie in E major

No. 4 Polichinelle

No. 5 Sérénade in B flat

minor

Ten Preludes Op. 23 (1903)

No. 1 in F sharp minor

No. 2 in B flat minor

No. 3 in D minor

No. 4 in D major

No. 5 in G minor (1901)

No. 6 in E flat major

No. 7 in C minor

No. 8 in A flat major

No. 9 in E flat minor

No. 10 in G flat major

recorded on 15, 16 September 1982, 19

April 1983

HYPERION CDS44041 [59:34]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA

66081

Appropriately, one

might think, this first CD kicks off

with Rachmaninov’s five-piece Morceaux

de Fantaisie of 1892. The set includes

that Prelude in C sharp minor a

piece that was to haunt him throughout

his career as a virtuoso pianist. It

was composed, the first of the set,

in 1892 for the 19-year-old composer-pianist’s

professional debut. It was to become

his most internationally famous composition

and travelled the world with him. 1920s

New York even had a jazz version played

by the Paul Whiteman Band, which incidentally

Rachmaninov enjoyed. It certainly spread

the fame of the young composer, so much

so that by the time he reached his late

twenties, he was known to a large international

public. On the other hand, its immense

popularity came to be a curse to him

when he became a touring virtuoso; so

many audiences insisted on hearing it

as an encore. Howard Shelley’s thoughtful

reading plumbs its depths, the opening

section suggesting some dark, mysterious

tragedy before the grand theme defiantly

asserts itself.

The C sharp minor Prelude

is the second of the five Morceaux

de Fantaisie, dedicated to Arensky.

Heard together, they demonstrate an

impressive emotional range. The opening

piece is an eloquent, heart-felt ‘Elégie’,

the ‘Mélodie’ with its plaintive

ostinato is tenderly romantic, the whimsical

‘Polichinelle’ points towards the bombast

and the bravura romanticism of the Piano

concertos, and the Spanish-like ‘Sérénade’

is attractively pensive and slightly

melancholy. Shelley delivers very characterful

readings that delight the ear and stimulate

the imagination.

The Ten Preludes include

two popular favourites: the attractive

proud melody and flowing romanticism

of No. 2 in B flat minor, and the splendour

of the assertive No. 5 in G minor with

its meltingly lovely trio that surely

equals anything in the concertos.

The first of the Preludes

in F sharp minor is beautiful, sylvan,

dreamy; the enigmatic No. 3 in D minor

is slightly assertive and vaguely militaristic;

Nos. 4 in D major and 6 in E flat major

return to tenderness and dreams with

yet more touching melodies enchantingly

and most poetically played. Nos. 7 in

C minor, 8 in A flat major and 9 in

E flat minor have rippling chords in

common; although pleasant enough, they

do not reach the same level of inspiration

as the others in the set. The lovely

final Prelude in G flat major is a deeper

creation, bitter-sweet and nostalgic.

CD2:

Morceaux de Salon op.

10 (1893/4)

Nocturne in A minor

Valse in A major

Barcarolle in G minor

Mélodie in E minor

Humoresque in G minor

Romance in F minor

Mazurka in D flat major

Moments Musicaux op. 16

(1896)

Andantino in B flat minor

Allegretto in E flat minor

Andante cantabile in B minor

Presto in E minor

Adagio sostenuto in D flat major

Maestoso in C major

recorded on 11, 12 April 1985

HYPERION CDS44042 [56:17]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66184

Rachmaninov’s Morceaux

de Salon, composed during

December 1893 and January 1894, were

conceived during a period of depression

and consequently the inspiration tends

to be second-drawer.

The opening ‘Nocturne’

quotes from Tchaikovsky’s ‘memorial’

Trio, written in memory of Nicholas

Rubinstein. It is a curious piece beginning

in melancholy and shifting to a rhythm

that is hardly associated with a Nocturne

or lullaby for it almost canters rather

than gently rocks. The pieces are deemed

‘salon’ and the beginning of the second

‘Valse’ seems to confirm this description

but the piano writing soon becomes so

decoratively complex and so virtuosic

that the music is elevated above the

genre. As Robert Matthew-Walker observes

"… in the relative major, [it]

exhibits a ghostly textural reminiscence

of Chopin’s A flat major trio."

Shelley makes the rippling waters of

the comparatively well-known ‘Barcarolle’

glisten. The Mélodie follows

logically on from the ‘Barcarolle’ the

Piano musing over the ripples before

the melody broadens out to a more overt

statement of its beauty. The playful

‘Humoresque’ is full of joie-de-vivre

with a touch of poignancy. ‘Romance’

is more inhibited and elusive, a poem

of regret. The final item is a ‘Mazurka,

the longest piece of the set at nearly

five minutes, is brash and confident,

majestic and fiery.

The Moments Musicaux

are all related using a theme stated

at the outset of the ‘Andantino’. It

has a haunting, magical quality, and

a sense of remoteness and loss. It seems

almost improvisatory and for much of

its span one might easily visualise

an unrelenting but varying pattern of

pattering rain on the still surface

of a lake. This patterning is discernible

too in the following ‘Allegretto’ but

a definite romantic idea emerges and

there is material and atmosphere reminiscent

of the Piano concertos. The ‘Andante

cantabile’ is a song of Slavonic melancholy,

wholly Russian, a very slow variation,

deliberate and almost funereal. The

‘Presto’ is a deluge of left-hand sextuplets

against a rising quasi-militaristic

idea; while the lovely rocking ‘Adagio’

is a gentle sweet contemplation. The

final ‘Maestoso’ surges majestically

with the theme intricately woven into

florid passage-work.

CD3:

Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor

op. 36 (1913) original version

Morceaux de Fantaisie

in G minor (1899)

Song Without Words

Piece in D minor (1917)

Fughetta in F major (1899)

Fragments (1917)

Oriental sketch (1917)

Three Nocturnes (1887/8)

No. 1 in F sharp minor

No. 2 in F major

No. 3 in C minor

Four Pieces (?1888)

Romance in F sharp minor

Prelude in E flat minor

Mélodie in E major

Gavotte in D major

recorded on 17, 18 July 1985

HYPERION CDS 44043 [59:36]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66198

Rachmaninov’s Second

Sonata in B flat minor was written at

the same time as The Bells,

in Rome where he had taken his family

for a six-month sojourn in 1912/13.

The first movement, at one point, actually

suggests tolling bells. It is a kaleidoscopic

and capricious movement: it glitters,

it dances, it is pensive, it postures,

there is a hint of a cake-walk and syncopation

and it echoes the bravura sections of

the Third Piano Concerto

The sweet reveries

of the second movement enchant. As Robert

Matthew-Walker in an untypical flight

of fancy describes it thus (he does

not mention whether this is his visual

interpretation or that of the composer):

"It is a quiet summer’s day in

Southern Russia, with the butterflies

gently fluttering against the rich colours

of the motionless roses and lilacs in

full bloom, the grass warmed with haze,

the earth full yet No. t damp underfoot."

This is one of Rachmaninov’s loveliest

slow movements. The finale is bursting

in energy and again there are echoes

of the fiery sections of the Third Piano

Concerto. Rachmaninov would revise this

B flat minor Second Sonata in 1931 (see

review of it on CD 6)

The remainder of CD3

comprises shorter pieces. First three

separate miniatures lasting just over

one minute each: the swiftly moving

and rippling Morceau de Fantaisie

in G minor (1899) was the first

work completed by Rachmaninov after

the disastrous premiere of his First

Symphony; Song Without Words

is a much earlier little gem (1887),

sentimentally lyrical; and Piece in

D minor is even earlier (1884) but shows

an impressive early assurance, swift

and romantic. Fughetta in F major

is nicely classical, poised and lucid.

Fragments comes from the period

in the weeks immediately before Rachmaninov

fled Russia and the Bolshevik revolution.

It has all the nostalgia for a way of

life gone for ever. Oriental Sketch

from the same period refers No. t to

the geographical region but to the Orient

Express, Kreisler thought the repeated-note

figure reminded him of that great train.

Rachmaninov’s Three

Nocturnes in F sharp minor, F major

and C minor respectively are from 1887/8

and they are all sweetly melodic although

they are hardly restful through much

of their length, in tempi and dynamics.

The CD closes with Four Pieces

dating from about 1897. These are little

gems too. The opening ‘Romance’ shares

the same key and tender utterances as

the First Piano Concerto; the ‘Prelude’

is a tussle between a repeated melodramatic

figure and a more relaxed gentle melody.

Mélodie has one of those gorgeous

melting Rachmaninov tunes and the final

Gavotte charms.

CD4:

Thirteen Preludes op. 32 (1910)

No. 1 in C major

No. 2 in B flat minor

No. 3 in E major

No. 4 in F minor

No. 5 in G major

No. 6 in F minor

No. 7 in F major

No. 8 in A minor

No. 9 in A major

No. 10 in B minor

No. 11 in B major

No. 12 in G sharp minor

No. 13 in D flat major

Prelude in F Major (1891)

Prelude in D minor (1917)

recorded on September 17 and 18 1982

and 20 April 1983

HYPERION CDS44044 [48:13]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66082

Rachmaninov’s group

of Thirteen Preludes Op. 32 of 1910

followed on from his Third Piano Concerto

premiered in New York the year previously

and the Liturgy of St John of Chrysostom.

The whole set was completed within nine

days in the summer (he wrote three of

them on August 23rd). Hurried

they may have been, but these Preludes

are top-drawer Rachmaninov. As a result

of this concentrated activity, maybe,

the pieces show an organic unity. It

is however interesting to note, as Robert

Matthew-Walker observes in his programme

note, "how the composer recalls

the C sharp minor the begetter of the

entire set of Preludes, in the pervasive

cell, and uses much of the material

from the first to be written (No. 5)

in the remaining twelve."

That haunting, dream-like

Prelude No. 5 in C minor is delectable.

Howard Shelley bestows magic upon its

gently coruscating ripples and

serene lyricism. If I had to pick but

one piece from this entire 8-disc set,

this would have to be my choice. The

other 12 preludes cover a wide variety

of tempi, rhythms and moods: the dainty

ballet-like figures of No. 2 in B flat

minor; No. 3 in E major’s bell-like

figures and the bold material reminiscent

of the Piano Concertos; the tenderly

romantic waltz that is No. 9 in A major;

the swiftly-moving restlessness of No.

8 in A minor; the folk-like quality

of No. 11 in B major and the deeply-felt

sorrow and fervour of No. 13 in D flat

major. Then there is the heart-felt

pathos and passion of the most extended

Prelude (at just over six minutes),

No. 10 in B minor. Another piece that

haunts.

This fourth CD is rounded

off with two more Preludes. The pretty

Prelude in F Major was composed two

weeks after completing his First Piano

Concerto. It muses on material from

the slow movement of that Concerto but,

interestingly, it was first published

not as a piano work but as the first

of Two Pieces for cello and Piano

. Listening to it, I was struck by how

much it reminded me of the piano music

of the English composer, John Ireland.

The Prelude in D minor from 1917 was

written shortly before Rachmaninov had

to flee his homeland and maybe here

we can detect a note of regret for the

passing of the old order?

CD5:

Etudes Tableaux Op. 33

(1911)

No. 1 in F minor

No. 2 in C major

No. 3 in C minor, Op. posth.

No. 4 = Op. 39 No. 6

No. 5 in D minor, Op. posth.

No. 6 in E flat minor

No. 7 in E flat major

No. 8 in G minor

No. 9 in C sharp minor

Etudes-Tableaux Op. 39

(1916/17)

No. 1 in C minor

No. 2 in A minor

No. 3 in F sharp minor

No. 4 in B minor

No. 5 in E flat minor

No. 6 in A minor

No. 7 in C minor

No. 8 in D minor

No. 9 in D major

recorded on 19 and 20 April 1983

HYPERION CDS44045 [58:50]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66091

The very title Etudes-Tableaux

suggests extra-musical subjects but

‘tableaux’ in this context, should be

interpreted as meaning the rather indefinite

‘character’ rather than the definite

‘picture’. Rachmaninov observed: "I

do not believe in the artist disclosing

too much of his images. Let them paint

for themselves what it most suggests."

Nevertheless we know

that, in 1930, Rachmaninov provided

Ottorino Respighi with some sort of

programmatic guide to enable the Italian

composer to orchestrate five of these

Etudes-Tableaux. Some might argue

that Rachmaninov’s visualisations were

somewhat contrived, and visualised after

the pieces were composed. (The first

set of nine Etudes –Tableaux

were composed in 1911 and the second

set 1916/17. Three of the original set

were removed one, No. 4 being revised

in 1916, and incorporated (as No. 6

) into the second set; Nos. 3 and 5

from the first set were found after

the composer’s death and reinstated

into the first set.

The Etudes-Tableaux

contain many typical Rachmaninov fingerprints.

So, rather than tire the reader with

repetitive comments on all 17, I shall

restrict myself to commenting on a representative

selection including the five that Respighi

orchestrated. No. 1 of the Opus 31 set

begins assertively in march rhythm before

a delicate rippling theme of considerable

nostalgic beauty tries to break through

the harshness. In No. 2 that pleading

beauty is caught dancing in lonely remoteness.

No. 3, published posthumously, is much

more solemn, pensive; then a defiance

that is washed away by tender, quiescent

ripples before a heart-on-sleeve melody,

reminiscent of those of the Piano Concertos,

enters to beguile the ear. The next,

No. 4 is one of Rachmaninov’s call-to-arms

but with soothing gentle asides. Pressing

on to No. 7 in the set, and the only

Op. 33 Etude Tableau that Respighi

orchestrated, Rachmaninov suggested

a scene at a fair and there is certainly,

in the piano original, a jolly rowdiness

about. No. 8 is another reflective piece

of sylvan pellucid beauty.

Respighi orchestrated

four of the nine Op. 39 Etudes-Tableaux.

Rachmaninov’s wife suggested pictures

of seagulls and the sea for No. 2. On

hearing it, one is immediately reminded

of Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead

and his idée fixe, the

Dies irae. Both the Rachmaninov

piano original and the Respighi orchestration

are powerful and evocative. The Rachmaninov

visualisation of No. 6 was the fairy

tale of Little Red Riding Hood and the

brusque heavy opening piano chords certainly

suggest the wolf and the contrastingly

plaintive little heroine. No. 7, the

most extended of all the Etudes Tableaux

drew an untypically detailed description

for Respighi from Rachmaninov: "Let

me dwell on this a moment longer. I

am sure you will not mock a composer’s

caprices. The initial theme is a march.

The other theme represents the singing

of a choir. Commencing with the movement

in semiquavers [sixteenth notes] in

C minor and a little further on in E-minor,

a fine rain is suggested, incessant

and hopeless. This movement develops,

culminating in C minor – the chimes

of a church.

The finale returns

to the first theme, a march." The

imagination might suggest the funeral

of a great man, mourners hunched against

the rain. The piano intimates all of

this and Respighi’s imaginative orchestration

seems to substantiate such a picture.

Respighi’s orchestration

of No. 9 was based on Rachmaninov’s

visualisation of his final Etude-Tableau

as something of an oriental march and

perhaps a fairground and again the piano

original is equally evocative of such

a scene.

CD6:

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor op. 28

(1907)

Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor op.

36 (1931) revised version

HYPERION CDS44046 [57:09]

rec. 24 and 25 January 1982

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66047

In November 1906, Rachmaninov

deciding that he needed to have a break

from the tensions of social unrest in

Russia and the responsibilities of conducting

at the Bolshoi, settled with his family

in Dresden. It was here that he worked

simultaneously on three works: his opera

Mona Vanna, the Symphony No.

2 and the First Piano Sonata. With CD6,

of this set, we arrive at this latter

work, the most extensive and most formidable

of his solo Piano works. Howard Shelley

rises magnificently to its considerable

challenges realising its symphonic stature

and bringing poetic sensibility to the

lovely slow middle movement as well

as strength and stamina in the outer

movements of this masterpiece of Piano

writing that spans some 37 minutes.

Rachmaninov said that the Sonata’s three

movements were suggested by Goethe’s

Faust portraying Faust, Gretchen

and Mephistopheles and the flight to

Brocken as in Liszt’s Faust Symphony.

The daintiness and vulnerability

of the central movement clearly suggests

the femininity of Gretchen and there

is wry humour in the early sections

of the fiery and passionate Finale,

so full of Mephistopholean strutting

and mockery. Incidentally the closing

section of this Sonata’s Finale alludes,

somewhat appropriately, to the composer’s

idée fixe, the Dies

irae

Rachmaninov’s revision

of his Second Piano Sonata (originally

written in 1913.) lightens its texture

and tightens its arguments thus:-

1st

Movement 2nd Movement 3rd

Movement.

Original version 11:19

7:36 7:21

Revised version 8:01 5:57

5:41.

[The original version is on CD 3 of

this set and reviewed in the appropriate

section above.]

Opinions vary as to

the effectiveness of the revisions.

Rachmaninov, himself, passing judgement

on the original version said, "So

many voices are moving simultaneously,

and it is too long ..." Rachmaninov’s

close friend Horowitz felt that the

1931 revision was too thorough-going.

Rachmaninov concurred and suggested

that Horowitz might like to produce

a version himself. Robert Matthew-Walker

suggests pianists today are more like

to be drawn to the first version but

both have merits and they should both

be considered. The opening movement

music, in the revised version differs

in character. For instance the bell-like

passages seem to be emphasised more

strongly while the cake-walk-like figures

and syncopations are evened out somewhat.

The essential character of the lovely

central movement is maintained and,

I think, enhanced.

CD7:

Variations on a Theme of Chopin Op.

22 (1902/03)

Variations on a Theme of Corelli Op.

42 (1931)

Melodie in E major Op. 3 No.

3 (1940) revised version

HYPERION CDS44047 [51:42]

rec. November 1978

Available separately on Hyperion CDA66009

These two sets of solo

piano variations are from opposite ends

of the composer’s career. The Chopin

Variations was Rachmaninov’s first

big solo piano work. The theme is one

of Chopin’s Opus 28 Preludes. The Corelli

Variations was his last original work

for solo Piano . In this instance, the

theme, interestingly, is not by Corelli,

but rather an anonymous tune known as

‘La Folia’ used by Corelli in a work

of his own. The Chopin Variations

have echoes of Rachmaninov’s Second

Piano Concerto and the Corelli Variations

are not unlike the variations of the

famous Paganini Rhapsody for

Piano and orchestra composed three years

or so later.

The form of the Chopin

Variations is of interest. The 22

variations are grouped

irregularly, giving

an outline of a four-movement sonata.

(First movement: variations 1 to 10;

second movement: variations 11 to 18;

the ‘scherzo’: variations 19 and 20;

and the ‘Finale’: variations 21 and

22. In most cases, each variation is

longer than its predecessor giving the

impression of a cumulative journey of

wholly organic growth. The final 22nd

variation has a duration, in Shelley’s

recording, of just over 5 minutes.

After the grandiose

statement of the theme, the opening

three variations proceed in Bach-like

classicism; the single-line first variation

becoming the counter-subject for the

second and canonic material for the

third. Classicism melds beautifully

with typical Rachmaninov ‘heart-on-sleeve’

romanticism in these variations. Throughout

these variations Rachmaninov exhibits

an assure mastery of large-scale structure.

The Corelli Variations

is dedicated to Fritz Kreisler, who

introduced the theme (see above) to

Rachmaninov. Rachmaninov had recorded

Sonatas by Beethoven, Grieg and Schubert

with Kreisler. Compared with the Chopin

Variations this work is leaner and

seems to have been conceived in one

sweep. The Corelli Variations

are set in Rachmaninov’s favourite key

of D minor. The first 13 variations

share this key and they culminate in

a cadenza in D flat major. As in the

Paganini Variations, this key

is the emotional heart of the work.

D minor returns, for the four variations

before the coda building up to a fiery

conclusion.

Howard Shelley delivers

bravura performances of both sets of

variations, poignancy and delicacy with

the utmost clarity in the fastest passages

and steeliness in the more bombastic

CD8:

Rimsky-Korsakov – The Flight of the

Bumblebee

Kreisler – Liebeslied

Bizet – Minuet from L’Arlésienne

Suite No. 1

Schubert – Wohin?, from Die

schöne Müllerin

Mussorgsky – Hopak from Sorotchinsky

Fair

Bach – Prelude, from Violin Partita

in E Major

Bach – Gavotte from Violin Partita

in E Major

Bach – Gigue fronm Violin Partita

in E Major

Rachmaninov – Daisies Op. 38

No. 3

Mendelssohn – Scherzo from ‘A Midsummer

Night’s Dream’

Rachmaninov – Lilacs Op. 21 No.

5

Behr – Polka de V R

Tchaikovsky – Lullaby Op. 16

No. 1

Kreisler - Liebesfreud

recorded on 20, 2l and 22 February 1991

HYPERION CDS44048 [45:48]

Available separately on HYPERION CDA66486

In Rachmaninov’s youth

learning the classics via piano transcriptions

was the norm. In those pre-radio, pre-gramophone

days, one learnt largely by playing;

concerts were rare events. Rachmaninov,

therefore, regarded transcriptions as

a normal part of music-making. Some

editions of his own later works, thought

to be transcriptions (e.g. ‘Daises’

and ‘Lilacs’) are in fact the original

versions.

All Rachmaninov’s transcriptions

are of a very high technical and artistic

order.

All are faithful to

the spirit and character of the originals

but with added dimensions of atmosphere

and dramatic evocation. The writing

is often very elaborate, and the chord

clusters dense, challenging all but

the most virtuosic pianists. Howard

Shelley rises to their challenges with

aplomb delivering readings full of dash

and sparkle and sensitivity.

Rachmaninov’s first

transcription for solo piano, written

at the time (September 1900) when he

was undergoing psychotherapy with Dr

Dahl, was the ‘Minuet’ from Bizet’s

L’Arlésienne Suite No.

1. Howard Shelley plays Rachmaninov’s

second transcription of this work made

some twenty years later, published in

1923. He makes the music trip along

lightly and merrily through the staccato

rhythms and eloquently through the pride

and languor of the middle section.

Shelley’s reading of

the Schubert Die schöne Müllerin

makes the mill waters swirl and shine

while suggesting the emotional turmoil

of the lovesick boy; while the transcription

of Mussorgsky’s Hopak is a swift-moving,

bombastic virtuoso showcase..

The Bach transcriptions

are wonderfully lucid, late romanticism

lying compatibly side-by-side with classical

purity. Shelley’s Prelude is a model

of clarity and elegance, and his Gavotte

refined and dainty with a hint of wry

humour.

The Flight of the

Bumblebee is ‘busyness’ personified.

Rachmaninov’s most famous transcription

- of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s

Dream Scherzo - has always been

popular. The two sophisticated Kreisler

transcriptions are delicious, lovely,

lilting and sensual. Howard adds poetry

and charm to the delicate, pellucid

beauty of the Tchaikovsky Lullaby.

The Behr Polka is a charming glittering

salon trifle – something of the world

of operetta.

Lilacs and roses adorned

the gate leading to the front door of

Rachmaninov’s country estate at Ivanovka

. Their image must have meant a great

deal to the composer especially during

his years of exile. The two transcriptions

of Rachmaninov’s own works are delectable.

Both fragrantly evocative: dainty ‘Daisies’;

and the ‘Lilacs’ (originally a song)

arpeggios suggest lines of nodding lilacs

swaying in a breeze. [There was also

a ‘White Lilac Lady’ an admirer who

sent Rachmaninov a bouquet of the flowers;

yet they never met.]

Ian Lace