The prospect of seeing and hearing Cecilia Bartoli as Fiordiligi made an extra few days in Zurich irresistible. Hyped and keenly anticipated, the première of the new production by Jurgen Flimm and Oliver Widmer was predictably packed. The opera house is pleasant, traditional and of moderate size, just right for Mozart. From a press seat over the orchestra, the sound under Nikolaus Harnoncourt was bright and inclined towards fierce. Using normal strings and winds, he went for a clinical clarity, natural horns and valveless trumpets, together with small, hard timpani, giving bite to the martial moments, and avoiding any sentimentality. With minimal gesture Harnoncourt kept a firm grip on singers and orchestra, moulding their phrasing with thrusting, forward-moving energy, which was exhilarating and entirely persuasive and won universal plaudits.

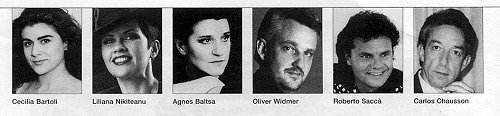

The cast offered integrated, ensemble acting of the high level to which Glyndebourne has accustomed us in UK. Bartoli fitted well into this quite complicated production (see detailed analysis below), acting and duetting well with her sister Liliana Nikiteanu and alternative lovers Roberto Sacca and Oliver Widmer. Carlos Chausson was in control of his students and the hapless women who became his experimental research subjects, and Agnes Baltsa, a very popular member of the Zurich company, stole her scenes as his mercenary assistant, with her bright tone and easy command of the stage.

That far, all was fine, but the cast had to struggle against fussy stage settings which deliberately countered the gradual emotional involvement with Don Alfonso's puppets which usually takes over in the second act under the spell of Mozart's miraculous music. Tiers of seats of the original lecture theatre setting stayed throughout at the sides, coexisting with various locations suggested for the action, and reminding us never to forget that the whole opera is an experiment, a game played upon the hapless young women and their naive admirers. Easy humour was eschewed so as not to gloss over the misogynist flavour of what feels to be an unpleasant fable.

Continuity was visually disturbed by effects, which alienated some parts of the audience and were greeted with healthy boos at the ends of each act. Indoors and out, water and solid earth were blurred at their margins. An ostrich was brought in, presumably to underline the truism that people fail to recognise the obvious and prefer to keep their heads in the sand. A glass cage descended on the uneasily reunited couples at the end, and snow fell to cover the nuptial party, emphasising that this was no simple tale with a happy ending. Despina, having pocketed her earnings without a qualm, was a little discomfited that the joke had turned sour. Don Alfonso returned to his philosophical books, avoiding recognition of the social effects and implications of his heartless manipulations.

Too familiar perhaps with more traditional interpretations, yet having had no problems with David Freeman's poignant and upsetting seaside version for Opera Factory (just as radical as this one and psychologically far more perceptive, I thought) I sided with those who were unpersuaded by the Zurich 2000 version. (A less hostile view of the visual aspects of this production is offered below.)

Equally serious, Cecilia Bartoli disappointed even some of her fans, and the response at her final curtain appearance was short of tumultuous, with even some shouts of 'voce'. Although she had delighted with her commitment and creamy tone in the ensemble scenes, her voice was weak and uneven, with a disturbing husky, toneless breathiness in some registers, which broke up the line in her solo arias. Bartoli's voice was never large and she appears no longer to have the range and necessary power for Fiordiligi's big arias. Some of these limitations were evident recently in her charming if somewhat muted Almirena in Handel's Rinaldo in London. They were even more pronounced faced with Mozart's cruel demands in this Everest of a role, which needs a soprano with an exceptional range to scale its heights and depths. Per pieta was taken excessively slowly, demonstrating the awkward corners of her voice as she carefully negotiated them. A fallible natural horn in the accompaniment only accentuated the impression of fragility and vulnerability, which went beyond dramatic characterisation, and has begun to worry Cecilia Bartoli's admirers, amongst whom I count myself.

Hear her, though, on CD in Mitridate, put through the hoops in the showpieces of the 15 yr. old Mozart's amazingly virtuoso demands on his singers, and fully in command in the 1998 recording [Decca 460 772-2] purchase . Finally, I mention that at least one Swiss critic found her 'sotto voce' inFiordiligi's per pieta completely effective and affecting, so I offer my own response with some caution.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Cosi fan tutte - some thoughts by Alexa Woolf about the Zurich Opera staging and production

Cosi fan tutte deals with the manipulation of human beings and their complex emotions. The human capacity for change and adaptation is proposed as a morally suspect and pejorative attribute of women.

We are confronted by a steeply raked lecture hall, in which propositions and counter propositions about female trustworthiness are put to 'scientific' testing. A large white cube in the middle of the tromp d'oeuil curtain could be seen as containing the unknown, the genies about to be released by the experiment. A vertical slit appears to divide this lecture hall and from this point we no longer are certain what we see and where we are. The stage picture embodies a sense of instability. The unstable elements of water and reflections are incorporated. A bridge across the water leads nowhere. Giant waves on the back drop turn into landscapes. Windows and their reflections appear. Are we looking in or out? Bits of cut out scenery are shifted across the stage and intersect with other elements. A field of candles, like votive offerings, appears and gets obliterated.

The confusion of shapes and intersecting planes mirrors the emotional confusions, which are set in train by the ruthless exploitation of human malleability.

Akin to a post-modern painting, these ambiguous pictorial elements address themselves to a contemporary audience which is becoming familiar (on stage and off) with uncertainty. The stage picture is open to different interpretations and can be seen as taking issue with cigar-smoking Mafioso, Don Alfonso's simplistic equation - Co-si fan tu-tte.

Alexa Woolf

Return to:

Return to: