Virginia Kennerley is my second cousin, daughter of my first cousin, Adrian Kent and my Oxford friend, Kay Facey. She had seen my eleventh opera, A Will of Her Own and thought that she might be able to help get my 12th opera performed by introducing me to the man who controlled the Wexford Festival.

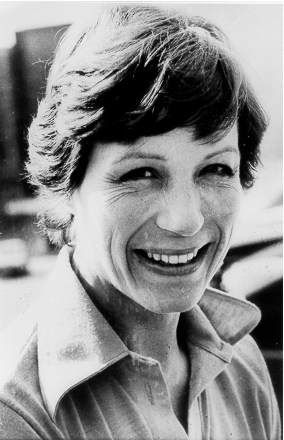

Virginia Kennerley She had come to live in Ireland through marriage with an Irishman and during his lifetime had become an influential journalist. She is now one of the first women priests in the Church of Ireland, Rector of Timolin in County Kildare. She has become the first woman to be made a Canon of the Church of Ireland, at Christ Church Cathedral. When she put me in touch with the controller of the Wexford Festival, I wrote to him explaining the kind of opera I had in mind. It was their usual custom at Wexford to revive some old work that had not taken on in the past but recently they had given a first performance, so that there was every chance that they might do so again and the administrator wrote back quite encouragingly, which gave me the incentive to start on my score. My plan was to write an opera about Caesar and Cicero, the man of action and the man of deliberation who were always being brought together, though they had never been real friends. The opera was to be called The Rubicon, the name of the river in northern Italy which Caesar had been ordered by the Senate not to cross on his way back from Britain and Gaul without disbanding his army for he was suspected of wanting to march on Rome as a Dictator. A feature of this opera is that there are no bowed strings in the orchestra, the sound of the bowed strings being unknown in classical times. There is therefore room in the orchestral pit for the male chorus to be seated there. This enables the Chorus to take part in the description of the Battle of Pharsalus in Act III. In Act I Caesar is seen encouraged by Anthony and others who have been sent to Rome to test the temper of the Senate and the Roman people and cross the Rubicon with his army intact. He is also encouraged to do so by the "Voices behind Scenes", the female Chorus who proclaim themselves as "Fortuna" and promise him a rule of good luck. Confidently he turns to his army (the male chorus in the orchestra) to test their reaction. He alludes to Pompey, who might now be his enemy, but was once his friend, the husband of his only daughter, who sadly had died. So we are prepared for the fact that there may be a powerful enemy awaiting him at home, quite apart from the Senate. But it seems right to go ahead and encouraged by the unanimous good will of his army Caesar brings the curtain down on his confident "Tomorrow at dawn we cross the Rubicon". We see a very different state of affairs as soon as the curtain goes up on the second Act. Already it is being debated whether they should join the forces of Caesar or Pompey. Even the young people are torn between the two camps. Young Marcus (Cicero’s son) is all for Pompey, but young Quintus (Cicero’s nephew) is all for Caesar. Caesar himself calls, to see if he can get the support of Cicero in the Senate, but it is clear that Cicero is not intending to attend. Young Quintus is sternly rebuked by Cicero and his father for having a private word with Caesar as he departed, to the effect that all the young people were on his side. The struggle between Caesar and Pompey comes to a climax in Act III. In the Third Act the struggle between Caesar and Pompey has come to a head. In the first scene we are in Pompey’s camp, where after their recent victory at Dyrachium the Pompeians are already dividing the spoils among themselves, much to the disgust of the Ciceronian party who stand apart, Cicero being ill at the time. Scene 2 brings Caesar’s final victory at Pharsalus with the male chorus joining the orchestra in the description of the battle. In the Third Scene Quintus rates his brother Cicero for backing the wrong horse and squandering all their resources. One of the most effective numbers in the opera is perhaps Cicero’s lament for his daughter whom he loved very dearly, but whom he came back to find dead through childbirth when he returned to Rome after the Civil War.

Caesar comes again to woo Cicero’s support despite the fact that he had joined up with Pompey, but this was for the last time, and perhaps Caesar realised that there was to be no further occasion. In the last scene of Act IV the news comes to Cicero that Caesar has been assassinated. "By whom?" he ask. "By Brutus and Cassius." "Why was I not among them?" He is overjoyed. He has been living in a dream, and now at last he is awake. The Voices behind Scenes encourage him to go forward and cross his Rubicon. He goes forth, destined for a few months to be the Master of the Senate. He supports Octavian, the young man whom Caesar had adopted as his son, without seeming to realise that the main supporter of Octavian, who was later to become the Emperor Augustus, was Antony Cicero suddenly comes to the realisation that by backing Octavian he is also backing the hated Anthony. In the last scene we see Cicero trying to escape but knowing that he is likely to meet with assassins himself. He wonders if there is a life after death. Socrates thought so, the greatest thinker he knew. Perhaps after all death was just crossing the Rubicon. There is the sound of assassins approaching. Cicero has only just time to hurry off. Two men cross the stage with drawn sword.. There is a cry off. The assassins return with Cicero’s head. As soon as I had finished this opera, I sent a copy of the vocal score off to the man whose address I had been given, only to be told by return that he had ceased to be director of the Wexford Festival. I was given the name and address of the lady who had been appointed his successor. She happened to live quite near where I lived in England, so I sent her a copy of my vocal score explaining the situation. I never had reply from this lady. One of the Wexford Festivals was approaching and when I consulted my cousin Virginia as to what I should do she thought it would be best for me to come to Wexford for the forthcoming Festival and meet the new Director on the spot. This I did, only to find that the new Director was a most elusive and aloof person who gave no arrangeable interviews, and generally arrived late at important parties, several of which we attended and then she had her attention fully occupied until the party ended. Virginia and I finally tracked her down on a bare staircase where there was nobody else, but when we broached the subject of my opera, she knit her brow beneath her expensive hair-do. Evidently she had never been told anything about it by her predecessor, or received my letter, or the copy of the score I had sent to her private address, or wanted to know anything about it. Exhausted Virginia and I let her go on her way floating out of our purview. I have never felt so utterly dejected in all my life. I had buoyed myself up with anticipation of a possible performance only to find that as usual my work was completely unwanted. I resolved that in future I would write only to please myself or my loved ones. I could not give up writing operas, for I felt that I had a gift for this occupation, whether rightly or wrongly. So in my last three operas I have written to please myself, or my family. |