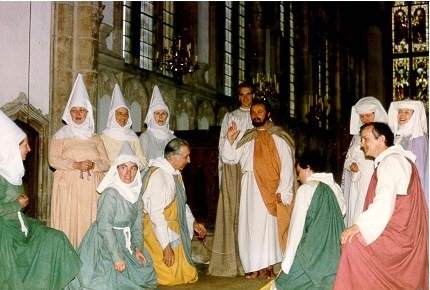

It was a wonderful discovery that long before spoken mystery plays that led to Shakespeare there had been the beautiful sung drama of the Church that led to the Mystery Plays. As Gustav Reese says "The Church was also its principal theatre indeed its opera-house." Starting with the simple question "Quem quaeritis?" (Whom seek ye?) and the answer "Jesum Christum Nazarenum" (Jesus of Nazareth) and the answer to that "Non est hic sed surrexit" (He is not here but risen) this little dialogue was gradually expanded into a whole drama. The drama was naturally sung because priests always do or did, sing, in order that their voices might carry in large buildings. Three priests in their flowing vestment can easily represent the three Maries and it is not long, before each Mary will require a verse, or indeed three verses of her own before they eventually arrive at the steps where the Angel meets them. "Whom seek ye?" Soon the Maries are not satisfied with the little dialogue with which the drama had started. In particular Mary Magdalene will not be satisfied until she sees the Master with her own eyes even if she cannot touch him. Then at last she will be content to turn to the congregation and invite them all to participate. The rest of the drama was celebration. When we performed at Kingston Parish Church one saw how these church dramas could have turned into the mystery plays. The market-place was just outside the church. Perhaps the songs that frequent the Shakespeare plays are a survival from the days when drama was musical. I was fortunate in managing to get from France a copy of the famous Fleury MS which contains one of the best sets of these dramas with music. I was anxious that they should be understood, so I translated the Latin into the beautiful language of the Authorised Version. Fortunately I was able to read the somewhat faded notation and the Latin words on this thirteenth century manuscript. I took a lot of time fitting in the authorised version to the original rhythms in the music. In the MS it was, of course, a single line for the melody with no accompaniment, but I did not think modern singers at any rate could go on perhaps half an hour without any form of accompaniment, so I added a background of sound as tactfully as I could which helped to keep the singer in tune and sometimes used the melody in the accompaniment, especially where it was advisable to remind the singer of his vocal line. What was most interesting was that there were clear indications of recitative followed by arietta so that the later developments of opera were already being indicated. For the first and second acts of our modern performance of these ancient dramas we used The Visit to the Sepulchre and the "Peregrinus" which we called "The Wayfarer". To these we added a drama on the "Ascension" which came from Moosburg. The "Peregrinus" tells the story of the Journey to Emmaus. Cleopas and St. John greet the Stranger who joins them on their walk. He seems to know nothing of recent events in Jerusalem, but discourses on what should be known about historical event. When they draw near to their destination they invite him to join them. "Abide with us, for it is toward evening and the day is far spent." He goes in with them and is recognised in the breaking of bread when He disappears. They rush back to tell the others how they have seen the Lord. The incident of the Doubting Thomas is added to this scene in a very effective way. Thomas declares his doubts then suddenly the risen Christ appears. The whole scene is most moving, especially when acted well, and the work ends very effectively with the whole Chorus singing the passage from the Romans: "Christ being raised from the dead dieth no more." The scholars like to call this the liturgical drama, but there is nothing liturgical about it, except perhaps in its origin. It is plainly an early outflow of opera. The priests were trained singers and they saw that they could give the laity the most vivid idea of these stories by enacting them as sung dramas. They had so inspired the laity that they had encouraged them to make a drama of their own. Unfortunately the priests soon forgot that they had been the original inspiration and gave up the attempt to lead the laity in drama. The spoken play took the place of the sung drama and the subject matter ceased to be sacred. A few centuries later people knew nothing of the sung drama of the Church and thought they had invented opera as a secular form of drama. The practice soon spread to other seasons of the Church year, especially Christmas. The Christmas story was also well suited for treatment in this way. The first play was obviously the Shepherds and their visit to the crib located in the sanctuary where they present their rustic gifts. The Second Play, which is generally called The Star is largely concerned with the Magi who meet, perhaps, at the back of the church and proceed down the aisle led by a boy carrying a long pole with a light at the end of it. They proceed towards Herod’s court, which is located in a side-chapel. A discourse takes place between Herod and the Magi carried by a character called the Knight, who appears to be the general factotum at Herod’s court. Hearing of the Star Herod sets his Wise Men turning up the prophecy of Bethlehem and the Magi are bidden to seek their star in Bethlehem, not forgetting to come back and report to Herod if they find anything. So the Magi proceed on their way to the Crib where they present their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. They are warned by an angel in a dream to go back another way so as to avoid meeting again with Herod. But Archelaus, Herod’s son notices that they have not come and stirs up his father. "You are betrayed, my lord". This is the beginning of the third play, which goes under the name of "Rachel". The opening of this play is marked by the appearance of the Innocents who parade singing their first chorus. They attract the attention of the Knight who seems to think them a suitable victim for the easing of Herod’s anger at being duped by the Magi. "Well counselled, valiant Knight. Let these boys feel the sword thrust and perish." The Knight soon carries out the dastardly project. The Innocents are slaughtered and they have to lie motionless for quite a little time. It is now that Rachel, the character that gives her name to the title of this drama, appears. She is the mother of one of the Innocents and has a long lamentation over the dead body of one of the boys. This is undoubtedly one of the greatest moments of Twelfth Century Opera. To call it "liturgical drama" is obviously beside the mark. Rachel begins in a low key but her lamentation rises to an almost hysteric height then finally sinks away in resignation. It is plain opera on a line with Monteverdi’s Lament of Ariadne though indeed more tragic and concise. The Comforters try to pacify Rachel only succeed in stirring her up. They have not lost a son as she has, and it may be a very serious matter for a woman in her last years to lose her male support. When Rachel leaves, the Angel brings the boys to life again and they march out singing their last piece. But Rachel’s lament has left its mark at any rate on every woman in the audience. In order to give performances of these great dramas we realised that we should have to form a Society capable of doing so. My young friend, Brian Davis, was at Cambridge at the time and among his friends and my own there seemed considerable support for such a project. We found an excellent producer in Thor Pierres, who has been with us ever since and seems never floored by the peculiarities of structure of any church. He is still producing these music dramas some years later. He also designed the costumes. Our first full production of the Easter Trilogy was given at Edington Priory Church, Westbury Wilts, as part of their Music Festival. Thereafter we gave performances of the Easter dramas in the City Churches, e.g. St. Helen’s Bishopsgate, in the suburbs, e.g. St. Mary’s Finchley, and as far afield as Exeter, Chester and Iffley and also in Southwark Cathedral. We gave performances of the Christmas Dramas wherever we could find an available school for the boys. For example there was one at Hastings. At Offham we had boys from Crawley. We had the "communists", as the scholars from King’s College called them. They may have been "commoners" but they were a very good choir of boys. At Winchester College, we had their Choristers. For many years, we were supported by The Revd. Ian Smith and the choirboys from St Peter’s Crawley, who also made recordings. The three Maries who served us so well for many years were Pamela Lewis (Third Mary and Mary Magdalene), Maire Lynch (Second Mary), Nina Andrews and Alice Wakefield. The Angel who sang the beautiful long recitative at the beginning of The Shepherds and whom I left completely unaccompanied was Clementia Raikes. The male Angel who had a Recit. and Arietta answering the Three Maries was Christopher Wilson and later William Leigh Knight. Our best Herod and Doubting Thomas was Donald Francke, George Neighbour was a notable Shepherd and St. John, and an excellent Knight was Michael Chattin. The man whom we relied on to take the difficult part of the Saviour until he went to Canada was Tony Petti. For many years Michael Channon led the procession of the Te Deum round the Church. Among my small orchestra I remember specially Audrey Twine who never seemed to tire of holding long notes on the viola, Helena Morcom Taylor on her Celtic harp, Dorothy Southern at the organ, Derek McLean and Edgar Gordon who appeared as shepherds and then took their places with their recorders. Edgar and Thor shared the conducting. I conducted and organised the performances while my wife acted as wardrobe mistress with help from others for the first twenty-five years or so. The Society is now under the direction of Miss Maire Lynch, who, for a long period has been giving so much time and thought to these productions. Edgar Gordon also does much to keep the Society going and organises the orchestra. It is not possible to mention all the people who have given so much over the past thirty-five years but these are some of their names: Chris Davies and John Morgan as the Saviour, Robert Moberly, Rose Edgcumbe, Christina Gates, Nanette Simmons, Lynette Barling, Joy Manners, Yvonne Fisher. Incidentally Nina Andrews and Rose Edgcumbe many years ago sang in my operas.

|