Salmanov Reference

http://home.wanadoo.nl/ovar/salmanov.htm

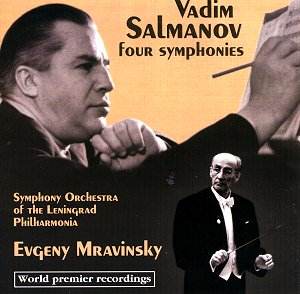

The Russian composer

Vadim Nikolayevich Salmanov was born

on 4 November 1912 in St. Petersburg

and died there on 27 February 1978.

After piano studies with his father

he took theory lessons from Akimenko

then moved to the Leningrad Conservatory

where from 1936 until 1941 his compositions

lessons were taken with Mikhail Gnessin.

He joined the staff of the Conservatory’s

composition department in 1947 and remained

there in various capacities until his

death. Music had not always been the

most natural choice for him. He pursued

a career in geology up until 1936.

Salmanov's four symphonies

are each about thirty minutes long.

The four symphonies are represented

here by recordings taken from concert

performances; in many cases presumably

the concert premieres. In each case

the symphony was premiered by the Leningrad

Philharmonic conducted by Evgeny Mravinsky.

The First Symphony:

The opening is reminiscent of the music

for the Teutonic knights in Prokofiev's

Alexander Nevsky mixed with hushed

and etiolated mystery - to return in

the second movement - and lyrical inspirations

reminiscent of Miaskovsky's Fifth and

Sixth Symphonies. Its finale has one

of those scuttling, conspiratorial tense

chases part recalling Bruckner's Romantic

but at 00.46 it soon picks up on

the cavalry charge élan of Miaskovsky.

Here is a symphony not immune from rodomontade

(III 2:03) but clearly more in sympathy

with people like Boiko in the USSR and

George Lloyd in the UK than with true

originals like Shostakovich. The sound

is about 46 years old but apart from

a certain warbly quality is quite acceptable.

The echt Russian brass is evident in

the trumpets (III 4:56).

Three years later and

we get the Second Symphony which

opens in plaintive melancholy with flute,

clarinet and oboe, chilly if not bleak.

The second movement Summons of Nature

is packed with fast-darting detail

recalling a Prokofiev scherzo ballet

movement. Pealing stratospheric violins

trade gestures with minatory brass the

national identity of which is never

in doubt (IV 3:17).

As many years separate

the Third and Second symphonies

as divide the first two. However Salmanov's

four movement Third flirts with a medley

of dodecaphony and tonality. The posturing

of the first movement is unconvincing

but the modest Andante with its

sighing dissonances is more substantial

fare. There is a scarifying goblins'

scherzo in the shape of the allegro

vivace. Salmanov is often better

with gentle canorial ideas. With a Bergian

tinge this lyricism returns for the

Andante non troppo finale which

ends ominously. The Cold War had perhaps

taken its toll. For all that Salmanov

was seen as a loyal apparatchik and

has been bracketed with Khrennikov this

symphony ends without staged heroics

and fluttering banners.

His Fourth last

symphony came in 1977. It has been dubbed

by Salmanov researcher Mark Aranovsky,

a ‘farewell symphony’. Salmanov died

at the age of 66, one year later but

was present at the premiere. Aranovsky

speaks of 'its understated beauty, woven

from the same delicate colours as the

Leningrad sky during a summer sunset.'

Across three movements, of which the

first is almost as long as the other

two put together, Salmanov presents

three contrasted portraits. The second

movement Marciale is a knockabout

romp rife with toytown fanfares and

scathing Shostakovichian assaults. It's

an enigmatic presence when flanked by

what seem to be two musing eclogues

alive with touching soloistic gestures

from woodwind and solo violin. In the

final andante this reflective

material is matched up to strivingly

impassioned music at times torn by the

strife we hear in the first movement

of Shostakovich 6. However it is in

the cool Miaskovskian elegiac birdsong

of the flute at 5:42 that we glimpse

what is I think the real Salmanov.

These recordings are

far from hi-fi but are of fair to middling

broadcast quality given their provenance.

If you enjoy exploration there are rewarding

works here. Of the four only the Third

strikes me as lame and ill-sorted. The

Fourth fascinates in its elegiac outer

movements; the breathing of the violins

at 8:44 in the finale remains a fine

inspiration.

It's a pity that the

liner-notes tells us so little about

Salmanov. While these may be world premiere

recordings this is not the first time

they have been issued.

Salmanov may have thumped

the tub at times but his symphonies

were more often rounded with a curve

into serenity than a thundering bombastic

call-to-arms.

Rob Barnett