|

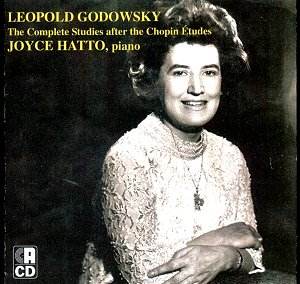

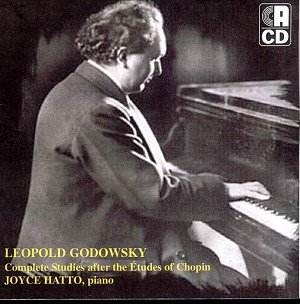

These discs have been

withdrawn from sale as they may not feature

Joyce Hatto after all.

They are thought to be performed by Carlo Grante

from the Altarus label

|

Leopold

GODOWSKY (1870-1938)

The Complete Studies on Chopin’s Etudes

1. No. 1, Op. 10 No. 1 (1st version), C major

[2'09]

2. No. 2, Op. 10 No. 1 (2nd version), D flat

major, left hand [2'59]

3. No. 3, Op. 10 No. 2 (1st version), A minor,

left hand [1'40]

4. No. 4, Op. 10 No. 2 (2nd version), A minor,

'Ignis fatuus' [2'01]

5. No. 5, Op. 10 No. 3, D flat major, left hand

[4'47]

6. No. 6, Op. 10 No. 4, C sharp minor, left

hand [2'42]

7. No. 7, Op. 10 No. 5 (1st version), G flat

major [1'43]

8. No. 8, Op. 10 No. 5 (2nd version), C major

[1'59]

9. No. 9, Op. 10 No. 5 (3rd version), A minor,

'Tarantella' [2'30]

10. No. 10, Op. 10 No. 5 (4th version), A major,

'Capriccio' [2'11]

11. No. 11, Op. 10 No. 5 (5th version), G flat

major [2'00]

12. No. 12, Op. 10 No. 5 (6th version), G flat

major [1'52]

13. No. 12a, Op. 10 No. 5 (7th version), G flat

major, left hand [2'30]

14. No. 13, Op. 10 No. 6, E flat minor, left

hand [3'37]

15. No. 14, Op. 10 No. 7 (1st version), C major,

'Toccata' [1'57]

16. No. 15, Op. 10 No. 7 (2nd version), G flat

major, 'Nocturne' [3'17]

17. No. 15a, Op. 10 No. 7 (3rd version), E flat

major, left hand [2'22]

18. No. 16, Op. 10 No. 8 (1st version), F major

[3'18]

19. No. 16a, Op. 10 No. 8 (2nd version), G flat

major, left hand [3'56]

20. No. 17, Op. 10 No. 9 (1st version), C sharp

minor [2'56]

21. No. 18, Op. 10 No. 9 (2nd version), F minor,

Imitation of Op. 25 No. 2 [3'04]

22. No. 18a, Op. 10 No. 9 (3rd version), F sharp

minor, left hand [6'11]

23. No. 19, Op. 10 No. 10 (1st version), D major

[4'39]

24. No. 20, Op. 10 No. 10 (2nd version), A flat

major, left hand [2'38]

25. No. 21, Op. 10 No. 11, A major, left hand

[3'18]

26. No. 22, Op. 10 No. 12, C sharp minor, left

hand [3'11]

27. No. 23, Op. 25 No. 1 (1st version), A flat

major, left hand [3'06]

Joyce Hatto (piano)

Joyce Hatto (piano)

Rec. The Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge,

4th September and 10th

October 2004

CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO RECORDINGS CACD 9147-2

[79.00]

CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO RECORDINGS CACD 9147-2

[79.00]

1. No. 24, Op. 25 No. 1 (2nd version), A flat

major, like a piece for 4 hands [2'36]

2. No. 25, Op. 25 No. 1 (3rd version), A flat

major [2'56]

3. No. 26, Op. 25 No. 2 (1st version), F minor

[3.43]

4. No. 27, Op. 25 No. 2 (2nd version), F minor,

'Waltz' [2'33]

5. No. 28, Op. 25 No. 2 (3rd version - A), F

minor [2'32]

6. No. 28, Op. 25 No. 2 (3rd version - B), F

minor [2'46]

7. No. 28a, Op. 25 No. 2 (4th version), F sharp

minor, left hand [2'38]

8. No. 29, Op. 25 No. 3 (1st version), F major

[2'22]

9. No. 30, Op. 25 No. 3 (2nd version), F major,

left hand [2'30]

10. No. 31, Op. 25 No. 4 (1st version), A minor,

left hand [2'13]

11. No. 32, Op. 25 No. 4 (2nd version), F minor,

'Polonaise' [6'13]

12. No. 33, Op. 25 No. 5 (1st version), E minor

[3'34]

13. No. 34, Op. 25 No. 5 (2nd version), C sharp

minor, 'Mazurka' [2'42]

14. No. 35, Op. 25 No. 5 (3rd version), B flat

minor, left hand [4'24]

15. No. 36, Op. 25 No. 6, G sharp minor [2'20]

16. No. 38, Op. 25 No. 8, D flat major [1'25]

17. No. 39, Op. 25 No. 9 (1st version), G flat

major [0'59]

18. No. 40, Op. 25 No. 9 (2nd version), G flat

major, left hand [1'24]

19. No. 41, Op. 25 No. 10, B minor, left hand

[4'25]

20. No. 42, Op. 25 No. 11, A minor [4'33]

21. No. 43, Op. 25 No. 12, C sharp minor, left

hand [3'21]

22. No. 44, Méth. M-F No. 1, F minor,

left hand Moscheles 1 [1'33]

23. No. 45, Méth. M-F No. 2 (1st version),

E major Moscheles 2 First Version [4'04]

24. No. 45a, Méth. M-F No. 2 (2nd version),

D flat major, left hand Moscheles 2 Second

Version [2'03]

25. No. 46, Méth. M-F No. 3, G major

'Menuetto' Moscheles 3 Sole Version [3'45]

26. No. 47, Op. 10 No. 5 and Op. 25 No. 9, G

flat major, 'Badinage', 2 studies combined [1'39]

27. No. 48 Op. 10 No. 11 and Op. 25 No. 3, F

major, 2 studies combined [3'29]

Joyce Hatto (piano)

Joyce Hatto (piano)

Rec. The Concert Artist Studios, Cambridge,

1st September and 10th and 11th October

2004

CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO RECORDINGS CACD 9148-2

[77.58]

CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO RECORDINGS CACD 9148-2

[77.58]

|

Error processing SSI file

|