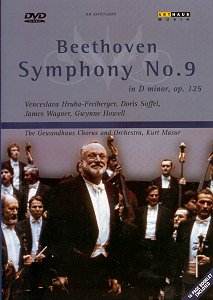

As the only currently available version of Beethovenís

Ninth in this format and as the document of one of the more enduring

conductor-orchestra relationships during the last half-century, this

DVD would appear to hold a certain amount of interest. After Masur's

quarter of a century as chief conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra,

its members are evidently adept at translating the batonless jerks,

punches and sweeps which constitute his conducting style, for they respond

to his gestures with a precision which verges on the uncanny. Masur

stands isolated on his podium, a good ten feet away from the front desks

of strings, sometimes glaring at them, sometimes staring into space

and perhaps hearing his own Beethoven Nine in his head (contemporary

accounts suggest that the composer did the very much same at the first

performance). I hope it was more interesting than the one on this disc.

The first movementís opening tremolos over bare fifths,

which Furtwängler likened to the very process of Creation, are

heard over a screen shot of the scoreís first page. What you hear is

as prosaic as what you see: bare fifths, no sense of tension at the

impending tutti irruption which will give form to those fifths. It sets

the scene ideally for a performance which apparently seeks to minimise

conflict and to promote tonal beauty and uncomplicated flow. The orchestra

has a communal ownership of a seamless legato, the cultivation of which

has often been thought a conductorís greatest achievement (herein lies

the root of Karajanís success with the Berlin Philharmonic). Thereís

no reason I can see why a beautiful noise should preclude the achievement

of a thoughtful and distinctive interpretation, yet it does so here.

Tempi rarely vary from a sensible mean between the Romantic styles of

old and the metronome marks adopted by those who attempt to follow the

composerís, though they tend more towards the former. Too often - in

fact, nearly all the time - one note follows another for concert-hall

convention rather than any felt sense of inner logic or struggle - qualities

which the work manifests in every bar. Lack of consistency undermines

the former and lack of drama precludes the latter.

A couple of examples: when Masur has allowed very little

relaxation during the slow movement, the ritenuto he applies to its

last note strikes a note not only false but pointless. During the course

of the movement he has relied on the stringsí potential for cantabile

playing, which they deliver but with remarkably little sense of how

special this music is: I wonder if they would treat the first fiddle

part of a late quartet in the same, blithe way. Likewise, I canít see

or hear any justification for the timpanist to play his four offbeat

interjections in the Scherzoís second half (which is unrepeated) so

that each is successively quieter than the last. The first is marked

forte; no diminuendo is marked, and none makes sense, for each is a

rip in the seamless threads of quavers in the violins, not a part of

the same fabric as Masur treats it. Yet the horns which should gradually

gain prominence at the start of the Scherzo proper are denied their

marked crescendo. The tutti outburst which should silence them thus

dissipates no tension, for none has been generated.

The last movement's soloists are well-matched and the

choir well-drilled; this is not really enough to characterise Schiller's

aggressive text, alternately beseeching, fist-waving and exalting, but

it accords with Masur's conception as a whole. It leaves me in no better

position than the baffled critic of the Wiener allgemeine Theater-Zeitung,

who on May 13 reported of the premiere six days earlier, 'After hearing

one of these immense compositions, one can scarcely say more than that

he has heard them.'

Peter Quantrill

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews