|

|

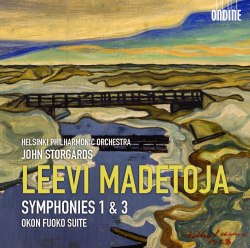

Leevi MADETOJA (1887-1947)

Symphony No. 1 in F Major, Op. 29 (1914-1916) [21:13]

Symphony No. 3 in A Major, Op. 55 (1925) [31:24]

Okon Fuoko Suite, Op. 58 (1930) [13:40]

Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/John Storgårds

rec. 19, 22-23 April 2013, Helsinki Music Centre, Helsinki, Finland

ONDINE ODE 1211-2 [66:39]

‘Just the kind of second-rate music I like to hear,’

remarked a musician friend when I mentioned Madetoja. That’s

not as damning or as flippant as it sounds, for music written deep

in the shadow of more illustrious contemporaries can be very rewarding

indeed. That’s certainly true of the Finnish composer Leevi

Madetoja, forced to find his foothold in a musical landscape so completely

dominated by Jean Sibelius. Even though the latter’s bold, striding

presence is clearly discernible in Madetoja’s three symphonies

and Kullervo that’s no reason to dismiss these works

as ‘Sibelius-lite’. Once I was tempted to do just that,

only to discover how short-sighted I’d been.

As so often it comes down to the passion and advocacy of musicians

and the support of an adventurous record label. Indeed, it was conductor

Petri Sakari and Chandos’s 1991-1992 recordings of Madetoja’s

orchestral music - with the Iceland Symphony - that revealed just

how distinctive and interesting this composer’s voice really

is. Now we have John Storgårds, who first came to my attention

with a performance of Kalevi Aho’s mighty Luosto Symphony

(review).

At last year's Proms he and the BBC Philharmonic gave us a fine Korngold

Symphony in F sharp; there's also a keenly awaited cycle of Sibelius

symphonies, also with the BBC Phil (Chandos CHAN10809).

Clearly Storgårds is a maestro to watch; as for the Helsinki

Philharmonic - heard to great advantage in their recent all-Shostakovich

disc with Vladimir Ashkenazy - they are grabbing headlines too (review).

This confluence of talents should make for a compelling Madetoja cycle,

the first instalment of which was warmly welcomed Michael Cookson

(review).

Technically these Ondine releases are also a cut above; in fact that’s

partly why I chose one of their Rautavaara discs as my Recording

of the Year 2013 (review).

Madetoja recordings may not be two a penny, but the pioneering Sakari

set is well worth the few shekels it costs. These are eloquent and

thoughtful readings, well played and captured in vintage Chandos sound;

in short, this is a collection to cherish (review).

Sakari’s are the sort of proselytizing performances that drag

this music out of the inhibiting shadows and into the light. Yes,

these discs really are that good; given such a distinguished

precedent Storgårds and his Helsinki band really do need to

be at their peak.

The First Symphony gets a most ardent outing here; Storgårds

is bold and incisive in the Allegro and those wistful harp

tunes are delectably done. Ondine’s recording is just as forthright,

yet it remains warm and spacious throughout. The dark, brooding Lento

misterioso conjures the spirit of Sibelius from the sullen bedrock

only to morph into a landscape of its own design; now broad and imperious,

now light and lovely, this is memorable music that hides its relative

youth very well. The finale is no less arresting; Storgårds

ensures the heart of this symphony beats with a strong, steady pulse

- just listen to those mobile pizzicati - and he builds breath-taking

and craggy perorations at the close.

How does Sakari compare? He isn’t as impetuous in the outer

movements, but in mitigation there’s a security of utterance

that’s just astonishing for a composer under thirty. Sakari

nurtures the long spans, and that makes for a rapt, seamless reading;

Storgårds seizes the shorter ones and gives us a more urgent

and visceral view of this score. Both are very persuasive, which is

why I couldn’t possibly recommend one version over the other.

No, you must have both.

Madetoja’s Third Symphony, begun in France and completed in

Finland, wanders in a very different setting to that of the First.

Perhaps wanders isn’t the right word, for there’s nothing

aimless about this transparent and classically proportioned piece.

The opening Andantino is both graceful and gracious, especially

in Sakari’s firm but gentle grasp, and the Icelanders play with

a wonderful blend of ardour and inwardness throughout. The Adagio

is especially pliant, and Sakari’s lofty, far-sighted approach

brings with it an ease - an authority, if you will - that’s

deeply satisfying.

You might wonder why I defer so much to the Chandos recordings; well,

that’s how high the bar has been set. Storgårds and his

players vault it easily enough in the Andantino, albeit with

less of Sakari’s athleticism. As before Storgårds focuses

on the moment rather than the whole half hour, and while that has

its appeal I much prefer Sakari’s longer view. I suspect if

the audience at the work’s premiere had heard Storgårds

they would have been less perplexed by Madetoja’s stylistic

departures. Make no mistake this symphony isn’t remotely regressive,

and both conductors give it real character and shape.

Storgårds phrases the Adagio well enough, although his

reading - and Ondine’s more analytical recording - create stronger

contrasts and extend Madetoja’s colour palette. Such immediacy

is no bad thing - climactic moments are undeniably sonorous and thrilling

- but Sakari’s cooler, more cerebral approach has its virtues

too. That said, Storgårds trumps Sakari in the Allegro,

and the HPO respond to his demands with commendable alacrity and edge.

The finale, marked Pesante, dances darkly, its glorious bass

weight balanced by silken upper strings and chattering woodwinds.

It all ends with a series of imposing tuttis and a quiet, quirky sign-off.

Madetoja only managed to create one of the three projected suites

from his ballet- pantomime Okon Fuoko (the ballet can be heard

in full on Alba).

Based on a conceit familiar from 19th-century French ballet it tells

the story of a Japanese doll-maker and his come-to-life creation Umegave.

The original work didn’t do well at its premiere in 1930, which

critics insist had less to do with the music than the libretto. I

have to state an outright preference for Sakari’s performance

which, from its frisson-inducing start, has a theatrical heat

and hum that simply eludes Storgårds and his orchestra. Frankly,

the latter seem more than a little foursquare and rather rustic alongside

the suave, metropolitan Sakari. The colourful Chandos recording -

which is sensational in the tuttis - is just as subtle and sophisticated

too.

That pretty much sums up my response to these performances; Sakari

is elegant and refined - a perfect summation, perhaps, of Madetoja’s

studies in various European capitals - while Storgårds’

scruff-of-the-neck readings should win new friends for composer and

conductor alike. For that reason the Ondine disc is an ideal starting

point for those who wish to explore Madetoja’s œuvre.

Following that up with the Sakari set - a well-filled and very tempting

bargain - will deepen one’s affection for this music and banish

all doubts about its range and quality.

Fine performances of these two symphonies; Storgårds’

Okon Fuoko is no match for Sakari’s though.

Dan Morgan

http://twitter.com/mahlerei

|

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews