|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

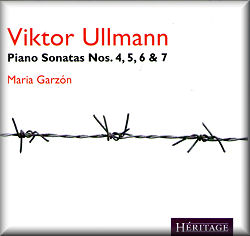

Viktor ULLMANN (1898-1944)

Piano Sonata No.4, op.38 [20:06]

Piano Sonata No.5, op.45 [17:53]

Piano Sonata No.6, op.49 [13:47]

Piano sonata No.7 [24:33] (Á mes enfants Max, Jean, Felice)

Maria Garzón (piano)

rec. Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, UK, October 2012.

HÉRITAGE HTGCD 246 [76:28]

It is extremely pleasing to note the increasing number of records being

released in recent years that have showcased music by that lost generation

of composers who perished at the hands of the Nazis; Viktor Ullmann was

numbered amongst them. Whilst much of what he wrote has been lost a goodly

amount has survived including most of the 23 works he wrote while incarcerated

in Terezin (Theresienstadt) the transit camp from whence he was dispatched

to the gas chambers in Aushwitz. Sonatas 5, 6 and 7 were all composed

in Terezin while the fourth was composed the year before he was sent there.

The more music by Viktor Ullmann I hear the more I am struck by a feeling

of loss at the thought of such a talent being extinguished. Alice Herz-Sommer,

a Prague-based Jewish pianist, who was also sent to Terezin, and who miraculously

survived the holocaust, has appeared in several documentaries about those

fearful times. She is the dedicatee of the fourth piano sonata and has

always been a champion of Ullmann’s music. The sonata’s first movement

is dominated by spiky rhythms reminiscent of Bartók but despite this there

is an overall sense of gentle playfulness that at times is quite dreamy,

particularly in its closing passages. The second movement also opens in

a similar vein before taking on a more serious note which is hardly surprising

given that it was composed in 1941 when good news was in extremely short

supply. The music becomes increasingly anxious as the movement continues.

It ends on a sad note. The third movement begins in classical style that

is almost Bachian and this element dominates throughout. The sonata finishes

with a flourish.

The fifth sonata Ullmann dedicated to his wife Elizabeth who died soon

after their arrival in the camp. It is hard to imagine the despair this

little family must have experienced with Ullmann trying desperately to

keep busy composing while looking after and consoling his four young children

who were with him in such appalling circumstances. There is no especial

feeling of sadness expressed in this sonata’s opening movement - on the

contrary it is quite gay in spirit. The second movement, however, is considerably

darker in mood and this intense emotion is fully explored though he refuses

to remain this way. He pulls himself up from the depths of despair with

a brisk and humorous Toccatina whose delightful little tune bubbles

along for its all too brief 47 seconds. This then leads to a Serenade

which mixes caprice with a tinge of sad reflection. Some moments sound

very like Debussy. The sonata finishes with a busy Fugato that

ends on an upbeat note.

Ullmann’s sixth piano sonata is an example of his exploration of jazz.

This was a common feature among composers at the time. It was written

for Edith Kraus who played it many times in the camp and who became another

champion of his music. She also managed to survive the horrors that befell

them all. It is charming and delightful and while the first movement has

an extremely poignant ending the overriding atmosphere is one of joy and

fun. Given its birthplace, this is further testimony to the huge resolve

Ullmann had. It enabled him to control his emotions and subjugate them

to serve his music.

The seventh and last of Ullmann’s piano sonatas is the longest of his

compositions in this genre. It is almost akin to a musical autobiography

in which he quotes his obvious loves in the shape of quotations and allusions

to such composers as Bach, Mahler, Schoenberg and Wagner. Into this mix

he adds echoes of Slovak hymns, Lutheran chorales and even a Hebrew folksong

that informs the final movement. The booklet notes correctly attribute

Ullmann’s dedication of this sonata to three of his children Max, Jean

and Felice (Pavel, born in 1940 had already died in the camp). The track

listings mistakenly give it as being for the 5th. Jean and

Felice were sent to England via Sweden on one of the kindertransports

and survived. Max died in Auschwitz along with his father. The sonata

is a wonderful tribute to life and its final movement cleverly fuses a

Hebrew song with strains of the Slovak National anthem, a Hussite song,

J. Cruger’s hymn “Now thank we all our God”, the name of B-A-C-H and even

an allusion to Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde in its glorious closing

bars. What a final declaration on life this last composition is. It so

eloquently illustrates Ullmann’s statement concerning his time in Terezin

that "By no means did we sit weeping on the banks of the waters of

Babylon. Our endeavour with respect to arts was commensurate with our

will to live." It is all the more heartrending to listen to when

you know the back-story.

Spanish pianist Maria Garzón dedicated the disc to Alice Herz-Sommer and

Edith Kraus. It also carries an in memoriam to Jeanne Mckintosh, a member

of the resistance tortured and murdered by the Nazis. Garzón plays all

four of these valuable works with obvious reverence allowing the music

to sing out and weave its spell. It’s a fitting tribute to a man who found,

even in the direst circumstances of life in Terezin, a spirit that refused

to be extinguished. Somehow he managed to harness the strictures of camp

life to his creative will. I commend this disc to any admirer of Ullmann

and the other composers who perished in the holocaust.

Steve Arloff

|