|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

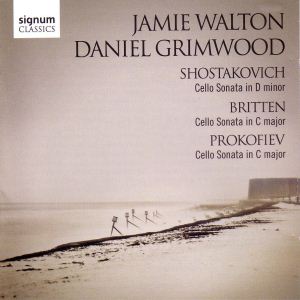

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Cello Sonata in D minor, Op. 40 (1934) [26:29]

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

Cello Sonata in C major, Op. 65 (1961) [18:39]

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Cello Sonata in C major, Op, 119 (1949) [22:15]

Jamie Walton (cello); Daniel Grimwood (piano)

Jamie Walton (cello); Daniel Grimwood (piano)

rec. 16-18 February 2011, Wyastone Leys Concert Hall, Monmouthshire,

Wales

SIGNUM CLASSICS SIGCD274 [67:26]

SIGNUM CLASSICS SIGCD274 [67:26]

|

|

|

Even if Shostakovich the symphonist had barely begun to emerge,

he nonetheless had several masterworks to his credit in 1934

when he composed his Cello Sonata. One of these was the opera

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, the work that provoked

Stalin’s disapproval, propelling the composer into years

of artistic limbo. The sonata is in four movements, and although

the overall tone is more lyrical and genial than we associate

with this composer, the minor key close of the first movement

is not the only passage to feature the typical Shostakovich

combination of sardonic humour and near-despair. The second

movement is a ferocious scherzo - Jamie Walton tears into this

in impressive fashion - but the passionate, deeply felt slow

movement is the heart of the work. There are many rival versions

of this sonata. I particularly admire the robust and dramatic

reading from Han-Na Chang and Antonio Pappano, a not particularly

generous coupling on EMI of her outstanding performance of the

First Cello Concerto. The slow movement of the present performance

seems underplayed when compared to Chang, and the reading as

a whole is richer and more mellow. I wasn’t totally convinced

at first, but on subsequent hearings I’ve happily come

round to Walton’s and Grimwood’s view of the work.

Prokofiev composed his Cello Sonata for Mstislav Rostropovich,

who gave the first performance in 1950, with Richter, no less,

at the piano. The pianist tells the story of playing it to two

different judging panels, apparently for authorisation to give

the work in public. I wonder if present-day artists in the free

world can really imagine what it is like to work under such

conditions. There was perhaps relatively little official opposition

to this sonata, as it is a predominantly lyrical work, with

none of the harmonic daring associated with the younger composer.

The first impression the work gives is a carefree one, but subsequent

listening reveals much more. The work is beautifully written

for the two instruments; the composer clearly wanted to exploit

the cellist’s sound in the low register. The first movement

is a fine example of Prokofiev’s gift for melody, with

an amusing passage where the two instruments imitate each other,

and a poignant, chiming close. Even the wittily ironic second

movement scherzo has a more lyrical interlude and the energetic

finale has a surprisingly dramatic finish.

Britten was introduced to Rostropovich by Shostakovich at the

first British performance of the latter’s First Cello

Concerto, and their friendship endured until the composer’s

death in 1976. The Cello Sonata was the first of five works

that Britten composed for Rostropovich. The most concentrated

of the three works on this disc, its five movements are over

and done with in less than twenty minutes. A motif of only two

notes makes up most of the thematic material of the first movement.

Wistful in mood for much of its length, and often touchingly

lyrical, it also features passages more powerful and overtly

demonstrative than is usual from this composer. The second movement

is a nocturnal scherzo whose pizzicato writing could almost

have come from Bartók’s pen. An expressive, melancholy

slow movement follows, then a weird march, and the work ends

with a fearsome moto perpetuo. The cellist’s wife,

Galina Vishnevskaya, apparently found the work to be a portrait

of her husband’s wildly changing moods. This may be so,

but there is a certain greyness about the writing too, and one

is left at the end of the work not quite sure what the composer

was aiming at.

Cellists hoping for a place on the world stage all have the

same cross to bear, and that is the inevitable comparison with

Rostropovich. If they are wise, they learn from him whilst forging

their own sound and personality. The only time I ever saw him

in concert he played with a barely controlled frenzy that bordered

on the demented. Jamie Walton’s playing is several degrees

cooler than this, and this shows in the performance of the Britten.

Yet whilst Rostropovich’s performance, with Britten at

the piano, is indispensable in any Britten collection, this

performance is just as fine in its own way. Walton’s sound

is gorgeous, as is that of Daniel Grimwood, made evident in

the rich and immediate Signum recording. Both players are technically

flawless, play with the utmost musical intelligence and sensitivity,

and are totally at one in all three works.

The magnificent Dutch cellist Peter Wispelwey has exactly this

programme on a well-received Channel Classics CD. I have not

heard it, but it is hard to imagine how it can surpass this

outstanding disc.

William Hedley

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews