|

|

SEIBER’S JOYCE CANTATAS

by Alan Gibbs

The Mátyás Seiber Trust is marking the anniversary of the composer’s

tragic death in September 1960 by fostering performances and

recordings of his music, the first of the latter being the Delphian

CD of the three string quartets already reviewed

by MusicWeb International .

Now it is hoped that the first-ever commercial recording of

his choral masterpiece, Ulysses (1946-7) will soon follow,

coupled with the later Joyce cantata, Three Fragments from

‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’ (1957). A favourite

among Kodály’s famous group of progressive students at Budapest,

Seiber went on to teach in Frankfurt and to play his ’cello

in the Lenzewski Quartet (he had previously played in a ship’s

orchestra).

His enquiring mind enabled him to gain familiarity with a variety

of musical styles including jazz (in which he founded the first

class dedicated to its theory and practice), accordion technique,

choral settings and arrangements of folksongs of Hungary, Yugoslavia

and elsewhere, and wrote a song which won an Ivor Novello award.

But he was especially drawn to the compositional advances of

the 1920s, notably twelve-note technique, which he adopted in

the Second Quartet (1934-5) and many other works, with varying

degrees of freedom. In 1935, having joined the exodus of artists

during the rise of Nazism, he settled in England, as did the

likes of Gerhard and Wellesz. He was not impressed with our

insularity and the conservatism of our academic institutions,

believing that ‘the teaching of composition should be based

on the actual practice of the masters past and present’.1

Fortunately Morley College followed an independent line established

by Holst and developed by Michael Tippett, who invited Seiber

to join the staff in 1942. He became a much sought-after teacher

of composition, and the premičre of Ulysses on 27 May

1949, at a Morley concert in the Central Hall, Westminster (the

rebuilt college was not opened until 1958), conducted by Walter

Goehr with Richard Lewis as soloist, was a landmark in his acceptance

as a British composer.2

The poetry of James Joyce attracted musical settings and the

Joyce Book of 1932 featured thirteen composers, not only

of Irish descent or sympathies like Moeran and Bax, but others

like the American George Antheil, a personal friend. He even

offered to write a libretto for Antheil, who embarked on an

opera, Mr Bloom and the Cyclops, but never finished it,

and Seiber’s Ulysses made history as the first setting

of Joyce prose to attain performance. Seiber’s musical versatility

was matched by his facility in learning languages, and when

I suggested to his daughter Julia that Joycean prose would be

a formidable obstacle to a Hungarian, she replied ‘Language

is no barrier to a multi-linguist!’ Even he admitted that he

found the book ‘rather hard going at first’3, but

he was won over by ‘its symbolism, …its marked capture and expression

of the totality of human experience, …the formal aspect of its

construction, the verbal virtuosity, the relevance of certain

recurring motives which reminded me of musical composition’.

The parodies in the text, which include a drama (Circe) and

newspaper paragraphs (Aeolus), even boast a ‘fuga per canonem’

(Sirens), but it was a passage in Ithaca that Seiber ‘simply

had to set to music –I have not felt such strong compulsion

ever before or after’. Mosco Carner4 joined the chorus

of critics who felt that ‘the text …might almost have stepped

out of a text-book on natural science’ and Michael Graubart

maintains that Seiber failed to detect the satire at its heart.

Certainly the question and answer immediately preceding this

‘mathematical catechism’ hardly prepares us: ‘For what creature

was the door of egress a door of ingress? For a cat.’ Then Bloom,

whose enthusiasm for astronomy was evident when he pointed out

the stars and constellations to Chris Callihan and the jarvey,

suddenly expatiates on the universe to Stephen. Joyce, who observed

classical unities of place and time in the book –Dublin on 16

June 1904- was equally meticulous in quoting astronomical data

and street localities as known at the time. Yet this passage,

sheer poetry jostling with sober facts, was the author’s favourite

in the whole book, satirical or not, as Seiber discovered only

afterwards, pointing to an affinity in their cast of mind.

The composer abridged it to a more manageable length; there

are, in fact, many more omissions than are shown by the dots

in the text printed at the beginning of the vocal score.

Listeners who admit to being what Hans Keller called ‘twelve-tone

deaf’ when it comes to serialism may take comfort from the fact

that it is only partly serial: ‘I consider it essentially as

tonally conceived’ with key centres of the five movements E,

A, E, B, E as if conventional tonic, subdominant and dominant.

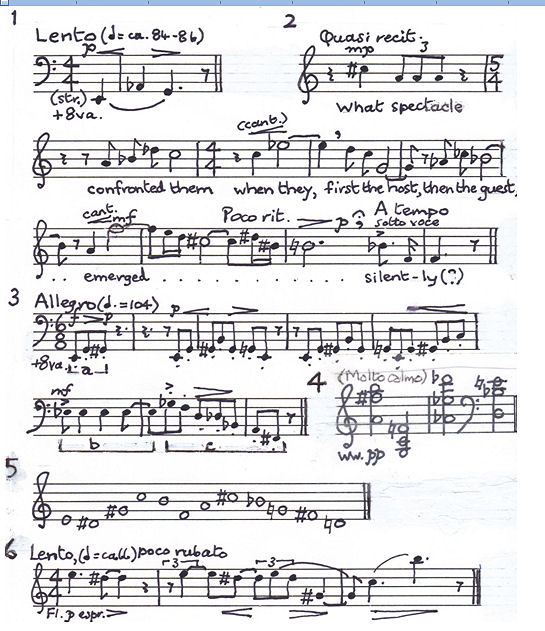

The first, The Heaventree, opens with a three-note motive

for bass strings (Ex 1). This generates the material of the

whole cantata. It is answered by its inversion in two-part counterpoint

typical of its composer, until a dark, dissonant minor triad

on trombones sets the stage for the tenor soloist’s entry (Ex

2). The word-setting is faithful to the language, unlike Stravinsky’s,

and true to the Purcell tradition rediscovered by Holst, Britten

and Tippett (in his case literally, Holst’s Purcell Society

volumes lying in the wreckage of the Morley bombing). The chorus

answers the question in a phrase rich in its own music: ‘The

heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit’. The thirds

(minor/major) of Ex 1 multiply in a rising and falling vocalisation

on ‘ah’, the shape of the phrase suggesting that of a tree and

the harmony surprisingly ‘English’. This impression is reinforced

by the Holstian procession of triads in brass and bassoons.

A semitone glissando shift on horns ushers in a brief interlude

mounting to a high E on a solitary violin.

Meditations of Evolution increasingly vaster suggested

passacaglia form as ‘best suited to express the cumulative weight

of detail’. Trombone and tuba announce the ground, Purcellian

in its three-beat rhythm with the odd syncopation (Purcell was

a favourite with Joyce, as it happens), and there is word-painting

to match, the chorus spreading out ‘vaster’, the sopranos spicily

‘scintillating’, softly-held chordal ‘distant’,, canonic ‘procession

of equinoxes’. An English-born composer might have been wary

of setting ‘new stars such as the Nova of 1901’ which risks

being a ‘stuffed owl’ moment, but it is swept along with ‘ten

lightyears’and ‘a hundred of our solar systems’ and the rest

towards an exciting fugal climax. ‘Our system plunging towards

the constellation of Hercules’ is portrayed with baroque graphicness.

This grows to a thrilling fourfold canon in the orchestra, sinking

to a quieter coda and contemplation of the comparative insignificance

of humanity’s lifespan. Sequential repetitions of the word ‘meditation’

close the movement.

Obverse meditations of Involution, a consideration of

the microcosmos as II had been of the bigger picture, consists

mainly of a fast 3-part fugue in scherzo style making demands

on chorus and orchestra alike. Ex 1 is rearranged and extended

into a twelve-note row of alternate minor thirds and semitones,

half ascending, the rest descending mirrorwise (Ex 3). Keller

noted a similarity in the row to that in Schoenberg’s Ode

to Napoleon (1942) 5: curiously, Seiber became

aware of this only on hearing the Schoenberg, then read Keller’s

article the next day. The significant elements are the three-note

motive a, the jazzy syncopations on one note (b)

and cascading tail (c) starting on a G flat promoted

in the order, strictly ‘incorrect’ but ‘the only thing that

interests me is whether I succeeded in writing some real music’.6

So much in the fugue defies prediction. The second and third

entries begin on different parts of the beat from the original

subject. A second exposition follows in which the parts, now

accompanying the voices, enter in reverse order. A contrary-motion

idea, heard instrumentally in the first episode, is associated

in the second with the words ‘microbes, germs, bacteria’,etc.

A third exposition inverts the subject, punching it out in piano

and xylophone, then trumpet, with the chorus divided into two

groups in octaves and woodwind and strings scurrying around

in semiquavers. In a slower, more lyrical interlude, the tenor

reflects on human elements until the excitement resumes, with

an entry of the subject in retrograde which you may not even

notice. A climax is reached in which martellato detached

chords punctuate a relentless ostinato based on c: the

debt to Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936)

is clear. A last exposition of three retrograde entries in the

bass, the first allocated to double bass only, is heard while

the chorus repeats the words ‘nought’, ‘nowhere’, ‘never’ in

whispers, and the bass strings disappear into a low pizzicato

E. Seiber once observed that Kodály’s orchestration, although

it might lack the brilliance of Ravel, always ‘came off’.7

His own in this movement is truly masterly.

Bartók is still in evidence in Nocturne-Intermezzo, although

the movement as a whole pays ‘HOMMAGE A SCHOENBERG’. Seiber

saw that two chords from that composer’s piano piece Op 19/1

could, in alternation, ‘embody that quietness and remoteness’

of solar and lunar eclipses which he wished to express. Perhaps

the two chords of Holst’s Saturn portraying old age were

at the back of his mind. He also noticed that Schoenberg’s could

be supplemented by two of his own, using up the remaining six

notes (Ex 4). Soon the woodwind is decorating two chords by

florid passages derived from the notes of the other two chords.

Then ‘taciturnity of winged creatures’ ushers in pointillistic

Bartókian night music, before the bleakness of the opening returns

for ‘pallor of human beings’.

The Epilogue begins with a wonderfully expressive eight-part

fugato on solo strings, descending slowly in pitch. Ex 1 has

been inverted and extended into a new twelve-note melody. The

chorus reflects with Bloom that ‘it was not a heaventree …it

was a Utopia’. We hear the original tree music, now hummed,

and the three-note motive returns in its inverted form, coming

to rest once again on that low E. One has to agree with Graham

Hair, in an online article,8 that Ulysses

‘ has not found the place in the repertoire of the typical British

choral society that it deserves.’

The year 1914, in which Joyce began Ulysses, saw the

completion of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,

with himself thinly disguised as the Stephen Dedalus character.

Seiber chose his Three Fragments from, respectively,

a poetic passage in which Stephen finds a harmony within him

matching the floating of clouds across the sky; his nightmarish

imaginings of the Last Judgment conjured up by Father Arnall’s

hellfire sermon; and his rapturous sleep on the beach, after

admiring a young girl bathing her legs in the water. This time

the chorus is wordless, the narration restricted to a spoken

voice (Peter Pears intended). Seiber indicates the relative

pitches of the words in Sprechgesang fashion, and requires the

chorus in general to sustain chords, humming or to a suitable

vowel (eg taking up the ‘oo’ of ‘moon’) or, more dramatically,

projecting the cries of the damned at the blowing of the Last

Trump. In between the two cantatas, Humphrey Searle had demonstrated

even greater courage in setting the last monologue of Anna Livia

Plurabelle (symbolizing the River Liffey) in Finnegan’s Wake,

in a cantata called The Riverrun (1951), which uses a

woman as speaker. (Even Seiber might have baulked at a text

beginning ‘Soft morning, city! Lap! I am leafy speafing, Lpf!’)

Just as Britten turned from the opulent scoring of Peter

Grimes to the more practical chamber group of The Rape

of Lucretia, so Seiber tailored his second Joyce cantata

to an even more modest ensemble in Three Fragments although,

like Britten, including piano and percussion –the latter giving

a choice of timbres. The influence of the younger composer may

perhaps be detected, eg in the association of bass clarinet

and sleep.

This is a thoroughly serial work, ‘about the strictest among

all my works to date’9: there is not a single note

which does not arise from the basic series (Ex 5). It is used

in all the regular permutations (ie including inversion, retrograde

and retrograde inversion) and sixteen transpositions (9 of the

basic row and 7 of its inversions). To those who claimed that

serialism was ‘abracadabra’, he replied that it was no more

obsessed with ‘the rules of the game’ than tonal composition,

and evolved organically from the actual creative process in

the same way10. In Three Fragments there is

a musical or literary reason for everything. Seiber held the

work in special affection, I think for two reasons: it is both

emotionally and intellectually satisfying; and it hides a personal

grief, the tragic death of his great friend Erich Itor Kahn

in New York, shortly before he began the work (now there

is an irony). The row contains his name ‘as an anagram’11:

as a Dorian Singer under Seiber I sang two of Kahn’s highly

individual Three Madrigals in a BBC recording of 24 April 1959,

not transmitted until 19 May 1960; the first began ‘Fare thee

well’. The row contains three semitones or major sevenths, with

all their expressive potential, and the ambiguous tritone, which

colours the harmony. The row is regularly divided into groups

of three and four, melodically and harmonically. It may already

have been noticed that the row of Ulysses, like those

of Webern’s string trio and quartet (and Searle’s The Riverrun)

contains six semitones. So would Seiber’s Concert Piece (1953-4),

and his rows often begin with a semitone, as here, dwelt on

lovingly by the flute in its opening phrase, to end in a complementary

seventh (Ex 6). The chorus takes it up in the tenors, then altos

and bass clarinet follow: we do not need to know that their

semitones come from different parts of the row, the music speaks

for itself. Seiber exploits the sustained notes of the vibraphone

as soon as the third bar, and they join high string chords,

with broken chords spread over the piano, to evoke Joyce’s ‘veiled

sunlight’. The choral harmonies give way to three-note imitative

phrases in different voices. And then comes pure magic: a beautiful

progression at the words ‘They [the clouds] were voyaging across

the deserts of the sky’ which proves, on analysis, to have a

subtlety of construction which is noteworthy, and is nothing

less than a modern application of the medieval technique of

isorhythm. A 3-chord phrase (color) is sung four times without

a break, but to a simultaneous rhythmic pattern (talea) which

occurs three times, not four, over the same period. The vibraphone

is providing a counterpoint using the same values but backwards,

and the piano is holding the whole together with flourishes

on the second and fourth beats of each bar. And, just by the

way, three different versions of the row are being employed

at the same time! I am quite sure that we (the Dorian Singers)

were totally unaware of all this as we sang and enjoyed these

five bars.. This is surely the art which conceals art. Seiber

would have been well aware of the historical precedent: Leonard

Isaacs observed ‘His own musical interests were so wide that

there was virtually no subject of music upon which one didn’t

find Seiber a mine of information’12. Antheil wrote

something similar of Joyce.13 The next passage, ‘He

heard a confused music’, prompts the composer to replay the

slow, mysterious trills of the nocturnal animals in Ulysses,

expanded here to six-note chords embracing all twelve notes,

and the voices enter and proceed at bewilderingly close intervals.

Successive phrases imitate each other, but in progressively

shorter values, then the process is inverted. But all this text-led

complexity gives way to the more tranquil texture of the opening,

and Joyce’s ‘one longdrawn calling note’, E (of course) is passed

from a group of six sopranos, reducing until a solitary unaccompanied

voice disappears into niente.

The hellfire second movement bursts upon us feroce, using

extreme intervals. Rooted in the tritone of E, B flat, among

its secrets are the first use of the tritone transposition (the

diabolus in musica –can this be a coincidence?) and serialism

of the rhythm. The latter is most obvious, perhaps, at ‘The

stars of heaven were falling’, where the repeated chords heard

in the previous two bars undergo a frenzied diminution, followed

by imitation at a mere semiquaver’s distance, to return later

in retrograde form. The timpani enter, repeating a 5-note rhythm

on a tritone, quietly at first, but louder with the appearance

of the Archangel Michael ‘glorious and terrible against the

sky’. (The diminutive James Blades, fresh from The Turn of

the Screw, is again brilliant here in my memory.) With no

brass available, the Last Trump is manufactured by the tutti

martellato with maracas and cymbal, culminating in bass

drum ff tutta forza. The frenzied opening

returns, to subside for the narrator to proclaim, with a note

of finality, ‘Time is, time was, but time shall be no more’.

Cymbal, small and large gongs take it in turns to break the

eerie silence.

Peaceful chords and a hauntingly persistent semitone E-F on

the vibraphone conjure up the ‘languor of sleep’ at the beginning

of the last movement.. In a 14-bar interlude major sevenths,

rising and falling, colour the choir’s contribution, but these

are no longer the extreme intervals of the previous movement,

of which nervous string tremolos are the only echo. At ‘His

eyelids trembled’ the vibraphone ostinato returns, now as a

descending semitone. Seiber still has surprises for us, though.

At ‘His soul was swooning into some new world’ the chorus hums

a melody, doubled now at the octave, now at the double octave,

now at the unison, until the row is complete. The nearest parallel

I can think of, if it be one, is the wonderful moment in Bach’s

Trauerode where the counterpoint gives way to an uncharacteristic

choral unison. Just before ‘Evening had fallen’ Ex 6 creeps

in on the ‘cello, with its semitone disguised as a seventh to

match the preceding texture. Before long the original version

returns in the choral tenors, to share in the discussion until

the semitone, repeated over and over, has the last word.

Ulysses has never been recorded, in spite of its success

all over Europe, including at the ISCM in June 1951. It was

performed at the Royal Festival Hall under Rudolf Schwarz in

1957 (BBCSO, Chorus and Choral Society, soloist Pears), and

again under him on 4 February 1961 in a live broadcast (BBCSO,

LP Choir, Morley College Choir, Dorian Singers, soloist Gerald

English). It is hoped to issue the first CD using the BBC recording

of a broadcast performance of 21 May 1972 under David Atherton

(LSO, BBC Chorus, soloist Alexander Young). Morley College featured

again with a performance on 19 March 2005 to mark the composer’s

centenary, by the Anton Bruckner Choir and the College Chamber

Choir and Chamber Orchestra under Christopher Dawe (soloist

Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts).

On 6 October 2010 an American SO concert under Leo Botstein

in Carnegie Hall will feature the cantata; Seiber’s daughter

Julia hopes to attend.

Three Fragments was performed at Basle in November 1958,

at Aldeburgh on 25 June 1959 (Richard Standen replacing an indisposed

Pears), and at the RBA Galleries on 11 December 1959. The first

broadcast was on 18 June 1959 (recorded on 28 May) and the only

commercial recording so far was issued by Decca in 1960, with

the Dorian Singers, Pears and the Melos Ensemble conducted by

the composer. It is hoped to reissue this very soon on a CD along

with Ulysses and the 1953 Elegy for viola and strings; it can

also be heard, but without Ulysses or theElegy, on a Decca

Eloquence CD with quintets by Shostakovich and Prokofiev (to

be reviewed).

Footnotes

-

Tempo No 11 (June 1945), p 5

-

The Scotsman critic (John Amis) commented the

next day on ‘the discriminating nature of their programmes’

contrasting with ‘the smallness of their audiences’, the performance

of Ulysses being ‘in the best traditions’…’Although

it is too long, this composition contains some outstandingly

fine passages’. The Morley College choir was, on this occasion,

accompanied by the Kalmar Orchestra.

-

‘A note on Ulysses’ (Music Survey, iii (1951)

p 263

-

Music Review, xii (February 1951) p 105

-

Music Survey iv/2 (February 1952)

-

Appendix to J Rufer: Composition with Twelve Notes related

only to one another ) tr Searle, p 198

-

Music Magazine (radio programme, 31 March 1957)

-

www.n-ism.org/Papers/graham_Seiber4.pdf

-

Aldeburgh Festival Programme Book (June 1959). However,

his assertion that ‘the first movement contains only series

beginning or ending with E’ is incorrect, eg the string chords

in bars 23-28 use rows from C to D (inversion) and G to A

(retrograde).

-

‘F.H.’ (probably Frank Howes) thought Seiber’s Fantasia Concertante

at the ISCM, unlike the usual fare, ‘indicated a musical mind

at work behind the abracadabra.’ (The Musical Times

(June 1949, p 203)). For Seiber’s view, cf his Composing

with Twelve Notes (Music Survey iv/3 (June 1952)

p 472.

-

I think he meant the first five notes in German or Italian

nomenclature: E – r(e diesis)- (G)i(s)- C – H(=B).

-

Radio Times (4 February 1961)

-

‘He had an encyclopaedic knowledge of music , this of all

times and climes’ (Bad Boy of Music).

Music examples reproduced by kind permission of Schott Music Ltd

|

|