These famously pyrotechnic concertos, some

of proto-Paganinian complexity, show a more public virtuosity

than the interior spirituality of, say, Biber's Mystery Sonatas.

Locatelli's own Sonatas - he wrote a number - certainly lack

the Bohemian composer's sense of profound engagement but then

Locatelli was writing from a different compositional axis; a

broadly Corellian-Vivaldian one that took an admixture of Handel

and larded it with moments of extreme, if (in our terms) rather

static melodrama. And his Concertos are certainly chin-juttingly

tough to play and have provided fiddle players with quite sufficient

difficulties over the years. The fearsome few tend to dig out

the solo sonatas - Ricci, Staryk, Kremer amongst them - whilst

such as the pioneering Lautenbacher have given us complete sets

of the concertos.

Adopting elements of the church sonata he

added finger busting double stops and exceptionally difficult

writing in the soprano register, playing that tests agility,

digital accuracy and intonation to the maximum. All the concertos

contain caprice-cadenzas, moments when the soloist lets loose

with a battery of florid cadential dramas – not for nothing

was Locatelli known colloquially as The Earthquake. Slow

movements are lyrically etched, such as the first in D major.

Opening movements, as often as not Andantes, can move, as in

the case of the C minor [No.2] with noblest of treads whereas

Vivace finales can tend toward the vocalised and possess real

lyric generosity, though there are dangers aplenty.

Such things may seem schematic but Locatelli

cannily varies texture and tone; the stratospheric finger board

work in the concertante parts of the E major [No.4] are contrasted

with the greater concentration on the lower strings in the powerhouse

cadenza. And lest one think him a flâneur, melodically speaking,

he spins a haunting Largo in the same Concerto. He also manages

to spice up a compositional trick whereby the spaced orchestral

chordal introductions to the slow movement become, over time

and as the concertos develop, quicker. The move generally is

toward a greater concision of utterance and a greater compression

of musical ideas, even if in the case of the Largo of No.11

it has become generic through overuse, and even though the last

of the twelve, the G major Facilis aditus, difficilis exitus

(an appropriate Latin tag), has an inordinately long

but clever finale – the longest single movement of any of the

concertos.

The principal competition to this newly released

set of the cycle made by Mela Tenenbaum between 1994-98 is the

set of recordings made in 1990 by Rudolfo Bonucci and the Orchestra

da Camera di Santa Cecilia on Arts 4772-2, a four CD set in

a handy slipcase. Differences are plentiful. In the main Bonucci

is more leisurely in terms of tempi and the harpsichord is much

more audible in the recorded balance. Tenenbaum was recorded

with three different orchestras though all were directed by

Richard Kapp and one senses their greater incision throughout.

That said I can’t hear a harpsichord in the First Concerto in

the Brilliant performance and the cello continuo line is rather

submerged. Against that I welcomed the Brilliant team’s greater

attention to expressive diminuendi and lighter tone. The recording

venues obviously changed for the new team and that is reflected

in the rather less immediate sound generally in comparison with

the sturdy Arts sound. Interpretatively the Bonucci team tends

to more old-fashioned notions of expression whilst the Brilliant

tend to accent with great rhythmic impetus. That this is not

a question of tempo can be evidenced by the performances of

baroque violin music of Andrew Manze who’s never afraid to indulge

a slow tempo in the interests if emotive depth. I admired rather

more the sense of paragraphal sculpting Tenenbaum finds in the

Largo of the Seventh Concerto and also her rather greater tensile

strength. Robust though they are the Arts team has to cede to

the Brilliant in the concluding Allegro of the Ninth in terms

of imaginative colour.

In the virtuosic demands of the last three

of the set we find Tenenbaum fearlessly tossing off passagework

– though Bonucci is no slouch and his harmonics are splendid.

The Labyrinth Concerto, the Twelfth, sounds very much

more innovatory and revolutionary in this new recording than

it does with Bonucci, who tends to present a more patrician

front and by implication to relate it much more to the earlier

concertos in the set, giving it a greater expressive consonance.

With Tenenbaum and Kapp you are also aware of the radicalism

that runs throughout and the colour is altogether different;

in fact they could be playing different editions their performances

are so different in almost every respect.

My choice would be for the Brilliant team

over the Arts though I should say that though Bonucci’s intonation

is occasionally compromised somewhat and there are instances

of strained passagework he remains elegant and generally unruffled

by the exorbitant demands placed on him. Tenenbaum and Kapp

take Locatelli more by the scruff of the neck and the vitality

and innovation of the music is perhaps better revealed in their

performances, imperfect though they may sometimes be.

Jonathan Woolf

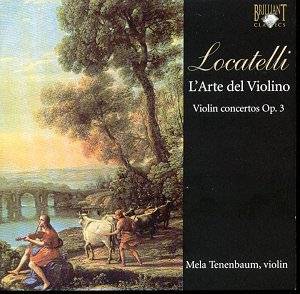

![]() Mela Tenenbaum (violin)

Mela Tenenbaum (violin)![]() BRILLIANT CLASSICS 92608

[4 CDs: 65.27 + 50.58 + 56.30 + 57.48]

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 92608

[4 CDs: 65.27 + 50.58 + 56.30 + 57.48]