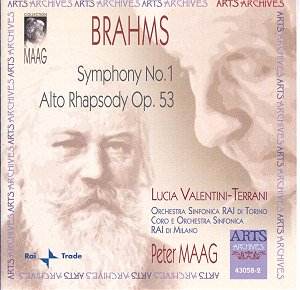

Arts Archives are clearly

dedicated to preserving the art of Peter

Maag, an under-recorded conductor after

his brilliant start on Decca. Having

succeeded in making a number of recordings

of him in his last years, notably a

Beethoven cycle but also Mozart, Mendelssohn

and Gluck, they are now making a selective

trawl of the RAI archives, which contain

a vast array of his performances over

a period of some thirty years. Since

various off-the-air bootleg issues have

given the idea that the RAI is a pretty

dicey source of historical material,

I should emphasise that these are official

releases bearing the RAI-Trade emblem.

They use the original master tapes which

are revealed, apart from a miscalculation

in the Rhapsody which I shall come to

later, to be extremely fine with excellent

stereo definition and a rich, warm sound.

Furthermore, if the name of the RAI

orchestras spells horror in some quarters,

in the seventies the Turin orchestra

in particular was at some sort of peak.

This was evident from the recent Mendelssohn

issue and the Cluytens recordings of

Honegger and Debussy on this same label;

altogether richer in timbre than the

band which Maag’s master Furtwängler

had conducted from this same rostrum

more than twenty years earlier, a recording

some readers may know. They are not

immaculate, but immaculacy was not one

of Maag’s primary concerns (or Brahms’s?)

and they respond warmly to the phrasing

and shading he calls for. No doubt the

BPO or the VPO would have been better

still, but we need not feel that Maag’s

interpretation is reaching us in an

imperfect form.

The notes suggest that

Maag’s neglect was caused by his sudden

flight to a Tibetan monastery for nearly

two years and the consequent cancellation

of a many important engagements. Maag

himself confirmed this view in an interview

- which can be found on the Internet.

I beg to suggest, however, that there

were other reasons too. As time went

on Maag’s interpretations had become

increasingly unpredictable and personalized.

I remember attending a performance of

Mendelssohn’s "Scottish" Symphony

in Milan in about 1978 or 1979 where

the music came to a complete standstill

on several occasions, very different

from his famous Decca recording of the

same work. At the time I found it perplexing

though I admired the wholehearted response

he got from the orchestra.

And so it is with the

First Symphony here. The first movement

begins with a well characterized introduction

and the Allegro itself gets under way

with much tragic impetus. Then the tempo

slackens ... and slackens ... and slackens

until it practically comes to a standstill,

then picks up, of course, then during

the development comes to another halt,

and so on. Similar things happen in

the finale, and at certain moments in

the Andante sostenuto, already expounded

at a luxuriantly expansive pace, the

music drifts into almost motionless

contemplation. Maag goes further in

this direction, in fact, than his master

Furtwängler who in Turin made creative

use of the orchestra’s thin sonority

to produce a lean, classical reading

which might surprise his admirers as

well as his detractors. I would say

that only Celibidache, in the post-Furtwängler

era, approached Brahms with comparable

romantic license.

For the truth is that,

for much of Maag’s career, he was increasingly

adopting an interpretative stance that

was out of fashion. Furtwängler

is venerated today but in the fifties

and sixties it was still Toscanini who

held sway. Most of Furtwängler’s

records were out of the catalogue (only

his Tristan kept a permanent place)

and were often rudely dismissed by critics

when an attempt was made to revive them.

The craze for searching out Furtwängler’s

live performances began in the seventies

and reached its peak in the eighties,

when saturation - virtually everything

that survived had been issued - led

to a reassessment of other romantically-inclined

conductors. The Berlin Philharmonic’s

decision to appoint Karajan rather than

Celibidache as Furtwängler’s successor

was practically an official burial of

the romantic approach to music-making.

So Maag’s big crime

was that he was a romantic interpreter

in a world that didn’t want romantic

interpretations. His special brand of

romanticism seems to have stemmed from

his love of opera. Though undoubtedly

dedicated to the symphonic repertoire

I have the idea that his greatest love

was opera, but even here he was a throwback

to the age of the conductor and this

was the age of the producer. In what

should have been a glorious milestone

in his career, his Paris "Ring",

he fell foul of a producer (I forget

who it was) who demanded faster tempi

and, when he didn’t get them, imposed

maximum timings as an ultimatum, forcing

Maag’s withdrawal. As the press pointed

out, Maag’s timings were not particularly

long and shorter than Furtwängler’s.

However, in later life Maag organized

an annual opera class in Treviso, near

Venice, where singers chosen through

an audition-competition were patiently

prepared for a production of an opera.

Quite a number of subsequently famous

singers went through this class.

The relevance of this

is that Maag’s approach to musical architecture

was more an operatic one, where each

episode is given maximum characterization

and structure is created by the placing

of climaxes rather than by aligning

everything to a uniform rhythmic trajectory.

This differentiates him from the superficially

similar Celibidache who appears to have

had no interest in opera. And it differentiates

him from practically every other conductor

contemporary with him. Toscanini had

decreed that things should be done otherwise

and oddly enough even a conductor like

Bruno Walter, who could be thoroughly

romantic in other contexts, took a fairly

classical view of Brahms.

Does this mean that

Maag was wrong? Not necessarily. The

conductors whose roots go back to Brahms’s

own world and who left us recordings

are fairly evenly divided between romantics

(Mengelberg) and classics (Weingartner).

Maag certainly reveals a side of Brahms

often passed over, bringing him closer

to the Lisztian-Wagnerian camp than

to his usual severe self. At the very

least his view deserves a hearing.

In Milan three years

later the engineers unfortunately had

the singer’s mikes turned up too high

for her first entry, where she dwarfs

the orchestra. I get the impression

they very gently lower them, a bit at

a time, so as not to create a jolt,

with the result that the singer wanders

from left to right of the soundstage

until the balance settles into the right

one and the recording then becomes a

fine one. Fortunately Lucia Valentini-Terrani’s

voice is a magnificent instrument which

can withstand such close scrutiny, rich,

even and luscious in a very Italianate

way, but always in sympathy with the

music. She loved the piece very much

and made no studio recording of it.

Maag’s conducting is again heartfelt,

softer-edged than Klemperer’s would-be

Mahlerian rendering with Ludwig and

sufficiently forward-moving to avoid

the longueurs of the funereal Ferrier/Krauss

reading. With the proviso over the recording,

this seems to me as rewarding a performance

as any in the catalogue.

Might Maag yet become

a cult figure? If he doesn’t it won’t

be for lack of trying on the part of

Arts Archives and I for one will certainly

be interested to see what they come

up with next.

Christopher Howell