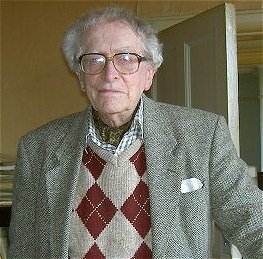

ROY DOUGLAS

by John Walton

Roy Douglas was born in Royal Tunbridge

Wells, Kent on 12 December 1907. Roy

started to play the piano when he was

five, and at ten he was composing little

piano pieces. His mother squeezed a

shilling a week out of her meagre housekeeping

money to pay for lessons "so that

I could learn to play from the music",

but because of recurrent heart trouble

he had very little formal education

as a child, and he never had any lessons

in composition, orchestration or conducting.

From the age of eight,

when well enough, he "spent many

hours playing the piano, reading at

sight everything I could find from Beethoven

to ragtime". The family moved to

Folkestone, Kent in 1915, and in his

teens he played regularly in local concerts.

When he was 20 he joined the Folkestone

Municipal Orchestra as mustel organist,

deputy pianist, celesta player, extra

percussionist, librarian and assistant

programme-builder – all for £6 a week

for 14 performances and two rehearsals.

When Folkestone Council

cut orchestra salaries Roy resigned

and made a "decidedly risky"

move to the world of music in London,

where he lived in Highgate with his

parents and sister, Doris. But the move

paid off, for he was soon talent-spotted

by the London Symphony Orchestra and

from 1933 he was a full member, as pianist,

organist, celesta player, fourth percussionist

and librarian.

Among the distinguished

conductors under whom he played were

Bruno Walter, Hamilton Harty, Adrian

Boult, John Barbirolli, Henry Wood and

Malcolm Sargent. In addition, he played

many ballet seasons at the Alhambra,

Coliseum and Drury Lane theatres. He

recalls playing the piano part in Petrushka

eighty times, and "in the Prince

Igor dances I played triangle and

tambourine, both parts together, one

with each hand."

During the 1930s he

played the piano in many West End shows

including revivals of The Desert

Song and The Vagabond King as

well as performing light music in such

well-known restaurants as the Savoy

and Frascati’s, and in many popular

cinemas.

"Disgusted and

horrified by the many bad orchestrations

of Chopin’s music for the ballet Les

Sylphides," he writes, "I

eventually created my own orchestration

in 1936." For this work, he was

originally offered an outright fee of

£10. However, Roy’s version published

by Boosey and Hawkes, was quickly taken

up and continues to be used by ballet

companies all over the world. It has

also been recorded many times, so that

it still produces a useful income of

several thousand pounds a year.

As an orchestrator

Roy was indefatigable during and after

the Second World War and worked with

many composers including William Walton,

John Ireland, Alan Rawsthorne, Walter

Goehr, Arthur Benjamin and Anthony Collins.

He prepared a full orchestral arrangement

of Liszt’s Funerailles, and orchestrated

all Richard Addinsell’s music for eight

BBC programmes and 24 films, "including

the notorious Warsaw Concerto"

(Chappell & Co. Inc. New York: 1942).

He also arranged orchestral accompaniments

for such well-known singers as Peter

Dawson, Paul Robeson, Elisabeth Schumann

and Richard Tauber for HMV recordings.

"From 1944 until

the death of Ralph Vaughan Williams

in 1958," he writes, "I had

the unforgettable experience of being

his friend and musical assistant, helping

him to prepare works for performance

and publication, including his last

four symphonies and the opera Pilgrim’s

Progress. As Roy makes clear in

his book Working with Vaughan Williams

(British Library Publishing: 1988),

the composer’s manuscripts were very

difficult to read. A large part of his

job was to provide accurate and legible

copies, and to correct the numerous

mistakes in the original scores. He

also had to deal with the many changes

made in rehearsal, and to correct proofs.

Vaughan Williams described

this process as "washing the face"

of his music, while Roy saw himself

as a "musical midhusband"

to the composer’s new-born works. For

30 years, from 1942 to 1972, he performed

a similar service for William Walton,

whose scores were not quite so difficult

to read. But he, too, would frequently

change his mind, often at the very last

minute.

Over the years Roy

has composed many original works including

an oboe quartet (1932); two quartets

for flute, violin, viola and harp (1934/1938);

a trio for flute, violin and viola (1935);

Six Dance Caricatures for wind

quintet (1939), Two Scottish Tunes

for strings (1939); Elegy for

strings (1945); Cantilena for

strings (1957); Festivities and

A Nowell Sequence for strings

(1991). He has written music for 32

radio programmes, five feature and six

documentary films. "In my 70th

year I started writing music for brass

band, and when I was 73 I wrote my first

piece for military band commissioned

by the WRAC." Since then he has

mainly composed pieces for local players

and is an energetic President of Royal

Tunbridge Wells Choral Society

(www.rtwcs.org.uk).

In 1943 Roy was one

of the founder members of the Society

for the Promotion of New Music and an

early committee member of the Composers’

Guild of Great Britain, formed in 1944,

and was their Treasurer for five years.

In 1939 Roy moved back

to Royal Tunbridge Wells, and after

the Second World War he joined the local

Drama Club. "For 22 years, I found

acting an excellent way of forgetting

musical problems." He played many

roles, including Oberon, Shylock, Touchstone,

Ben Gunn and Dr Chasuble, and produced

three plays on the Pantiles (the colonnaded

walkway in Royal Tunbridge Wells). For

eight years he was Chairman of the Tunbridge

Wells Drama Club.

Motor-cycling was another

recreation which gave Roy great pleasure.

When he was 51 he bought a Triumph 200cc

Tiger Cub, which took

him all over England. This "lively

little bike" was replaced by a

Triumph 350cc on which he covered more

than 55,000 miles – until he was 80,

when his doctor put a stop to this "possibly

eccentric" activity. "But,"

Roy adds, "I still feel sadly deprived

of my beloved motor-bike."

John Walton ©

2005