I’ve just been complaining

about the disappointing BBC studio sound in the Curzon disc in this

series (but don’t miss it for the live Liszt – BBCL 4078-2) so I’ll

start by saying that this is pretty good. If without the full range

of modern recordings it still falls attractively on the ear. In any

case, posterity seems destined to have to appreciate Richter through

live recordings in subfusc sound, and this is marvellous compared with

most of them. Oddly, though the audience can be heard, there is no applause,

and the audience rustlings continue after the end of each piece. Did

audiences in those days still think you shouldn’t applaud in a church?

In his last years Richter gave frequent performances

of Mozart concertos notable for their unflappable deliberation. This

manner of playing Mozart is revealed to have deep roots, for back in

1966 the first two movements of the K. 283 sonata were already dealt

out with an Olympian calm. Given the beauty of the sound and the musicality

of the phrasing this has its own rewards, though I felt that a little

more expressive inflection would not have been amiss in the Andante

(Richter gives us a full clutch of repeats). The Finale, on the other

hand, seems a little aggressive. There are pianists who relish Mozart’s

interplay of themes as though each one is a character on the operatic

stage. Richter concentrates wholly on the sheer musical value of the

notes. Or so it seems to me. After I had prepared this comment in my

head I read Chris de Souza’s notes which state such an opposite view

that it seems fair to quote it: "As Richter shapes the phrases

and shades the contrasts, it is easy to imagine an operatic scene, the

apparently seamless flow of the music holding together fleeting changes

of mood and manner".

In the Tchaikovsky pieces, often dismissed as very

minor chippings from his workshop, Richter again plays no tricks. The

music is presented as it appears on the page, as beautifully as possible,

and this has to be enough. In a way it is. But, just as Richter seems

to turn a deaf ear to one essential aspect of Mozart, the operatic side

of his personality, so he seems, in his rigorously musical presentation,

to ignore both the pictorial and the balletic sides of Tchaikovsky’s

make-up. The Barcarolle has a deliberation which almost wilfully avoids

any sense of the lapping of the water, and the contrapuntal lines are

to be appreciated for their intellectual value rather than as two dancers

weaving around each other. In its severe way it is very beautiful. I’ve

heard plenty of performances of Troika where the sleigh bounds joyfully

over the snow; Richter makes us hear the first part as an abstract piece

of melodic/harmonic writing. Then the middle section flashes away and

the theme returns at a more "normal" tempo. According to de

Souza the first section "perhaps represents the conveyance standing

still as the passengers climb in". Well, in this performance it

does sound like that, but was that Tchaikovsky’s intention?

These two pieces are the most popular, most characterful,

of "The Seasons". Where the composer is in unusually bland

form, in May and January, Richter extracts more music than one would

have thought possible.

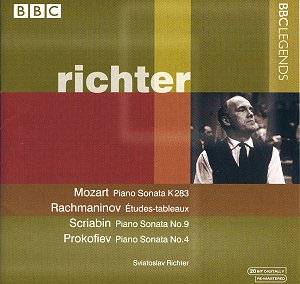

Still, I think the success of the Rachmaninov, Scriabin

and Prokofiev pieces may be to do with the fact that their inspiration

derived from the piano itself rather than from external visions which

were then realised on the piano. The Rachmaninov are a splendid display.

At 7’28" the Scriabin is conspicuously shorter than the 1965 Carnegie

Hall performance (9’18") by Horowitz – hardly a pianist noted for

his slow tempi! Both have their validity. With Horowitz every detail

is sharply etched while Richter gives us a more impressionistic rendering,

letting notes and colours run into each other in a hedonistic riot.

The Prokofiev is expounded in an exemplary manner, every contrapuntal

line rigorously clear (no mean feat as the long melodic lines entwine

around each other in the slow movement). Some cliff-hanging performances

of the finale may convey more excitement.

Richter was a very great pianist, and a very great

enigma too. He could respond to the inspiration of the moment with playing

that was white-hot, but he could also be didactic. On 19th

June 1966 he was the latter, but hear him anyway, for he always makes

you think about the music he plays.

Christopher Howell