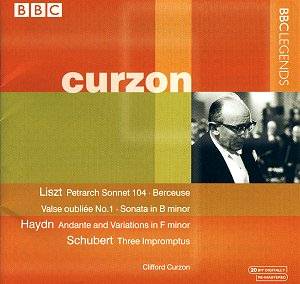

I listened to this inside out (Haydn, Schubert, Liszt)

since it seemed the logical order, but I had to admit the disc’s planners

had a point. Though the live recording from Edinburgh is not faultless

(whether it is the instrument, the acoustic or the recording equipment,

it comes out a little middle-heavy; the fault is unlikely to have been

Curzon’s) you quickly get used to it, and the pianist’s wonderfully

luminous softer touches are well caught. The performances are absolutely

terrific. Unlike Horowitz’s grand passion and Lipatti’s poetry, Curzon

takes a riskier line with the Petrarch Sonnet, with surging emotion

and withdrawn musing placed side by side rather than aiming for a straight-through

approach; and his fingers seem to probe deeply into the keyboard in

search of Liszt’s harmonic subtleties. Curzon’s own nervous tension

is palpable, but, while in the recording studios this could cause him

to freeze, in front of a public it transforms itself into an almost

desperate urge to communicate. After a magically lucid Berceuse and

an often impish Valse Oubliée, the Sonata can only be called

phenomenal. Much of it is inspired cliff-hanging, as though Liszt’s

own more demonic aspects had taken such possession of Curzon as to lead

him again and again to the brink beyond which all hell would have been

let loose. You sense that the pianist is taking unforeseen and unsuspected

paths on the spur of the moment. Rarely has a performance revealed more

fully Liszt’s creative schizophrenia, for the softer, more lyrical moments

are frequently heart-rending.

Performing did not come easily to Curzon; nerves and

insecurity often made concerts an ordeal for him. Those born without

the artistic urge might well ask why he insisted on going through with

it when he could have sat quietly at home reading the newspaper. Few

performances show better than this one why an artist just has

to go on and play.

Things are calmer in the BBC Studios. Unfortunately

the close recording robs us of some of the Curzon magic. Not so much

in the Haydn, which finds a wealth of colour and expression in a piece

which, though reputed to be among its composer’s best, can sound anything

but that in the average college student’s hands. The Schubert seems

to find Curzon in a strangely aggressive mood with a composer he very

much loved – though more distance and bloom to the sound might have

created a different impression. As it is, Curzon’s Schubert is best

appreciated elsewhere.

Still, the Liszt’s the thing. It enters the select

Panthéon of the very greatest recorded performances of this composer

and no lover of great pianism should miss it.

Christopher Howell