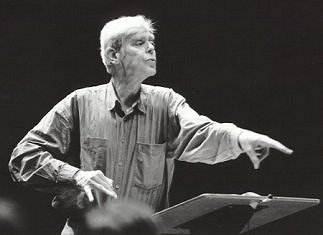

Schubert, Beethoven, Orchestra of the 18th Century, Franz Bruggen, 27th May 2003, Barbican Centre (AR).

On forming the Orchestra of the 18th Century, Frans Bruggen explained:

"I founded my own orchestra, the Orchestra of the 18th Century, because orchestras of this type didn’t exist [in 1981]. I wanted a performing orchestra to tour with…We all know each other in our world so our orchestra consists of the best specialists drawn from 19 countries. It’s a project orchestra. It exists only for two or three periods each year but always with the same people. They fly into Amsterdam or London, or any central place and after a week’s rehearsal we go on tour."

Throughout the evenings immaculate playing this ‘project orchestra’ produced a unique sound: refined, delicately translucent textures, but with a great depth and richness not usually associated with ‘period’ playing, where the reduced string section, for instance, can often sound etiolated and wiry, and the period brass sound merely tinny. While this was a reduced orchestra (with just three double basses) it had as much weight and body as a full-scale ‘modern’ symphony orchestra.

Bruggen seems to be one those rare conductors who can negotiate (and overcome) the Barbican Hall’s notoriously reverberant and stifled acoustics. Throughout, the conductor mastered the marriage between space and sound, with the orchestral balance being perfectly judged, with none of the congestion or blurring which seem to be the rule at this venue.

While this seemed initially yet another ‘classical pops programme’ the results were far from routine or predictable: the reading of both scores was revelatory, making these very familiar favourites feel like premieres.

Unexpectedly for this ‘classical’ conductor, the first movement of Schubert’s Eight’ Symphony was taken very slowly, with the conductor adopting tempi reminiscent of Karl Bohm’s turgid, romantic reading of the ‘Unfinished’, but in a classical period style; a contradiction in terms in music!

In the second movement, Bruggen got the tempi perfectly, making the music flow organically. Throughout his beautifully prepared reading it was the incisive and crisp playing of the timpanist, using hard sticks, that gave this deeply moving performance a cutting edge. The use of hard sticks, essential for this tragic, brooding symphony, revealed the importance of the timpani part, so often obscured by the customary modern use of soft sticks.

Bruggen’s performance of Beethoven’s Third Symphony ‘Eroica’ was a carefully thought out performance, with structure, dynamics and orchestral balance having total unity. The first movement - Allegro con brio - taken with the exposition repeat, had a lucidity and lean economy verging on the skeletal: this was Beethoven stripped bare of rhetorical excess with the structure of the music shining through. Again, the use of hard sticks gave this movement greater intensity and bite, particularly in the tight, assertive closing bars.

The Marcia funebre: Adagio assai was taken at a brisk pace but in the context of Bruggen’s ‘period’ performance it did not feel rushed, and the drama and tension were well sustained. With the short Scherzo, the woodwind were perfectly balanced, with all the intricate detail coming through, while the horns barked beautifully.

Bruggen launched straight into the Finale: Allegro molto making the music sing with the angular dance rhythms accentuated amidst the swirling woodwind and strings. The closing passage for sustained strings and flute was very subdued and measured which created even greater suspense and tension before the orchestra launched into the closing bars, which exploded with penetrating brass and timpani.

‘Period instrument’ orchestras can be a bit of a lottery – one can never be sure that the music will not sound merely anachronistically ‘quaint’. This doubt was quickly put to flight by Bruggen’s total mastery of his orchestral resources, and his highly intelligent reading of the works. What made his ‘period’ approach so refreshing was the incredible orchestral detail which came through in both works, revealing innovatory, even revolutionary, elements and textural beauties often submerged by today’s standardised, streamlined treatment of Schubert and Beethoven.

Alex Russell

Return to:

Return to: