S & H Festival Review

Salzburg Festival 2003: Mozart ‘Don Giovanni’ Vienna Philharmonic dir. Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Thursday August 21st 2003 (ME)

‘Who’s conducting?’

‘Harnoncourt.’

‘Aha. Long evening, then.’

This little exchange with a musician friend on the previous evening should have alerted me, but I was still unprepared for quite the kind of slowness which we experienced at this performance: four hours and ten minutes is the norm for Wagner or Strauss, but for Mozart’s ‘Dramma giocoso in due Atti?’ Oh well, what’s a bit of muttering ‘This is supposed to be a minuet, not a dirge!’ through gritted teeth, when so much else is the real thing? Whatever indignities Salzburg may have inflicted upon ‘Die Entführung,’ this ‘Don Giovanni’ does Mozart proud with a production which looks fabulous (as well as actually making sense) and some of the finest singers I have ever heard in these roles.

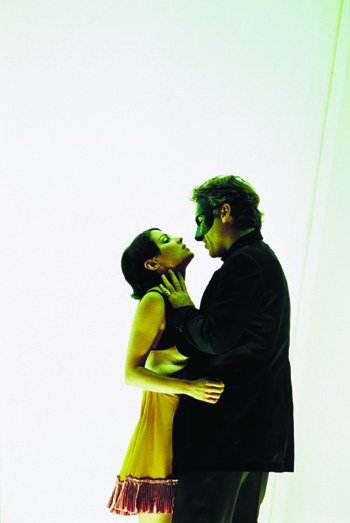

As the Vienna philharmonic give us the overture – beautifully if lugubriously – we feast our eyes upon a huge representation of five lissom lovelies, carefully chosen to represent a wide range of skin colours, reclining seductively in their gorgeously lacy hosiery – I looked in vain for the name of ‘Wolford’ amongst the sponsors. That languid, static feeling is replicated in the action, since no one seems to exert themselves very much, certainly not Thomas Hampson as the Don, who strolls through the role in his by now trademark imperial purple, just being ‘der Hampson’ with his air of hauteur and clear personal belief in his own irresistibility to the ladies. This may come as a surprise to him, but just as women over the age of about 45 become invisible to most men, so most men over that age are really a bit pathetic when they try on all that ‘ageless charm’ bit, simply coming across as old roués. The ladies come to him, is the implication – well, they might for some of the singing, but it’s fairly varied at the moment. Of course, there are very few baritones around who can caress a line like ‘Là ci darem la mano’ as seductively as he does, and his singing of the Serenade (mostly given in total darkness – extremely effective) was quite beautiful, but there’s more to the role than that: ‘Fin ch’ han dal Vino’ was lacklustre, and his exchanges with Leporello needed much more of a sense of conflict. Above all, there’s nothing risky about this Giovanni, either in his singing or his characterization.

Ildebrando d’Arcangelo’s Leporello is well known to London audiences, and he sings with suppleness and acts with as much vigour as the production allows: his ‘Catalogue’ aria was neatly rather than excitingly sung, all the excitement being in what was going on behind him - a series of stunning tableaux depicting women in various guises of vulnerability, from a society belle through a young woman shaving her legs to, shockingly, a white-clad little girl with a skipping rope. The transition here from aria to following scene was brilliantly done, with the final tableau of wedding-dressed brides becoming Zerlina’s and Masetto’s party: the costumes here, as indeed throughout, were inspired – I wanted to wear almost every dress, and how often can one say that – I would tear up most of what I normally see on stage and give it to my cleaner for dusters.

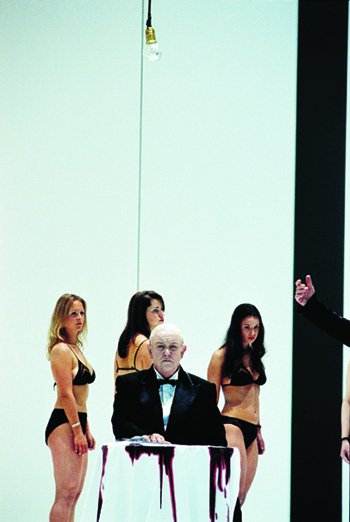

The veteran Kurt Moll’s Commendatore was effectively staged, his blood shocking against the white walls in Act 1, and at the end his sudden presence, black-tied, at Giovanni’s dinner table provided the frisson it so rarely does. His voice may not quite be what it was when I heard him as Osmin, but he still knows how to phrase a line and give it meaning. Luca Pisaroni’s Masetto was a fully rounded character, not too much of the blockhead and he sang his music with gusto. The Ottavio of Christoph Strehl is very much a work in progress: I was keen to hear him after his superb Walther von der Vogelweide at a London concert ‘Tannhäuser,’ and his is a genuinely lovely voice although rather small for this house and as yet missing some subtlety. The director sees Ottavio as a petulant youth who finds it hard to keep up with what’s required of him, which has some foundation in the music although the best Ottavios bring out something else in the part, namely the selfless nature of that true love which forms the opposite to Giovanni’s soulless adventures. Strehl may have a little way to go, but his voice is lovely and he is a very musical singer with all the right instincts: ‘Il mio Tesoro’ was eloquently delivered with only a trace of strain, and I look forward to hearing more of him.

And so to the women, who were simply the best trio I have ever heard on stage in this opera. There are plenty of great recordings, but one so rarely finds all three parts being sung with such genuinely Mozartean style. Melanie Diener is a wonderful Elvira: her voice is absolutely thrilling from top to bottom, her shimmering high notes without a trace of sourness or strain, and her mezza voce caressingly beautiful: her ‘Mì tradi’ was a tour de force of passion, vulnerability and simply wonderful tone – for me, this was the performance of the year. The Armenian-Canadian soprano Isabel Bayrakdarian was in ideal Zerlina: making her Salzburg debut, she has a creamy, mellifluous voice with bright, even projection, and her acting is unaffectedly spirited.

Anna Netrebko is one of those artists behind whom is a huge publicity machine, with DG displaying her lovely countenance all over the city, but as is too rarely the case, she actually does live up to the hype. Here is a young lady who sings like Rita Hunter and looks like Rachel Weisz – truly, and what more do you want? Both ‘Or sai’ chi l’onore’ and ‘Non Mì Dir’ were sung with gleaming tone and eloquent phrasing, and the ‘Forse un giorno’ cabaletta was beautifully articulated, each note placed with stunning accuracy. As yet, her acting is rudimentary, although she does more than many Annas to convince you of her character’s sincerity, and she looks eye-wateringly beautiful in her costumes, especially that fabulous suit with the ruched hem: she has plenty of time to grow into a more rounded stage character, however, but for now the voice has it all – buoyantly floated high notes, warm, steady middle register, exquisitely shaped phrasing: this choosy audience gave her a huge ovation after ‘Non mì dir,’ which would have been deserved for the cabaletta alone. Brava.

The production has its detractors, but unlike, say, the recent one at Covent Garden, it allows the narrative to unfold without any daft extrapolations, and most of the scenes are staged with an eye for colour and a feeling for detail: best of all, the singers are allowed to sing without having to manage any idiotic business, yet at the same time there is very little in the way of mere ‘stand and deliver.’ I could see the point of the groups of ladies in varying kinds of underwear, now delectably svelte, now haggardly aged – after all, ‘Don Giovanni’ is partly about what the vicious do to the vulnerable, and this at least was made abundantly clear in those scenes. The party was superbly done, as was the ‘graveyard’ scene, and my only real objection was to the lack of any food in evidence as the Don and his henchman awaited their guest.

Musically speaking, the slowness detracted from many of the more sparkling moments: it is, after all, supposed to be a comedy despite the dark nature of the protagonist. However, Harnoncourt gave the singers the kind of loving support which is so rare in the opera house, with the arias shaped so as to allow them to breathe and to develop their character, and there was much beautiful playing to savour, especially from the ‘cellos and Cor Anglais.

It’s easy to be swayed by the Festival atmosphere in such a place as this, a fact well known and indeed exploited by many artists who more or less confine their big appearances to such places in the certain knowledge that they will have a much easier ride – in critical terms – than in a more ruthlessly discriminating environment – witness the absurd adulation given to certain singers at the Edinburgh Festival and contrast it with their reception at, say, the Wigmore Hall – but this performance of ‘Don Giovanni’ would please the most discerning of Mozart lovers, especially in terms of the singing of the ‘Three Ladies,’ and certainly made the current ROH production look amateurish by comparison.

Melanie Eskenazi

Title: Don Giovanni

Copyright: Hansjörg Michel

1. Kurt Moll

2. Thomas Hampson, Melanie Diener

3. Anna Netrebko, Thomas Hampson

Return to:

Return to: