S & H International Festival Review

Hans Werner Henze, ‘L’Upupa und der Triumph der Sohnesliebe’ Vienna Philharmonic, dir. Markus Stenz, Salzburg, August 20th 2003 (ME)

‘The Hoopoe and the triumph of filial love’ is, according to the composer, Henze’s last opera, and its premiere at the Salzburg Festival was a major musical event. This lyrical, image-laden work is clearly a logical development for this ‘…north German contrapuntal temperament projected into the arioso South’ as he described himself, since it stems so naturally from the sensuousness of such works as the ‘Neapolitanische Lieder’ and even more so from the ‘Sechs Gesänge aus dem Arabischen’ of 1999: these songs were based partly on free verse collages and the composer’s own texts, so it is hardly surprising that for the present work he chose to write his own libretto, like Wagner utilizing the vast treasure chest of what Philip Larkin referred to as ‘the Myth-kitty’ and fulfilling the ideal which the composer described in ‘Musical Language and Artistic Invention’ as ‘…music…as an emotion arising from the combination of pictures, concepts, form, formulae and archetypes, as an indivisible unity.’Henze wrote of the ‘Six Arabian Songs’ that ‘…the terrain is west-eastern… Creatures from an alien world wanted to be staged, and for this purpose they needed the moulding hand of an artist with a sympathetic approach like me’ and the same could be said of ‘L’Upupa’ with its confluence of east / west iconography and its ‘creatures’ in need of a shaping hand. The tale is ‘told by an Old Man, handed down from long ago’ and so Chaucerian an opening to the synopsis leads us into the association of the tale-teller with the composer, who refers to himself as ‘der Alte’ in his autobiography. The Old Man is a father of three sons, two of them ‘shabby jerks’ but the third possessing all the qualities of a hero, being, like Hamlet, ‘most generous, and free from all contriving:’ this third son embarks on a quest for the mysterious hoopoe which had eluded the old man’s grasp and left him with a wound and a single golden feather, and along the way he also discovers a Jewish princess and an enigmatic chest, discoveries in which he is aided by an equally enigmatic daemon. Of course, this being not only the stuff of myth and legend but of real, passionate life, he also discovers that the true seeker can never abandon his quest, so even when he has brought bird, chest and princess home, he must still go back to the mystical kingdom in order to obtain ‘den Apfel vom Baum des Lebens’ for his daemon and alter ego.

Both music and story unfold with serene inevitability, the two of course inseparable and indivisible: this is a work which breathes Strauss and Mahler as well as Berg, although I am sure that the composer would not be happy with mention of the first of these composers in this context. It is basically twelve tone music, but with a harmonic style of great individuality, and although it could be said to lack ‘set pieces’ of the conventional operatic form, it allows the singers to present the crises of their characters’ lives in an organic and fluid way: this is not Handelian opera, where an individual reflects on a crucial moment and then leaves the stage, but it persuades us that even though set in a mythical context, these are real people with immediate dilemmas to overcome.

The part of Al Kasim, the ‘good’ son, was written for Matthias Goerne, and it’s easy to understand how his very beautiful, burnished tones and his unaffected yet intense stage presence would have inspired Henze to compose for him. It is never easy to present a character who is without stain, ‘the devil’s party’ always being the more engaging, and Goerne has not as yet had a vast amount of experience in ‘making’ a character onstage (as opposed to his unique ability to be at one with the protagonist of a Lied) so his interpretation was very much along the lines of his familiar blend of nobility and clumsiness as seen in his Wozzeck and Papageno, elements of both being contained in Kasim’s nature. Unsurprisingly, he was at his best in moments of tenderness and impetuosity such as the meeting with the princess – ‘Ich nehme deine schwanenweissen hände in die meinen…’ and his impassioned delivery of both words and music in such phrases as ‘O Durchlaucht! Ein dunkler Schatten liegt über unserem hause’ provided ample justification for the composer’s trust in him. Perhaps in the context of a later production he will be more able to demonstrate a clearer sense of his character’s journey from eagerness to maturity.

Kasim’s relationship with his daemon is the most important one of the opera: it is the daemon who, as Henze notes, is ‘…actually an angel and therefore belongs somehow to the concept of fraternal love’ and is the genuine embodiment of the title’s ‘triumph’ of love, both in the sense that Kasim’s maturity is shown in his desire to postpone marital bliss until he has brought him back the apple from the Tree of Life, and in his own selfless assumption of suffering. The daemon is even more of a mixture of elements of other characters than Kasim, and weighted with even more symbolic implications: dramatically as well as musically, he is, as John Mark Ainsley who created the role says, ‘a combination of Papageno, Mime and Loge’ but there are also elements of a Christ-like, afflicted figure ‘taking on the sins of the world’ as well as obvious kinship with the person of the creative artist. These associations are subtle rather than signposted, although it would be hard to miss the link with the Matthew Passion when the afflicted daemon sings ‘Und abermals krähete der Hahn.’

Whatever he symbolizes, the daemon has the most vivid, exciting and varied music, and he is sung and acted with wonderful immediacy and commitment by Ainsley, who brings to bear on his assumption of the role a vast range of operatic experience despite his relative youth. In his Journals, the composer remarks that ‘…the daemon is a civilized, elegant, young tenor. I have to find a vocal style in which John Mark Ainsley and the figure of the daemon… can come to terms’ and some time later, having discovered that such daemons are really angels, Henze rejoiced in the fact that he could now write ‘a beautiful role for a high ‘lyric’ tenor.’ A beautiful role it is, in fact I would say that one would need to go back to Strauss’ writing for the soprano voice, to find another part so finely written, and Ainsley gave it exactly the right combination of pathos and whimsy, narrating incisively (even getting some laughs from this most serious of audiences) and singing with a beauty of tone and ringing clarity that were sometimes quite breathtaking, especially in such moments as ‘...etwas, das mein Herz bewegt’ with its lovely trill on ‘Herz.’

These are two voices which sound wonderful together, and the opera’s finest moments are between them: their duet in the second act ‘Dies ist das Ende unserer reise’ / ‘…warst du doch wie ein Engel…’ was as fine as anything I have heard on the stage, either in contemporary music or before, and would alone be enough to reveal the stature of Henze’s writing for the male voice.

His feeling for the nuance of the soprano voice is perhaps less remarkable, although the character of the Princess Badi’at does not really permit so much interest as that of the fraternal heroes: the part was beautifully sung and vividly acted by Laura Aikin, whose sweetness of tone is fascinatingly underpinned by just enough steel in the timbre to render her performance really exciting despite the mainly conventional nature of such a role. There are obvious links to Pamina in that she is an imprisoned princess who is rescued by her beloved and a helpful Papageno-like figure: when she is caught in mid-escape she even sings ‘Herr, ich bin zwar Verbrecherin’ – she is of course a far less dominant figure than Mozart’s heroine. The superb contralto Hanna Schwarz made a treasurable cameo appearance as one of the ancient rulers in whose gardens are sequestered treasures which they cannot keep (shades of ‘Entführung’ here, not for the first time), and Malik’s narrative was another of the work’s high points.

The other male roles were cast from equal strength, Alfred Muff’s Old Man being an especially characterful and finely sung performance, Günter Missenhardt’s Dijab rather bluff but firm of tone, and the two feckless brothers played with striking assurance by Axel Köhler and Anton Scharib: Kohler’s counter-tenor is particularly beautiful and made me wonder why we have not heard much of him in London.

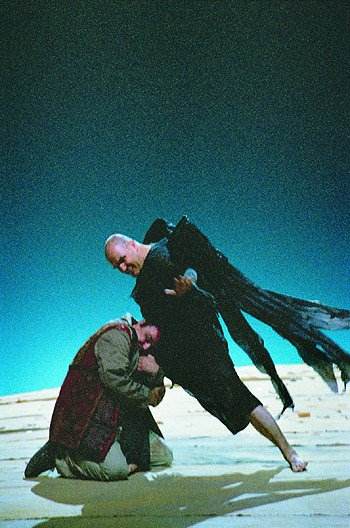

The production was a conventionally pretty one, Jürgen Rose providing plenty of delightfully colourful stage pictures and witty effects contrasted with more harrowing, starkly set scenes such as the one where the daemon, who has been almost destroyed by his endeavours on Kasim’s behalf, has his injuries bandaged by the lovers. The tenderness between the two main characters was wonderfully shown in their scenes, and perhaps the most striking parts were those where the Old Man and the Princess watch Kasim’s departing figure as twilight falls, and where Kasim flies off on the daemon’s back, with a pair of vast black wings beating and fluttering above them.

That fluttering of wings ‘like the beating fan of an Oriental courtesan’ is the sound which begins the opera, and it occurs throughout like a motif. The Vienna Philharmonic played with expected sheen of tone, gently guided through the music by the superb conducting of Markus Stenz, another name which seems to be less frequently seen than in should be in London. It was this orchestra which played for the premiere of ‘The Bassarids’ – Henze remarked once that he had had ‘their sound in my ears as I was composing,’ and that characteristic sound was heard to best advantage in this intimate theatre.

Are there weaknesses in this work? Certainly, some minor ones do suggest themselves: when Henze was in the early stages of composition he remarked that ‘…the whole thing need not last much more than an hour and a half, and perhaps then it can be played without an intermission’ and one can only assume that it later developed in such a way that greater length became necessary, but there are still some longeurs, principally in the second half, and some moments when it feels as though a narrative has gone on for too long. The music is beautiful, precise in detail and inventive, as always with Henze, but some may feel that it lacks great ‘arias,’ for want of a better word. Nevertheless, this is an important work by – arguably – the greatest living composer, directed with style and performed with commitment by a cast which it would be difficult to equal anywhere. The production will go from here to Madrid and Berlin, but not, of course, to London.

Melanie Eskenazi

Title: L'Upupa und der Triumph der Sohnesliebe

Copyright: Clärchen & Matthias Baus

1. John Mark Ainsley

2. Matthias Goerne, Laura Aikin

3. Matthias Goerne, John Mark Ainsley

Return to:

Return to: