S & H Opera Review

MAW: Sophie’s Choice, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 7th December, 2002 (MB)

Narrator, Dale Deusing

Stingo, Gordon Gietz

Sophie, Angelika Kirchschlager

Nathan, Rodney Gilfry

Librarian, Adrian Clarke

Yetta Zimmerman, Frances McCafferty

Zbigniew Bieganski, Stafford Dean

Wanda, Stephanie Friede

Eva, Abigail Browne

Jan, Billy Clerkin

Rudolph Franz Höss, Jorma Silvasti

ROH Chorus & Orchestra, Sir Simon Rattle

Nicholas Maw’s new opera, epic in its breadth and scope, is a notable achievement. Notable for its singing and notable for its staging; it looks impressive and it is. Yet, there are problems with the first half of the opera in that dramatic pulse is somewhat eradicated; at times, the action does draw to a halt (one suspects that Maw will revisit his score and tighten this up; already there has been some re-orchestration at key moments). But this really only affects the first two acts of the opera where after the action and psychology of the opera take a firm grip on the listener. This is not necessarily Maw’s fault since Alan J Pakula’s film version of Styron’s novel nurtures a similar lack of pace, energised as it is by the performances. It is Trevor Nunn’s achievement that he encourages his three principals to hold that lack of tension together with acting that matches the beauty of their voices.

Any opera which requires seventeen scene changes (excluding the Act IV interlude, largely staged in black with the Narrator spot-lit) demands an imaginative approach, and by and large the designer Rob Howell has achieved this. Less is made of the stage than one might imagine with most of the action taking place at the front in a series of interconnected moveable mini stages, representing the Brooklyn boarding house of Yetta Zimmerman and the rooms of Stingo and Sophie and Nathan. Only Scene 2 of Act II presents a logistical problem in that we have literally to be in two places simultaneously. Howell does this by having Stingo’s room raised above the stage on the top of Bieganski’s study which ominously, and appropriately, rises from the bowels of the stage. Appropriately, because this is the scene in which Sophie’s father’s exposition of the ‘Polish Question’ and the extermination of the Polish Jews is first revealed. The contrast between the two – Stingo’s brightly coloured room, partly hedonistic in its opulence, and Bieganski’s sombre book-filled study, with its long heavy table adding to its inhospitable imagery - serves almost as an intellectual treatise on the creativity which is central to this scene: Bieganski’s parenthesis on what is a Pole’s critique of the Nazi question and Stingo’s workman-like efforts on his Great American Novel.

SOPHIE'S CHOICE

Royal Opera House, London 12/02

Music and Libretto: Nicholas Maw

based on the novel Sophie's Choice by William Styron

Conductor: Simon Rattle

Director: Trevor Nunn

Designs: Rob Howell

Lighting: Mark HendersonPHOTO CREDIT: Catherine Ashmore

Act III shifts attention to Warsaw and Auschwitz. Simplicity dictates the design of both – whether it is in the barrenness of the Warsaw apartment, in part overlaid with a dispirited unctuousness, or the clinicism of Auschwitz, with its off-white rooms contrasted against the backdrop of a smoking furnace chimney. Scene 2 takes us on the journey to Auschwitz itself. Three railway carriages – more like cages than the rolling stock we are used to seeing in cinematic images of the death trains – move gradually forward from the back of the stage; it is an image which has genuine pathos.

Maw’s own libretto for the opera removes Styron’s more potent and acerbic language to the point of exterminating it. Whatever the reason for doing this (surely, modern day opera audiences can easily assimilate the odd ‘fuck’ throughout an evening) its effect diminishes the impact, the rawness, which these three lead characters are capable of throwing, like poisoned javelins, at each other. Language, as much as the fraught psychology behind the development of this tripartite relationship, is central to this opera’s ability to sustain momentum and at times Maw’s libretto is happy to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’ at the expense of revealing the real horror: which is that language, whether in its written or spoken form, is as destructive as any physical or mental act of cruelty. Nathan’s cruelty is as much verbal as it is psychological, and Sophie’s own ‘choice’ is precipitated by her statement that she is not a Jew but a Christian.

ANGELIKA KIRCHSCHLAGER as Sophie

SOPHIE'S CHOICE

Royal Opera House, London 12/02

Music and Libretto: Nicholas Maw

based on the novel Sophie's Choice by William Styron

Conductor: Simon Rattle

Director: Trevor Nunn

Designs: Rob Howell

Lighting: Mark HendersonPHOTO CREDIT: Catherine Ashmore

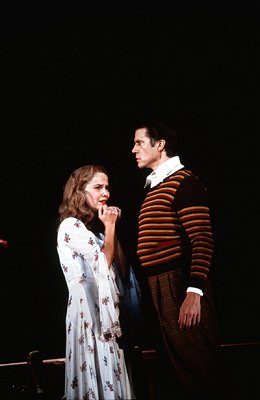

Angelika Kirchschlager, making her Royal Opera House debut, is simply extraordinary in the role of Sophie. The clarity of her (accentless) singing is remarkable, perhaps better focused in the lower registers of the voice than in the upper, but nevertheless perfectly audible and utterly transparent. What sets her apart, however, is her astonishing ability as a singer-actress – this is a role in which she brings moments of pathos, humanity, guile, innocence and helplessness through use of both the voice and her expressivity. Her exchanges with Wanda (startlingly sung by Stephanie Friede) mark her out as an actress of rare understanding: her line, ‘No – I’ve already told you I cannot help you’ is delivered with a desperation as fleeting as it is long-lasting, sung with rectitude as it is with a hopelessness that she knows she must make the right decision. When she delivers the line ‘I dare not risk it. I have to think of the children’ there is a distressed irony to her tone; later she will have to think of one child.

Her scenes with both Nathan and Stingo bring out a tremendous vulnerability in her. Whether immersed in the laughter and happiness she occasionally shares with Nathan or in the introspection and almost sublimated passion, and, ultimately, honesty, she shares with Stingo the voice takes on such colouring as to give flesh to her character. Kirchschlager simply is Sophie. One moment she can be dancing on a bed, another rolled up on it like a foetus; at another she is racked with guilt and at another as innocent as a child. When typing up her father’s speech about the Polish question she physically recoils from his change of language, ‘Change ‘total abolishment’ to ‘extermination’. Yes, that’s it: ‘Extermination of the Jewish element’. When she recounts the story to Stingo her cries of ‘Extermination! Oh God, extermination!…’ are delivered with the shrieks of a wounded bird.

Physically, her transformation from intellectual’s daughter to holocaust survivor is remarkably done. One moment her hair flows in golden tresses, in another it is shorn. A quick scene change and her flesh is pallid and ravaged by the poverty of Auschwitz; another and her flesh is like that of a painted china doll. With every change the voice also changes. This is transfigured acting and marks Kirchschlager out as one of the great singers of our time. Nowhere is she finer than in reading her letter to Stingo (the voice floating around the auditorium like a reflected image). It is a moment recollected in tranquillity.

ANGELIKA KIRCHSCHLAGER as Sophie

RODNEY GILFRY as Nathan

SOPHIE'S CHOICE

Royal Opera House, London 12/02

Music and Libretto: Nicholas Maw

based on the novel Sophie's Choice by William Styron

Conductor: Simon Rattle

Director: Trevor Nunn

Designs: Rob Howell

Lighting: Mark HendersonPHOTO CREDIT: Catherine Ashmore

The two male leads are also outstanding. Gordon Gietz’ Stingo, so handsome in looks, so limpid in expressivity, brings youthfulness to his role, in part rather a thankless one. At times there is an ambivalent child-like simplicity to his performance (more than once he just looks lost), at others (and this is when his singing rings out with a virility of tone) where he has all the attractiveness any woman could wish for in a man. When he finally gets to sleep with Sophie the passion of his singing is matched by the highly charged eroticism of his love-making. Rodney Gilfry’s Nathan is inflected with a genuine psychopathic under current. Violence and love intermingle with apparent ease, and if the voice is not often a big one he has the ability to sustain a broad legato. His finest moment comes in Act IV where he turns on Stingo. Lines like, ‘You wretched swine! You unspeakable creep!’ are delivered with venomous cruelty. When he sings, ‘And I’m coming to get you treacherous scum’ it is shockingly done. Gilfry has the knack to bring malevolence to his voice, just as he has the ability to coax both Sophie and Stingo into his own world of deception and self-belief.

Central to this production is the omnipresence of the Narrator, quite thrillingly sung by the bass-baritone Dale Deusing. The vocal part is a large one but what makes the role such a challenge is the singer’s constant presence on stage. The only non-scene change, although marked in the libretto as an ‘Interlude’, sees the Narrator spot-lit, his body writhing in pseudo-agony as he slowly pulls the letter Sophie has left Stingo after their night of passion from his coat pocket. Elsewhere he seems to act as the conscience of the opera – falling to his knees at the sight of the Auschwitz train, plunging into despair at hearing Sophie’s ‘choice’ between her son and daughter, jokingly hiding behind a chest of drawers when Sophie and Nathan are dancing in Act I. His words are spoken at the beginning and end of the opera (although this is not ‘sprech’ but lyrical, motivic singing), and throughout whether in Brooklyn or Warsaw or Auschwitz; his presence is like that of a great shadow. Deusing’s achievement – and it is a considerable one – is that his very presence never detracts from what is happening on stage. It is as if he really were a ghost to the events that inspire the tragedy of the opera.

Jorma Silvasti sings Rudolf Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz. He brings an odious arrogance to his role, and is quite chilling in his treatment of Sophie. After she has spent time pleading her case for release – ‘I am a Polish sympathiser with National Socialism’ – Höss tosses her pamphlet written by her father – and on which she claims intellectual input – to the floor before denouncing her with the words, ‘This document means nothing to me’. When she finally persuades him that her son should be released into the Lebensborn programme he relents but when we next see him it is smoking a cigarette, fingering the paper before scrunching it up and throwing it to the floor. Surprisingly, Maw has chosen a tenor (albeit a dramatic one) for the role of Höss (as he does for all the main male characters, Nathan’s high baritone much more tenorish than one might expect) and wonderfully though Silvasti sings the role (even if his English is more ‘European’ than Kirchschlager’s) it might have added dramatic weight if the role had been sung by a more darker, firmer toned baritone or bass.

Of the other singers, Frances McCafferty’s Yetta Zimmerman is a spritely sung, typically Jewish caricature of a boarding house owner. Adrian Clarke is a stand offish librarian and Stafford Dean makes much of the role of Sophie’s father, Zbigniew Bieganski (cigar smoking, arrogant and emotionally distant from his daughter).

GORDON GIETZ as Stingo

ANGELIKA KIRCHSCHLAGER as Sophie

RODNEY GILFRY as Nathan

SOPHIE'S CHOICE

Royal Opera House, London 12/02

Music and Libretto: Nicholas Maw

based on the novel Sophie's Choice by William Styron

Conductor: Simon Rattle

Director: Trevor Nunn

Designs: Rob Howell

Lighting: Mark HendersonPHOTO CREDIT: Catherine Ashmore

Nicholas Maw’s vast score is in parts a hybrid. The Auschwitz scenes don’t drain the emotions (as well they could), but the power comes at specific moments (notably when Sophie makes her choice). Much of it has a lyricism that recalls Vaughan-Williams (the Tallis Fantasia, for example, in the slow, chordal string melodies) and whilst this is not the dominant motive it is the one which begins and closes the opera (it ends palpably, in near silence, on a high, single violin’s E string). Simon Rattle’s conducting is both urgent and spellbinding, and he produces ravishing sounds from the strings, notably the burnished-sounding ‘cellos and deeply sonorous basses. Indeed, the playing is largely magnificent. There are moments of pathos and of anger in the orchestral writing, but Maw is masterly at being able to make every sung or spoken word clearly audible above the orchestra. Most of the vocal writing is for single voice, or in dialogue, with only one or two pieces for duet or quartet (excluding the choral Auschwitz scenes where the singing is mostly monosyllabic – indeed, the only word the prisoners ever sing is ‘Ah!’).

Lighting by Mark Henderson is atmospheric and David Bolger choreographs the movement between the principals and in the few group scenes well. Costumes supervised by Irene Bohan are specific to the period (correct Nazi insignia, 1940’s blue label Converse pumps for Stingo). It is a production where everything does seem to matter.

Long as the evening is, with just a single interval separating the four acts, Sophie’s Choice is a powerful exposition of its subject. Having originally dropped the idea of commissioning this opera Covent Garden should be congratulated for finally having the courage to get it off the ground. The warmth of the first night, with standing ovations for Kirchschlager and especially Maw, shows Covent Garden to have an unexpected hit on its hands.

Marc Bridle

Return to:

Return to: