The Quincena Musical Donostia (a fortnight of music at San

Sebastian in northern Spain - Donostia is its Basque name) was founded in

1961, and retains that name despite having been progressively prolonged and

enlarged over the years. This year the festival was launched with a bang

on 9 August with a whole day of 10 events around the city, and it continued

through to 3 September, based at the new Kursaal which opened last year,

with a procession of prestigious international soloists and orchestras, ballet,

and several series of early and contemporary music, settling down to three

choices each evening; something for any taste.

San

Sebastian is a fashionable seaside resort, ringed by green mountains

in the beautiful Basque country. One is by no means unaware of the political

strife in the area, though this does not really impinge upon holiday pleasures.

It has two bays with fine bathing beaches, a small port for pleasure craft,

a lively and well kept old town and a wealth of splendid buildings. If the

weather is either too hot or too wet you can dive into some interesting museums.

San

Sebastian is a fashionable seaside resort, ringed by green mountains

in the beautiful Basque country. One is by no means unaware of the political

strife in the area, though this does not really impinge upon holiday pleasures.

It has two bays with fine bathing beaches, a small port for pleasure craft,

a lively and well kept old town and a wealth of splendid buildings. If the

weather is either too hot or too wet you can dive into some interesting museums.

The understated elegance and sophistication of the Kursaal is in direct contrast to the baroque flamboyance of that extraordinary new temple to modern art, Bilbao's fabulous Guggenheim Museum, which is only an hour away by frequent, inexpensive coach service, city centre to city centre. It is, therefore, possible to nourish all your senses, aesthetic as well as physical, and to combine music with sea and sand, mountains - and gourmandising. The Basque people pride themselves, with justice, on the quality of their food and it is possible, at present exchange rates, to have a 3 course meal including wine for about £5, though you may have to take pot-luck with what you choose from the menus!

By courtesy of the Festival, we were accommodated at the Amara Plaza Hotel, situated on the tidal river, half an hour's pleasant walk from the concert halls on the seafront. Although no architectural gem, (it looks a bit like a grain silo in a busy junction with the coach station to one side) the interior is fitted out to a high specification with excellent soundproofing. The service was always courteous and efficient and the superb buffet breakfast caters for fruitarians as well as carnivores and, if you feel a bit rough, a bucks fizz (or just fizz) could give a lift to the day.

THE MONEO KURSAAL

The events we attended all took place in the new Kursaal, a visually arresting and controversial conference and arts centre built by the renowned architect, Rafael Moneo and locally dubbed the "Moneo Cubes". It comprises two blocks, which have something of the look of corrugated cardboard boxes, each slightly squashed and out of plumb, represented in the festival posters and programme as J.S.B's eyes!

The lack of true vertical and horizontal lines creates different and interesting angles of vision from every approach. There are no true verticals and one is constantly drawn back to 'read' the shapes of its perplexing exterior. One local resident wrote in during its construction to helpfully point out that it was crooked; the most costly of the city's guidebooks has its illustration 'corrected' as a proper cube!

|

|

The cladding is a double skin of translucent glass, suggesting watery waves, and the building takes on the colours of its surroundings and the weather, blue green like the sea under cloud, glowing yellow at night when, subtly illuminated, Moneo's cubes look like giant luminous rocks on the beach.

The Kursaal's three auditoria offer good sightlines and crystal clear acoustics, which can be rather harsh and unforgiving for musical performances, demanding utmost clarity and coherence from the players. Ear-splitting fortissimi retain their instrumental textures and the faintest brushes of pianissimo can fill the space with a magical sonority, but any woolly muffling is exposed mercilessly. The Moneo Cubes are uncompromising but potentially rewarding performance spaces.

HOMAGE TO DE PABLO

S&H covered a week centring on a Homage to Luis de Pablo in honour of the 70th birthday of this leading Spanish composer, and revered teacher of many in the flourishing younger generation of composers. De Pablo is entering his 8th decade, and the new Millennium, with undiminished energy and enthusiasm for music past, present and future. Having just completed his fourth opera, and still receiving and welcoming commissions, he promises himself to try to restrict his composing to mornings, devoting the afternoons for some months ahead to unlocking the compositional techniques of the masters of Flemish polyphony!

It is a serious limitation of the festival that nearly all the events take place simultaneously at 8 p.m. If the de Pablo concerts, each only about an hour of music, had been scheduled for say 5.45 or 6, many more people might have been tempted to sample the unfamiliar contemporary music? It must be said, too, that whilst the musicians are international, the festival itself is not. Information in the programme book was sparse, and only in Spanish and Basque; surprising so near to the French border!

With concert promoters having an insatiable appetite for the new, it was good that the first Pablo concert at San Sebastian was given over to a unique work in his oeuvre, and one with strong local connections to his proud Basque origins (though based in Madrid, he spends the summers composing in a Basque retreat in northern Spain).

|

|

Luis de Pablo at his Summer composing retreat |

Alexa Woolf and Luis de Pablo |

Zuresko Olerkia (1975) was given by Grupo Vocal KEA with percussion & txalaparta. It is an extraordinary hour-long creation; quiet and static, but with endlessly fascinating patterns to engage the listener. Pablo often avoids using percussion for mere power and volume, and here four players accompany the choir's sustained chords with alternating, fully notated passages on mainly tuned percussion instruments, rarely rising even to mf. They fall silent for long passages which are given over to the local Basque instrument, the txalaparta, three examples of which were placed behind the choir, to the side of the audience and at the back of the hall respectively. These are played by two unschooled, duetting musicians, who improvise together within prescribed parameters.

The txalaparta consists of several thick planks of different woods,

resting on foam supports to free their natural resonances, with which the

players become familiar only with experience. They are struck, mostly quite

gently, with two pairs of sticks, most of the time grasped around the middle

and played vertically, with smaller or larger ends to vary the timbre. The

two players work closely together and build up surprisingly complex rhythmic

patterns, which vary from performance to performance and, so Luis de Pablo

told us, from rehearsal to performance! The wordless vocal sounds mostly

float like early morning mists, not goal orientated and seemingly flowing

to nowhere in particular. After a while they separate out into spacious paths,

underpinned by the regular percussion rhythms.

The success of Zurezko Olerkia depends largely on a perfect symbiotic relationship with the concert and folk percussion instruments, which surround and frame and almost literally hold the voices in place. When the regular patterns break up the voices become forceful and almost windblown but still contained through the most virtuosic playing at this point on the traditional Basque txalaparta. The complex, embroidered and pearly woodblock rhythms, played from the sides and then from the back of the hall, weave themselves into the vocal sounds. At first they hold the voices in place, then set them free to float on their own before the professional percussionists behind the singers join in to give body to floating sounds which finally just stop, suspended in mid-air. A most thrilling and memorable event.

The uncommonly multinational Orpheus Quartet, whose members are Romanian, French & Dutch, made a very strong impression on this, my hearing of a group which has won accolades for their many recordings (I had missed them on their regular visits to London). They have been together with the original membership for fourteen years and have built up and sustained the close rapport and mutual understanding which are axiomatic for great string quartets. All are linguists with excellent English, and they work in a combination of German & French. They brought the second of two quartets (which they are also committing to CD) by the Dutch composer Tristan Keuris (1946-96), highly regarded in Holland until his untimely death. Played continuously, but with well-defined sections, I found it rather too derivative, with too many echoes of Bartók.

This was framed by two recent chamber works by the Festival's featured

composer, Luis de Pablo, his 3rd string quartet Flessuoso and

the Clarinet Quintet, in three movements, Voluta, Bagatela &

Solemne, the last holding the emotional weight of this, one of his

best chamber works. They were joined by the Spanish clarinettist José

Luis Estellés, formerly a student of Anthony Pay in London, with

whom they have worked for some time, notably in a highly competitive new

recording of the Brahms clarinet quintet, with the three string quartets,

[Turtle

499018]

![]() ).

Both of these clarinet quintets require, and with these musicians receive,

an integration and interweaving of wind and string tone which is far more

subtle than the soloistic approach in, say, the Weber quintet. Luis de Pablo's

clarinet quintet should enter the regular chamber music repertoire and would

hold its own well in concert alongside the Mozart quintet.

).

Both of these clarinet quintets require, and with these musicians receive,

an integration and interweaving of wind and string tone which is far more

subtle than the soloistic approach in, say, the Weber quintet. Luis de Pablo's

clarinet quintet should enter the regular chamber music repertoire and would

hold its own well in concert alongside the Mozart quintet.

The very accomplished Trio Arbós gave a recital of de Pablo's music, which they have recorded for col legno (release expected during the autumn). Compostela, a quarter hour piece for violin and cello duo, is a useful addition to the repertoire for that combination, but something needs to be worked out so that performers can dispense with page-turners standing next to each of the players, rather disconcerting for an audience.

The piano trio, which was much appreciated when Luis de Pablo was featured composer at Huddersfield in 1999, is establishing itself as one of de Pablo's most successful chamber works, with a substantial element of whimsical fantasy. On this occasion it sounded a little over-serious, probably on account of the dry acoustic? The Arbós have also recorded for Naxos a CD of Turina, including an early trio, which they tell me is virtually unknown.

The Plural Ensemble, who had been admired in Strasbourg last summer, gave the fourth concert in the Homage to Luis de Pablo series. They gave the piano quintet Metáforas (which had featured in the Almeida Festival concert which initially aroused my sustained interest in this composer, given in London by the Arditti Quartet with Yvar Mikhashoff many years ago) and the very successful and widely performed Libro de Imagenes for an unusual chamber ensemble of nine instruments including guitar, mandolin and harp. The progress of that, too, I have followed from its Amsterdam première to Huddersfield (London Sinfonietta) and a brilliant CD recording by the Italian new music ensemble Nuova Sincronie (see my short discography of de Pablo in Music on the Web's Composers from other countries pages). Libro de Imagenes is notable for its response to literary stimuli and for the delicacy of the instrumentation; as in the case of Zuresko Olerkia the percussion is used for colour, not power, always to telling effect. (Shortly to be released by col legno is a portrait CD of another distinguished Spanish composer, David del Puerto, including his marimba and oboe concertos.)

TWO PIANO RECITALS

Jean François Heissier is a distinguished French pianist of 50 (an age at which musicians are prone to find themselves overlooked by the media) and his contribution to the San Sebastian Ciclo de Musika del Siglo XX series of concerts consisted of four world premières by Spanish composers born in the '60s.

Two works by Etxeberria and Laskano made the stronger impressions because they explored latent characteristics of the piano specific to that instrument; most especially that of Ramon Laskano (a composer previously noted by S&H in Strasbourg, with a recommended CD, who has just been awarded an 18-month composing residency in Rome at the Villa de Medici). Laskano's El Cuarto Monologo took as its structural starting point the noise which every pianist has experienced accidentally, or deliberately perhaps when feeling frustrated, by stamping hard on the sustaining pedal and hearing the resonances which emerge beneath the lid. He developed this is conjunction and opposition with p chords, then some chords sharp and staccato, glissandi up to high trills decorating melodic figures, later heavily decorated chords played ff to maximise the resonances. This eventful work accelerates to a passage in which the melody is embroidered with acciaccaturas, with similar procedures taken down to the bass end of the pianoforte, and rolling tremolos in both hands before the piece thins gradually to a thread of tone, ending with pp single notes. This is a piece which is so striking in its musical merits that it would be worth introducing to advanced piano students to enlarge their appreciation of the intrinsic capabilities of their chosen instrument.

Carlos Etxeberria's La sombra de Y Tartalo combined heavy chords with running figurations and also succeeded in holding the interest until the interval. The visiting critic from abroad was seriously hampered in supplying background context because the only programme notes were spoken ones, delivered in such rapid Spanish as to be incomprehensible even to those who can decipher something of the language in print. (For the most part, the San Sebastian Festival provided no programme notes whatsoever, not even dates of compositions!)

The second half of Jean François Heissier's programme consisted of more conventional sounding piano music, La Fiesta by Gabriel Erkoreka, who had studied in London and had some of his music played there, and Joseba Torre, whose spoken introduction about his representation of St Johns Night was by far the longest, the piece itself sounding like an old fashioned symphonic poem with Lisztian gestures and piano scoring quasi-Rachmaninoff & Scriabin - and even a quotation from the ubiquitous Dies Irae.

All this music was delivered with complete conviction to a fairly small,

appreciative audience, suggesting thorough preparation which must have served

each composer to best possible advantage. Heissier's playing was well

adjusted to the clear, if a little dry, acoustics of the small Salas

Polivalentes, low down in the Kursaal complex. He sits still at the keyboard,

with no unnecessary movement, and his face is practically impassive yet showing

constant alertness. I have Heissier's recommendable CD of Mompou (Erato

4509-985-40-2

![]() )

and would hope to hear him again in more conventional repertoire.

This festival concert series, however, is one of those in which each artist

or group makes but a single appearance, which can seem wasteful especially

in the case of those who have travelled a long way to take part.

)

and would hope to hear him again in more conventional repertoire.

This festival concert series, however, is one of those in which each artist

or group makes but a single appearance, which can seem wasteful especially

in the case of those who have travelled a long way to take part.

A few days later Arcadi Volodos, winner of the Gramophone Award of 1999, arrived in San Sebastian to play to a long sold-out house and excited anticipation. He did not reach the platform until twenty minutes late, preceded by bursts of slow hand-clapping; the Spaniards expect their concerts to begin promptly. There was an announcement requesting the audience's indulgence and to notify us that a Schubert sonata was to be replaced with some Rachmaninoff.

Volodos is a heavily built man who moves stiffly and with gravitas. He uses

an ordinary chair (as Schnabel used to) and began with an unusual opener

to familiarise himself with the instrument, the Brahms Variations in D

minor, transcribed from the slow movement of his 1st String

Sextet. This was followed immediately with a demolition of Schumann's

Kreisleriana. Its opening was vehement and brash, with heavy accentuation

and splattered with wrong notes, as were the subsequent fast sections. Although

played from memory, he sounded unsettled throughout, the music not sufficiently

assimilated for playing to the public, even at a seaside summer festival.

The quieter portions, given with head thrown back in contemplative manner,

exuded simulated sentiment rather than genuine feeling. A combination of

Russian training, a brilliant Steinway and the acoustically over-bright

650-seated Sala da Camera at the Kursaal all conspired against

Schumann!

Things fared better after the interval; the music maybe worse, its playing demonic and thrilling - in circus act terms! The group of mainly early Rachmaninoff including a Romance & a Serenade went well. He pulled out all the stops for Liszt's Ballade No 2 and ended the printed programme with his own arrangement of the 13th Hungarian Rhapsody, the composer's own version presumably being not difficult enough. I enjoyed his interminable string of encores, given to predictable insistence, including Moskowski and Scriabin, a wild conflation of tunes from Carmen and a delicious dance of Tchaikowsky's Sugar Plum Fairy.

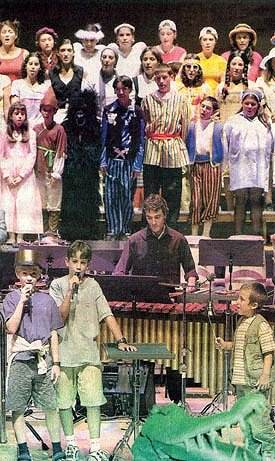

A FUN DAY FOR CHILDREN or how to build an audience for the future

The enlightened San Sebastian Festival management organises a children's

day every year. Sean &Heard joined two-to-twelve year olds with

their parents for an hour of fun. Their late afternoon concert was devised

and directed with ingenuity by Jesus Soldevilla. The professional Opus

111 Percussion Ensemble provided the backbone for brief introductions

to different kinds of music making.

The audience's attention was grabbed right at the start and gripped by the simulation of a tropical thunderstorm, with lighting/lightning effects in near total darkness, against the comforting and softening sounds of a children's choir. This provided not only a dramatic start but intuitively showed that music plays an important part in interpreting theatrical events and in literally underscoring particular interpretations. The children's choir was well trained, and dressed in fancy clothes to provide a sense of party fun and involvement with the children in the audience.

The different types of music making ranged from choral, popular, dance and film music to story-telling music theatre and were expertly linked by two amiable presenters modelled on familiar TV shows. The audience was not lectured to, but through clever presentation and involvement, some of it direct, they were introduced to some of the musical genres and some of the rituals surrounding concert hall music making. These children, both on and off-stage, are likely to want to come back again to the Kursaal as a place where good things happen.

CHORAL & ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS

The Bilbao Symphony Orchestra, playing in the Kursaal's main auditorium, took up the Homage to de Pablo theme and gave a good account of Luis de Pablo's fairly new, four movement violin concerto, a major addition to an uncrowded genre. It is a substantial half-hour concerto, requiring expressivity and virtuosity, both supplied in good measure by Agustin Leon Ara, who had given its première. Having known it through a tape recording of that performance, it was good to find that all the balance problems had been solved by the composer, and that the many original touches of orchestration allowed the solo part to come through easily; so many newer concertos sound as if they are composed with microphones and artificial balance in mind.

Ravel's ballet score Daphnis & Chloe, in its complete version with a large, wordless choir (the Sociedad Coral de Bilbao had far too little to do but did it well) fared less well in a somewhat rough performance, with climaxes congested and coarse, not helped by the over-bright acoustic of the main Kursaal auditorium, which is lined with flat, polished and highly reflective wood, with apparently little involvement between modern acousticians and the architect Moreno. That first impression of the hall itself had to be modified, however, after later experience.

Bach figured conspicuously, here as elsewhere this year. We heard the B minor Mass given by Philip Herreweghe and his Collegium Vocale Ghent, a specialist group which has earned highest regard on its travels and on CD. With only some twenty singers and a small complement of authentic period instruments, the sound was bright and vivid in the main concert hall of the Kursaal. An endearing feature of Collegium Vocale's concerts is their scrupulous tuning, their leader doing the rounds matching each player to her own violin.

The soloists were a well matched quartet, Deborah York and David Wilson-Johnson from UK, Jan Kobow (tenor) and Annette Markert, a true contralto with an evenly produced voice in all registers; her Agnus Dei towards the end was particularly moving. The performance had taken a lift earlier with her ecstatic, long lines in laudamus te and throughout the evening the dance basis of so much in Bach was always evident; the liquid flute & pizzicato strings accompanying soprano & tenor in Domine Deus maintaining the momentum. The bass draws the short stick in the B minor Mass, but David Wilson-Johnson despatched the awkward Quoniam tu manfully and the horrendously difficult horn obligatto was negotiated securely on natural horn with two bassoons, following which, apparently displaying some relief, Herreweghe took a surge forwards to finish the first half at a hell of a lick, displaying the virtuosity of his chorus and ensuring tumultuous applause for the interval. Herreweghe is an accelerando conductor, not given to any lingering; he seems to need to restrain himself from the urge to edge his musicians onwards.

This year's Bach celebrations have encouraged some symphony orchestras to dip their toes again into repertoire now normally forbidden to them. The strings of the WDR Radio Symphony Orchestra Cologne under the direction of Semyon Bychkov showed their quality in a rare airing of Mahler's arrangement of several pieces from the Suites, including the Air on the G string and the Badinerie from the 2nd suite, with some piquant pizzicatos to accompany the flute soloist, who was seriously outnumbered. Prokofiev's 1st violin concerto has never sounded better than in their performance with Franz Peter Zimmerman, whose singing violin was in perfect balance with the piquant orchestration in this most heart-warming of concertos. Vociferous applause gained a substantial encore of dazzling pyrotechnics, Paganini variations despatched with consummate ease and good humour.

Afterwards, a total change of mood with Shostakovich. His massive, brooding hour long 11th Symphony, The Year 1905 was written at a time when music was deemed to have a social and political impact in the Soviet Union, and the emotional content of such a work could not but have significance . Shostakovich's rendering in musical terms of reflections about those important events (and those in the Stalin era) is still very striking and harrowing. It transcends the specifics of the 1905 revolution and its consequences.

The sense of oppression, the resistances, the revolts, the threats, the backlash, the massacre, the questioning, the compassion, and resolution with integration into forward looking patterns, can still be applied to very many life situations. This 11th, not as often heard as many other Shostakovich symphonies, retains its emotional capacity to communicate something beyond musical patterns. Semyon Bychkov was as persuasive as possible with this daunting material, from the oppressive build up to the violent releases of tension in overwhelming climaxes with seven percussionists backing the large brass contingent, and he drew a searing performance from his orchestra which had great clarity as well as intensity. A memorable experience but not one I would wish to repeat for a very long time! But I look forward greatly to hearing again Bychkov and Cologne's magnificent radio orchestra, which was under-rated in the St Sebastian pricing structure and did not attract a full house.

Daniel Gatti, who brought the revitalised RPO to St Sebastian from London, confessed in his meeting with the press that his first love is composition. His 18-minute Divertimento for oboe and strings, receiving only its second performance as a curtain raiser before Mahler 6, pleased me better than the latter. It is not far from the English pastoral idiom, which the oboe readily evokes, and the language is fairly tonal and based on recognisable melody, accessible to all. He used a substantial string orchestra (but not the full complement assembled for Mahler) to good advantage, with well thought out scoring and good opportunities for the groups and their leaders to have their moments. The last movement had ample scope for displaying John Anderson's virtuosity. It should be heard in London - many orchestral conductors are closet composers, reluctant to try to impose themselves when financial constraints limit the scope for programming new music.

Regrettably, after the precision of ensemble and exemplary intonation of the Cologne orchestra the previous night the Mahler sixth was greatly disappointing. The 110-strong orchestra filled the stage and, in full flood for lengthy passages in this most densely scored of Mahler's works, it became noise without meaning, draining the capacity for emotional response to its lamentations and protestations. After the final climax of the first movement, it was exhausting to be thrown back into the maelstrom straightaway with this scherzo which offered no relief from intensity and decibels (the symphony, always problematic, is sometimes played with the slow movement second, which might have been better on this occasion). There were seven percussionists including the two timpanists, and full contingents of brass and winds, often playing in approximate unison and approximately in tune; one had an inescapable feeling that the players could not hear themselves in the Kursaal. Maybe never heard before in San Sebastian, the sixth was an unfortunate choice for this unforgiving auditorium, a stark contrast to the Royal Albert Hall in London, where the RPO has enjoyed a successful residency and gratifying revival of its fortunes.

For a final memory of music at St Sebastian, no experience could have been more memorable than to have heard again Lorin Maazel's famous account of Mahler's 2nd Symphony, this time with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and the local St Sebastian choral society, the Donastiako Orfeioa, which vindicated its involvement to resounding approbation, from their hushed entry to glorious full-throated tone for the roof-raising conclusion. Nor was there any let-down from the soloists after their long wait, Michelle DeYoung moving in Urlicht and Eva Johansson soaring to the heights in the last movement. Everything was in place and superbly balanced to ensure best theatrical effect in this dramatic hour and a half sequence of contrasted movements by a composer who was a great opera conductor, directed by a conductor who has the measure of its vast span.

The playing of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra put to rest any remaining doubts about the new hall's acoustics. The sound at the new Kursaal is bright, reverberation short and everything is heard with clinical clarity, which offers no hiding place for shortcomings. It can be punishing and unforgiving, and may benefit from some re-tuning by acousticians.

This meant that two orchestras which had known great days, and both reputed to be on course to regain their renowned status, were found wanting by S&H. The Bilbao orchestra did very well by Luis de Pablo in his skilfully orchestrated violin concerto, but the full orchestra was not up to the complexities and subtleties of Ravel's Daphnis & Chloe, its familiarity making comparisons inevitable. British readers must be disappointed that the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra has to be placed in the same bracket, sandwiched as they were between the lower-priced Cologne players and the Israelis, who were in top form in all departments and gave real festival playing of the highest order.

We are indebted to the San Sebastian festival Press Office for their hospitality and assistance during a memorable week in their beautiful city.

Peter & Alexa Woolf

Return to:

Return to: