Error processing SSI file

|

A synoptic survey by Tony Duggan Symphony No.2 The

'Resurrection' Each of the three "Wunderhorn" symphonies (2, 3 and 4) uses one of Mahlerís song settings from that collection of German folk poetry as a kind of "beating heart" to the whole work. Each of the three symphonies also has strong programmatic elements. In the case of the Second and Third, there were detailed programmes that Mahler later tried to discard rather as a builder might dispose of scaffolding. But the programmes remain to study and light the way through these huge works. The Second was composed between 1888 and 1894 and this span of years indicates its difficult birth. The long first movement began as a standalone symphonic poem based on a novel sonata-form structure with, to put it simply, two development sections. It was called "Todtenfeier" ("Funeral Rites") and provided the rock on which Mahler would subsequently build the rest as his imagination fed his creativity. By the time he had finished the whole five movement symphony, helped towards the end out of a creative block by hearing a setting of Klopstock's Resurrection Ode at the funeral of the conductor Von Bülow, Mahler had created an audacious piece of concert hall theatre, part choral symphony, part oratorio, that delved in the most spectacular fashion into nothing less than the whole question of immortality. Using immense forces he ended up trying to dramatise in music the struggle of mankind towards eternal salvation. As he himself said: What was the purpose of struggling through life whilst alive? After death would any meaning for life be revealed? Was there salvation or damnation awaiting? For the conductor the challenge is to unite this diverse structure both musically and emotionally and it is one which prompts a diverse set of responses. The Second has the distinction of being the first ever Mahler symphony to be recorded "complete". Though I do use that word with some care and you will soon see why. The recording was made around 1924 by Berlin State Opera forces conducted by Oscar Fried. Fried knew Mahler quite well, admired him, and it seems Mahler thought quite highly of Fried. Mahler was even present at a performance Fried gave of the Second in Berlin where the off-stage band was conducted by a young whippersnapper called Otto Klemperer and was complimentary to both men. Surely this should make the recording Fried made in the 1920s of the highest value? Well, no. I have to say I have never shared the reverence many Mahlerites feel for this fabled recording. I even wonder whether some of its cult status springs from the fact that it was unavailable for so many years, only re-appearing since its original release in the 1980s on an LP transfer by Pearl Opal. It does have some interest and it does have a little to tell us, but I really believe we should be careful in drawing too many conclusions from it. It was made just before electrical recording became the norm and so the considerable drawbacks of the acoustic process are all too obvious and all too limiting. Remember, in order to bring off what remains a remarkable achievement for the time the orchestra had to be thinned down drastically, the music re-scored to cope with that (including a bass tuba to fill out the basses) and what musicians and singers were left had then to be sardine-crammed together in front of an immense recording horn whose cutting stylus would scratch out whatever came through on to the wax disc on the turntable. Not so much Mahler by Fried as "Fried Mahler". All of that before you have to take into account the need for breaking off every four minutes to change the discs. This means that what we do hear can only be a pale impression of what Friedís performance of Mahlerís Second might have sounded like in the concert hall. Not enough to draw any firm conclusions in anything other than some aspects of phrasing and tempo and general enthusiasm. Ward Marston has done his usual sterling best with commercial pressings for Naxos (8.110152-53), but this cannot alter the fact that what you will hear is constricted, in limited sound, with pitch that is indeterminate and playing with lots of mistakes. MahlerĎs wonderful scoring merely hovers like a phantom in your mind. I am prepared to admit that, using imagination and good knowledge of the work, I can use this recording to bring myself to believe that Friedís performance in the concert hall might have indeed been impressive. Other than that this is really the audio equivalent of watching that grainy, jumpy, flawed and fuzzy monochrome short film footage of the funeral of Edward VII in 1910 passing by a single hand-cranked camera and then trying to imagine what it might have looked like if high definition colour TV cameras had been present on the entire journey from palace to cathedral. A big leap of imagination, not to mention faith, is needed. Have it in your collection by all means. There are in the set some other remarkable and better sounding electrical recordings of pioneering Mahler performances. But curb your enthusiasm for the symphony recording, please.

The second movement should contrast with the first. In fact, Mahler was so concerned about this that he asks for a five minute pause. Here Mahler is trying to show an interlude in the life of the person deceased in the first movement. Under Walter it doesn't quite contrast as much as it can. A fine reading, however, with the air of a veiled dance and dance is what does lie behind this with Mahler's favourite ländler lurking magically subdued. There is a lifetime's experience in Walter's reading again. No sense of having to force a personality on the music's dark lyricism and with lower strings continuing the purpled-hued qualities of the first movement. When the music becomes more passionate and striving Walter sees even more relationship between this and the first movement. Even the closing section, with pizzicato strings, brings a whispered, phantom-like quality. A triumph of form balanced with content. The third movement is where all the irony and bitterness inherent in asking the great questions of life whose conundrum Mahler is trying to crack come to the fore, or they should. Based on Mahler's earlier setting of the Wunderhorn song about Saint Francis preaching a sermon to birds and fishes who remain uncomprehending and unchanged by the experience, there should be an air of futility and illogic about it: a mocking treadmill punctuated by the clacking of the rute with the world seen through a concave mirror, as Mahler described it. This is where despair and desperation should enter the soul. Fine though Walter is, he doesn't lift us all that much from the grim, elegiac quality we have noticed in his reading. There are details highlighted, but the rhythms and interjections can be made so much more of than here. The brass outbursts that spin the music along are a mite restrained too. There is a lovely trumpet solo at the heart of this movement, however, and under Walter this emerges sweet and golden but, again, more might be made of its crucial role as a vision of nostalgic hope in the middle of what ought to be a horrible, grinding experience. Towards the end we come to the emotional core of the movement, one of the crucial "way points" of the work, what Mahler refers to as a "cry of disgust". Under Walter this seems robbed of a greater power. More a cry of distaste than disgust. In the fourth movement we hear Maureen Forrester, one of the greatest Mahler singers, and her presence is one of this recording's virtues, as also is the restrained way Walter accompanies her, prayerful and tender, as hope in the form of the Wunderhorn poem "Urlicht" ("Primal Light") about entreating an Angel to light the way to God prepares us for the cataclysm to come in the fifth movement where the drama of resurrection of the whole of mankind is played out, moved from the personal to the universal. This immense series of tableaux takes us on a journey from death to resurrection and it is here Mahler's astounding imagination finally shakes itself free and goes for broke. The huge movement, where any idea of symphonic form finally is abandoned, must carry a dramatic charge, the strength to maintain itself in moments of vast repose, and encompass a real sense of huge events developing around us in an ordered and yet unorderly fashion. No apologies must be made by the conductor. It must move, inspire, terrify, entertain, go to our very deepest centres and bring resolution and consolation. Under Walter there is a drastic opening with fine lower strings underpinning. The first outburst dies away to leave us with the distant horn calling as "the voice crying in the wilderness" and here Walter's sense of charged nostalgia is never more in evidence than in the way he builds gradually with a superb sense of architecture towards the first announcement of the crucial "Oh Glaube" ("Oh believe") theme that will keep coming back at strategic points to haunt us as an entreaty. Its first appearance is rather smoothly taken, more stress on symphonic growth. The vast climax on fanfares that marks the close of the first section arrives with weight and power but doesn't overwhelm as it should. It's as if Walter is holding back. This moment can really thrill under the right conductor but with Walter it merely impresses. There then follow two huge crescendi on percussion and brass that portray the bursting open of all the graves of mankind's dead. Under Walter they are not really long enough, or loud enough, to carry the seismic shock built into them and so are slightly disappointing when you know what can be done with them. The great march that follows is meant to portray the trooping to glory of the souls of mankind and this is paced about right here but doesn't carry quite as much terrifying power as it should and can be made to. It builds to a good climax, though. In the reprise of the "O Glaube" theme that follows Mahler's aural imagination tests the performance even further as we now hear an off-stage brass band crashing out a manic march. They can make a terrific effect but here not as much and the effect is rather earthbound, as though a limit to terror has been imposed. The next climax, a stunning collapse where the fabric of Mahler's vision seems set to tear itself asunder, gives Walter a chance to take the terror to what is his own limit which is, I have to say, some way short of others. We have then arrived at what Mahler calls the "Grosse appell" ("The Great Call") where the off-stage brass sound fanfares from heaven against the sound of flutes playing the part of a nightingale, the bird of death, as the last sound from earthly life left behind. Under Walter the trumpets sound more like barracks buglers (which in other symphonies would sound ideal) than heavenly hosts and the whole passage would have been better if it had been given more space. Now the chorus enter, intoning Klopstock's Resurrection Ode, the hearing of which, in another musical setting, unlocked the block that had descended on Mahler. There is a wonderfully nostalgic solo trumpet after the entry of the soprano, stressing again lyricism and nostalgia over drama and terror, and Walter makes much of this. It must, however, be obvious that, to me, it's his interpretation of this movement that symbolises best his general approach: spiritual over human, lyrical over dramatic, vigour over terror, symphony over quasi-operatic. One valid way of seeing this work but not, I believe, the whole story. This impression is carried forward to the final chorus, "Aufersteh'n" ("Rise again"), which under Walter stresses a hymn-like quality and therefore a certainty that is palpable and touching, yet with no real sense that what we are being given has been hard won and I think that, for this work to succeed completely, that is more inappropriate. It's as if for Bruno Walter the end was there to start with and all we had to do was arrive to be admitted. Was Walter too certain of himself? I think he was. Just as I'm equally sure that Mahler wasn't and the implications of this are deep and profound for this work and will come back again and again as we discuss other versions. Walter himself once said that Mahler spent his life searching for God but never found him. He doesn't seem to have brought that idea into his reading of this work, to these ears at least. The playing of the NYPO is exemplary with a depth of experience that can be heard in every bar. The sound is early stereo from the late 1950s and perfectly acceptable in itself. For those who mind, however, they might find it a little limited in range and detail, though the balance is always spot on. My view of this Walter recording may seem harsher than it is as I do regard it as one of the truly essential recordings. My disagreement with it is more intellectual as I believe there is more to be gleaned from this work and the fact that Walter does not do so is not a reflection of any inadequacies on his part, merely a reflection of the kind of man and artist he was, especially at that time of his life.

In the fourth movement "Urlicht" Hilde Rössl-Majdan is not as dark-toned as Maureen Forrester but just as "inner". Klemperer also refuses to linger here and the fifth movement bursts in with a dark drama and Brucknerian sense of colour in the brass. A mood which continues through the voice in the wilderness passage. Klemperer seems to have a greater sense of the diverse structure of this movement because each succeeding section leading to the great percussion crescendi are paced separately with a sense of developing drama and a feeling of trepidation. The wonderful passage of the brass climaxes before the two crescendi is grand and imposing, more so than under Walter for all the latter's spiritual approach. Klemperer's trenchancy, his sharper focus, suits this music better since it makes it more immediate. The percussion crescendi are made more of by Klemperer and the same is true of the central march where Klemperer was always slower than anyone else and, for many, this can be a problem. To me his sense of grim grandeur is absolutely right. After all, the march of the dead from their graves to glory should hardly sound like a one hundred metre dash. This added trenchancy also becomes hypnotic and the cumulative effect works to the extent that, by the climax where the world collapses in on us, the tension has become unbearable. It also allows Klemperer to bring out inner detailing on woodwinds others miss and he always was one to balance and terrace different sections, woodwind especially, closer in. Again, all this has the effect of making the music more immediate, accentuating the sense of struggle and conflict, humanity tested prior to deliverance, that you miss with Walter and those who emulate him. The passage during which the "O glaube" motive is heard on trombone with the off-strange band crashing away is brought off magnificently by Klemperer with a real sense of neurotic disjunction and Mahler's exploration of acoustic space exploited to the full. The "Grosse Appell" follows a superb preparation with fanfares well distanced and note the soft drum roll, audible where with other recordings it is not. The final "Aufersteh'n" is more muscular than under Walter and gives a final sense of perspective to the spirituality. Taken with the rest of Klemperer's interpretation, this confirms the hard-won goal by a man of action and experience rather than an easily achieved one by a devout believer. It moves us but, crucially, it inspires us by its sense of humanity. The sound recording is almost the same vintage as the Walter and shares many of its shortcomings in being rather limited now. It is, however, strong on detail and in conveying the precise kind of sound Klemperer preferred. The playing of the orchestra is not without a problem or two but the rough-hewed quality of what Klemperer is trying to project may be helped in this. In an interview Klemperer maintained that the difference between himself and Walter was that Walter was a "moralist" whereas he was an "immoralist". A half-joke, perhaps, but there is more than a grain of truth there and I believe comparison of their respective Mahler Seconds gives clues as to what he might have meant. Walter's simpler, more lyrical approach, stresses spirituality and faith, certainties that always run beneath and which, in the end, win out. Klemperer's more austere sound palette, his leaning towards the more ironic, workaday elements, his regard to the slightly "off-beat" and his willingness to press on when others relax (the march in the fifth movement the exception that proves the rule) suggests he wishes to stress more the uncertainties that run beneath the work and, in spite of which, we win through in the end. To put it another way Walter takes Mahler's apparent certainty of deliverance at face value where Klemperer at least asks questions and, in so doing, makes this work more accessible, more involving and ultimately more moving because it is as concerned as much with what we leave behind as with what we might inherit in the world to come. Klemperer and Walter, as ever, provide in their different approach to Mahler a fascinating dichotomy, one which absorbs and stimulates. For that reason both recordings should be in every Mahlerite's collection. Both suffer somewhat from being studio made, however, as it has always struck me that this symphony, along with the Eighth, cries out for "live" concert recording. Maybe this is music that ought only to be heard in the concert hall since its special brand of human involvement can only be conveyed at personal proximity. But recordings are what we are discussing and so is it possible to reproduce something of the "live" experience in your own home? And is it possible to unite the two approaches Walter and Klemperer exemplify? In fact, I think this is what most conductors do, probably without realising it, but with most leaning towards Walter and his "at face value" sense of the deliverance that is achieved.

In the second movement Kubelik is well aware of the need for contrast and delivers one of the most distinctively characterful versions available. A real interlude as well as a contrast. He takes care of this movement, especially in the central section when the music is more animated. Following this, precise timpani shatter the mood and the pulse quickens for the third movement. This is a totally different view to Klemperer or Walter. By speeding up and not making much of the off-beat qualities Kubelik seems to play down the earthy ironies in favour of something more fleet of foot. In the animated sections, when the brass propels the music on, there is a feeling of perpetual motion about it, the endless roundabout of life, that is refreshing. The solo trumpeter is rather anonymous but fits with the general conception, though I found this a minor disappointment. But not the outburst at the cry of disgust which arrives like a helter skelter into chaos, helped by the quick tempo and again marks out Kubelik's reading as one that is out on its own. Norma Proctor is suitably prayer-like in "Urlicht" and Kubelik suitably held back so this is a fine preparation for what is to come with the spiritual side stressed. The start of the fifth movement has all the drama and majesty you could want with some wonderful shudders on the lower strings. The "voice in wilderness" in suitably imposing and the delicacy of horns over harps and woodwinds, and the flutterings of violins and deep growls from basses and contrabassoons with bass drum, shows Kubelik is anxious to bring out every unique sound. There is a pull on the music that makes its own drama, a genuine striving upwards which the conductor is not forcing on the music but bringing out what is there. When we do arrive at the great climax of fanfares before the percussion crescendi there has been as much inevitability in it as with Klemperer but with that touch more spiritual rapture we found with Walter. Though the "O Glaube" material has real desperation. The grave-busting percussion crescendi are rather short-changed and the subsequent march is quick, but in the overall context of Kubelik's tempo it still tells. I miss Klemperer's trenchancy but I admire Kubelik's sense of architecture and his piercing Bavarian brass are thrilling. There is also a great sense of release here. You sense the liberation of the souls rather than their sense of being the previously dead. The off-stage bands may lack Klemperer's unhinged quality but note the weird vibrato on the trombone as it intones the "O Glaube" motive and the Grosse Appell" is a real call to attention. There is a sense of rapture following the choral entry and you can hear all departments of the orchestra well too. Kubelik relaxes his tempo here and there is a definite feeling of contrast between not just this part of the movement and the preceding, but this part of the whole symphony and the rest. It's as if a Rubicon has been passed and is another example of the conductor generating the symphony's own drama from within so that the sharpness of focus in "Aufersteh'n" maintains the momentum. It doesn't linger for effect but delivers a real visceral charge, liberating again. The recorded sound is rich though it favours top frequencies within a generous, but not over generous, acoustic. Is it studio bound nevertheless? Of course, up to a point, and it indicates again that maybe this work always needs that extra charge of "live" performance. The irony is that since my first version of this survey a "live" recording of the Second Symphony conducted by Kubelik has actually appeared on the Audite label (23.402) but I still wouldnít prefer it over his DG studio version. Uniquely on this occasion I donít think Kubelik reproduces as memorable a performance for the audience as he did for the studio microphones. My preference for "live" recordings in this symphony especially still does not blind me to versions made in the studio when their virtues are more apparent, as in this case. My advice concerning Kubelik in this symphony is to stick to the DG version. There is more spontaneity and there is more of that sense of the Wunderhorn world than there is in the "live" version and that is what makes the DG version one for the shelf. This also applies to the recordings of the Second conducted by Claudio Abbado. His first commercial recording was made in 1976 with the Chicago Symphony on DG (453 037-2 coupled with his Vienna Fourth) in the studio and is, in my view, preferable to both of his "live" remakes with the Vienna Philharmonic (DG 4399532) and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra (DG 4775082 for the CD and TDK DVCOMS2 for the DVD). I cannot be persuaded that Abbado's interpretation has gained anything in subsequent years - in fact quite the opposite - to make the "live" element of real value. The Vienna performance is simply boring and the Lucerne, whilst a distinct improvement, is too self-conscious to deliver the spontaneity that all the drama demands. This is an orchestra specially formed for the festival out of "all-star" players. But "all star" individuals do not necessarily an "all-star" band make or breathe with the kind of corporate breath that the Chicagoans have in abundance. In Chicago Abbado is broader in the first movement than Klemperer so there is greater weight but still a significant sense of forward momentum: two necessities in the first movement. There is also a spacious acoustic to the recording which adds to the sense of an epic journey. At the start of the first development the ascending theme brings a real sense of vast distances, veiled and restrained, limpid even, and alerts us to Abbado's exploitation of dynamic contrasts that mark this recording out. This first movement is also a more episodic reading than the ones dealt with so far and the test will be whether it all hangs together. As the first development closes Abbado shows himself aware of the seamier side of the sound and is aided by superb playing from the CSO, completely different to the way they sounded at that time under Solti. This is one of the best played recordings on the market. As the recapitulation approaches Abbado's sense of architecture and drama proves matchless. The climax itself arrives with thunderous inevitability, brassy and powerful, and when the music picks itself up Abbado's sense of architecture is there again. The coda creeps up and gathers with some great playing again which gives Abbado a free rein and bodes well for the rest. Klemperer's particular sense of the grotesque and absolute imperative of pressing ahead may be missing but there is a fine sense of mystic tension to compensate. After the kind of first movement we have heard, making a contrast with the second movement is easier and Abbado delivers a real Andante, distinguished again by some wonderful string playing with every slide and phrase carefully realised. Abbado also sings the beautiful cello line before the more animated central section. This care for detail and for a singing line distinguishes this performance greatly. Bruno Walter once described the third movement as "spectral" and at the start this is the impression with Abbado. Don't expect Klemperer's bitter sarcasm, but Abbado clearly has something different to say and the range of colour the CSO is capable of more than compensates. The impression of spectral quality in earlier passages is accentuated when the trumpets and brass burst out in the central section like a shaft of light and the music also picks up in energy to the cry of disgust which is delivered with plenty of spirit. Though notice how the spectral quality returns at the close. The "Urlicht" is slow and intense with a feeling of a "song of the night" which fits well with spectral quality that precedes it and will provide great contrast for what is to come. Abbado doesn't overwhelm us at the start of the fifth movement and could have been a little more earth-shaking, but maybe he is saving something up. There is delicacy from the orchestra in the passage that follows the first off-stage call with every detail of the celestial mood painting caught by the fine recording and sustained over a slower tempi than the others so far dealt with. The sheer beauty of this passage is deeply moving, every sound savoured, weighed and sifted. It's almost hypnotic when the distant horn comes back to accompany. The first appearance of "O glaube" maintains the mood of expectation also and I especially admire a significant pause before the solemn brass enter to build for the first great climax which, when it arrives and the fanfares break out, is stunning. Fabulous brass and the contrast with what has gone could not be greater. The percussion crescendi are effective (why do so few conductors really sustain them longer?) and the great march is perfectly paced up to the moment when the music collapses in chaos and we hear a degree of desperation transfused along with an appropriate ugliness. After a beautifully distanced Grosse Appell with sweet -toned flutes, the chorus's soft singing stresses Abbado's hymn-like view of the chorale, sweetly comforting and confirms this as a performance more in the Walter tradition. I was pleasantly surprised at the way Abbado refuses to give in to the moment during "Aufersteh'n". This final hymn might underwhelm people who expect a great charge of emotion here but Abbado doesn't see it like that. Whilst I feel he has stressed the certainties in the work his noble restraint at the end adds a serenity that is refreshing. So I think Abbado's recording favours the Walter approach in being anxious to stress spirituality couched through sweet nostalgia, but at the end he maintains a healthy circumspection. Where he also differs from Walter and, I think, scores over him is his and his orchestra's ability to really bring out the immense contrasts that are possible in this work, further marked by his tempi which are overall slower than Klempererís but which sustain by Abbado's ear for detail and that of his orchestra and engineers. Like all studio recordings there is a sense of earth-boundness, but it's not as marked as with some and that is a great tribute. Unquestionably this is one of the finest studio recordings available, though it has to be said that there may be some who need more drama, more hands-on qualities, than Abbado is prepared to give.

The opening string passage of the second movement is consciously moulded, with every dynamic brought out as though in a pin-sharp colour photograph. There is no denying a certain amount of conscious moulding adds to the music, but when the double basses suddenly leap out from the texture you begin to realise the hand is too strong. Then in the animated central section we are almost back to the shifting and thrusting maelstrom of the first movement. This is drama in the extreme again and too muscular in what should be a rest from struggles past and struggles to come. Solti's approach works better in the third movement. There are some lovely woodwind interjections, great col legno snaps of wood on strings and the dynamic contrasts bring out well the sourness. The middle section is superbly cutting also and profoundly dramatic with piercing trumpets and a feeling of the world spinning out of control. In the fourth movement "Urlicht" Helen Watts may be the best mezzo soloist of all and she preludes the fifth movement unforgettably. Here the opening has a terrific sense of release and heralds the best of Solti's recording. He's very aware of the theatrical nature of the movement. Never more so than in the passage near the start of the voice in the wilderness passage a few minutes in where appropriate tension is palpable. With the first appearance of "Oh glaube" there is a firm architectural control also with each step firmly marked and the tension ratcheted up as we approach the solemn announcement on brass that will explode into fanfares. This is held back just enough to sound really portentous with a wonderful "luftpause" before the low brass intone the chorale and only when the fanfares and brass bursts out with cymbals is the picture complete. The great percussion crescendi to herald the march are like aural flame-throwers and the march itself, though on the quicker side, because of Solti's concern for clarity, especially in the strings, maintains considerable weight. I also liked his handling of woodwind and brass. Shrieking high woodwind and blazing horns are especially fine but the collapse at the end is a disappointment. I've heard more sense of disintegration but much is redeemed by the Grosse Appell which the Decca engineers in the old Kingsway Hall managed with breathtaking ease. Solti despatches "Aufersteh'n" with too much efficiency to my liking. There's a calculated feel to the singing and to the orchestral coda. At the end, Solti, as so often, seems too interested in delivering a well-engineered piece of machinery, impressive in its itself but failing to reach deep. What he does do in the whole work is transcend to a certain extent any studio-bound feeling. He does this by creating his own brand of tension but one which I think fails to take into account every aspect of the work. This is a fine recording of a particular interpretation and there are times when I could think that it would do very well, but there is much more to be gained from this music. I include it here because as a visceral experience it still thrills and moves.

The second movement shows up the fact that Scherchen doesn't have a large body of strings and so inadequacies in the playing are exposed. The underlying tempo is slow but it's well sustained and the music never flags or wears, and Scherchen is determined to maintain his dark-grained tread here also. Then in the third movement it's remarkable how close Scherchen's reading is to Klemperer's. What he doesn't have is Klemperer's mordant wit. What he does have is an impression of pinning down the music like laboratory specimen and he is sufficiently unnerving to make this music so memorable and such a contrast to what has gone that it's hard to imagine it interpreted better. You really do need a different set of listening criteria with this man, the rule book, if there is one, must be discarded. He speeds up for the climax and so gives the kaleidoscopic feel an extra twist and his cry of disgust really impacts. In the fourth movement Lucretia West sustains "Urlicht" heroically at this slow tempo but in the central section a speeding-up occurs which makes this a unique and refreshing rendition of this movement - a movement of two halves. There is a superb start to the fifth movement where the broadness of Scherchen's approach pays rich dividends. Note the pauses he observes, especially before the first off-stage call. This shows a great sense of theatre, not least in the grand vistas of the great climax prior to the percussion crescendi. The march that follows gives Scherchen the chance to make the movement take wing. I don't usually like too quick a march but after what has gone this gives a splendid sense of liberation. In the "Grosse Appell" note the bass drum beneath and the close brass making this passage very exciting. It's a pity the chorus are too loud at their first entry, but there's a lyrical feel to the music and that continues into "Aufersteh'n" which is taken at a very slow pace indeed to the extent that you wonder how the chorus didn't die from suffocation. It's impressive, excessive, obsessive, but maybe this is what is needed to inject drama into a studio recording. I do treasure Scherchen's interpretation. It's one of those unique pieces of Mahler conducting whose mould, if it ever had one, was broken as soon as it was made. Scherchen was his own man who could infuriate and inspire, sometimes all in the same performance. But whatever he did he was never dull and that counts for a lot in these days of designer maestri turning out Mahler recordings as though from some assembly line staffed by robots. Is this sufficient reason to recommend a recording of Scherchen's for the library? No, I don't think it is. What he does is deliver a performance that has insights that no one else's does and therefore it demands its place in this survey. The main drawback is the sheer scale with tempi and dynamics and expression, of such extremes they would try the patience of the greatest Mahlerite. However, Scherchen does manage in the confines of a studio recording to suggest the idea of a "live" performance and that's something which I believe is a recommendation in itself. Mahlerite Deryck Barker has called this the most "dangerous" interpretation of the Second Symphony and I can see what he means. As an exercise in excess it is unsurpassed, but what is remarkable is that within that excess there burns a sharp and cool intellect. What ever Hermann Scherchen does he does in the service of the music, never himself.

There is a nice moderate tempo for the start of the second movement and a warm tone for the strings. Rattle marks well the contrast between this and the first movement so this emerges as a real intermezzo with some lovely "old world" slides in the strings. The central section is quicker and more challenging. No conductor in this survey, save Klemperer or Walter, make quite so much of this movement, its sense of yearning and its busily worried quality. No other injects quite as much control over it either. Rattle is a controlling musician. Indeed I feel that since this recording he has become a "control freak" micro-managing to a surprising degree. In the third movement he doesn't have Klemperer's sense of irony, or Scherchen's analytic quality, but he does make the movement work. The rute is too soft, though, which is surprising, but the brass outbursts are magnificent, propelling the music forward, shafts of light breaking through the dark clouds. This is a performance of great contrasts so the slowing down for the trumpet solo makes for a nostalgic interlude, illustrating Rattle's grip on the many-sided nature of this work and of being able to switch moods in the twinkling of an eye. The descent to the cry of disgust is as superbly handled as the corresponding section in the first movement and again the same sense of the need to find the real climax as the cry itself caps the movement as the real core. It is as if this cry of disgust was necessary for purgation before we enter into transcendence. No conductor delivers that feeling but Rattle - a truly unique insight. In "Urlicht" we are in the presence of Janet Baker and her superb musicianship with Rattle's support carries all before it. Note the exotica of the central section, straight out of turn-of-the-century Vienna. There then follows a stunning opening to one of the finest recordings of the fifth movement ever: expectant, epic, grand and aware of every strand as the music dies down for the call in the wilderness. There is a feeling of huge distances and as the music goes through its various episodes. The impression is of a series of steps being mounted, huge plateaux where we and Mahler are dwarfed yet never obscured. Notice how Rattle seems to change mood at the first appearance of the "Oh glaube" motive. The climax prior to the percussion crescendi heralding the march starts from solemn lower brass, played slowly like a Bruckner chorale, then mounts to a climax that is shattering. Again the sense of knowing where each real climax lies and paying it all the attention it needs must be noted. Not surprisingly Rattle gives the percussion crescendi the longest span possible but the march is perfectly paced, powerful yet, like Klemperer, sapping of energy. Though only Klemperer really gives it the trenchant sense of great weight being dragged along - our sins, no doubt. The approach to the climax of the march, where the music collapses in on itself, almost equals Klemperer's sense of exhaustion here and the collapse itself almost floors you. In the section that follows I was impressed by the ripe trombone solo with the second "Oh Glaube" as well as the tension carried over from collapse. The off-stage band sound like a gang of demons snapping at our feet. Then there is some lovely soft singing from the choir with every word clear and again the sense of another page having turned. But there are still questions as Janet Baker intones "O Glaube". There is a feeling of arrival as the last section begins and the final resurrection hymn is broadly sung with a grand, solid certainty that we are entering paradise. The splendid sound recording copes superbly with everything Mahler throws at it - percussion, brass, organ and the final pages leave you breathless with awe. The playing of the orchestra is as good as any and better than most, and overall this performance has great reach, grandeur, excitement and involvement. Maybe it lacks Klemperer's sense of a hard struggle, as well as his sense of the grotesque, the earthly qualities. But it has an epic reach beyond Klemperer that goes a long way to compensate. Of all the studio recordings I have dealt with this one by Simon Rattle comes closest to the sounding as if it is being given "live" and I believe is as worthy as Walter's to stand along Klemperer as one of the greatest interpretations ever recorded: the other side of the coin, another "moralist" to Klemperer's "immoralist".

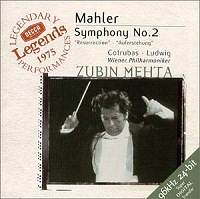

There are conductors

who can put lead in the Mahler pencil

of the Vienna Philharmonic. Leonard

Bernstein was certainly one of them

and in this work Zubin Mehta another.

Even though Mehtaís The last movement bursts on us well, though a little more richness from the recording again would have helped. However, one positive aspect of the sound recording now becomes apparent in the distant horn calls - Mahlerís "voice in the wilderness" - that follows. The placing of Mahlerís directional effects Ė offstage horn calls and band music Ė is brilliantly done in this movement with great care taken to create an aural stage between our speakers that adds lustre to Mehtaís performance. His account of the march (220-88) sees him pressing forward but there is never any sense of rush. The weight in the music is there, but I donít think he achieves the sense of explosive tension that can build up as the movement reaches its two great climaxes, the second preceded by that remarkable passage with the offstage band crashing away, capping the first. Again Klemperer pulls it off, so does Bernstein and Rattle. But I do like the way Mehta clears the scene with some magical string playing prior to the "Grosse Appell" where offstage fanfares sound against on-stage flutes signifying the last sound hear on earth prior to judgement day. This is balanced superbly by the Decca engineers working in their old haunt of the Sofiensaal in Vienna. One minor gripe here and itís something that has always annoyed me in this recording. A double bar line separates the last chord of the flute and piccolo on stage and the brass off stage from the entry of the chorus a capella. Mehta ignores this and has his chorus enter at the moment the instruments stop playing. Apart from ignoring Mahlerís marking this spoils the effect Mahler was clearly aiming for and I cannot understand why Mehta did this. The chorus sings magnificently with some wonderful basses especially impressive. Mehtaís sense of theatre returns as he proceeds to the "Resurrection" coda that maintains the symphonic argument but is grand and reflective in equal measure. This is a fine studio version in the Walter tradition in that he takes everything at face value and is none the worse for that. The sound is not without problems. Everything is contained with ease but thereís a slight "manufactured" quality, which isnít too obtrusive and certainly benefits from the superb placing of effects. Unlike with Kaplan, the presence of the Vienna Philharmonic is a real plus. There is another recording of this work with the Vienna Philharmonic, this time conducted by Lorin Maazel (Sony SB2K89784). Its sprawling grandiloquence gives rise to some lumbering tempi at times and when allied to some odd recording balances it is ruled out completely. Whilst I am wielding my axe I must also chop out the recording by Oleg Caetani (Arts 47600-2). He is certainly a fine conductor and I think I can even discern a fine conception behind this performance. The problem is the orchestra, which are clearly second rate and manage to deliver a third rate performance for him. No composer exposes poor playing like Mahler does and this recording proves that in spades.

Recording quality improves from the second movement on. That hard, "toppy" edge in the first movement has lessened and there is more space with the orchestra heard to better effect. Tennstedtís conception of the second movement is dark and intense, autumnal in its colouring. Then in the third movement I was reminded of how many conductors miss the special quality of this music with its peculiar atmosphere because with Tennstedt we can hear the strange sound of the rute and the woodwind shrieking and chirruping just as they should. He can also suggest the elegiac quality beneath the weirdness. He presses quite a fast overall tempo, though, especially in the brass-led interjections. After this the Urlicht fourth movement is intensely slow with Doris Soffel tested to the limit and beyond. I suppose the line is sustained but only just. Such an interpretation is in keeping with Tennstedtís typically intense performance and you hear this best exemplified in the last movement where he sustains the line through the disparate sections in spite of the fact that he continues with his zeal for exploring opposites. He opens the last movement with a vigorous and apocalyptic rending of the sky and then delivers a tense reading of the passage 43-191 that is portentous with very little sense of self-indulgence. There is a real sense of architecture here as well as a fine grasp of the musicís special colours with the London Philharmonic playing with distinction for a conductor they deeply admired. The brass is almost Brucknerian at times, deep and resonant, as they intone the Dies Irae prior to the wonderful outburst prior to the percussion crescendi at 191. It is a pity Tennstedt cannot resist taking the big march too fast, though. It is certainly exciting, invigorating even, which I suppose being liberated from your grave would be. But I really think something more trenchant than this is needed, well though the orchestra plays for the almost manic quality they bring to Tennstedtís vision. That latter aspect is attended to well at the passage for the offstage band but again, at the "collapse climax" prior to the Grosse Appell, the recording betrays that glassy top noticed in the first movement. Fanfares are placed closer than usual, accentuating this as a studio production, but so is Rattleís recording on EMI and that manages remarkable atmosphere here. Tennstedt has no doubts about the music from here on. He takes it at face value as a noble deliverance from sin and pain and there is much to be admired in that. The end is surprising for being unsentimental, even muscular, and I found it exhilarating and optimistic. The recordingís "close in" quality does the chorus no favours, though. As has been the case right through, at the end there is a slightly calculated quality that would perhaps have been alleviated by recording one of the concert performances Tennstedt gave at the time. This was still the era of "studio is best" which is a pity because Tennstedt, whatever oneís attitude towards his work, (and I was never one of his greatest admirers), always was able convey his own mix of romantic flair and dramatic energy better in the concert hall. I well remember how eagerly people awaited this recording. Having heard a broadcast of the concert prior to it I remember being disappointed I didnít have a souvenir of that. Taking the reservations of recording quality into account, and not hiding the fact that this kind of performance is not one I personally agree with, I do still rate this. I admire and enjoy conductors of Mahler who are committed even if itís to a view I do not have entire sympathy with. Tennstedtís admirers will already own it, of course, but there are always new converts to the cause waiting. Others should give it active consideration.

There is a wide and deep opening to the last movement. In moments like this that the recording really delivers. The passage 43-97 where Mahler carefully assembles his material like a set of building bricks finds Litton superbly aware of the fantasy inherent. In fact this passage confirms for me Littonís strength in that department. The feeling I have is that the performance does improve from here on with a greater sense of abandonment, less the feeling of not wishing to offend. When the "Oh glaube" material comes at 97-41, though there is sufficient pleading quality, I could have done with more drama, still more caution thrown to the wind. Some excellent deep brass then prepare for the great outburst 162-190 which really storms the heights with the recording catching the whole spectrum superbly. This is followed by the two great percussion crescendi that fill out the large acoustic space and in the great march we can at last hear the virtues of the spacious soundstage at its best. Iím convinced this has hidden some of the intimate music before but now it really comes into its own. What a superbly truculent march Litton and the orchestra give us here too, really digging in for the long haul, nearer to Klemperer. Full marks to Litton from me for realising this is a marathon and not a sprint. The collapse at 324 is huge and the tension sustained well through the passage that follows with the off-stage band excellently placed to make the novel effect Mahler surely intended. Litton keeps this passage pressing forward so when the second clinching "collapse climax" arrives we are ready and grateful for the respite that arrives. Again the brass are well-placed off-stage for the fanfares in the Grosse Appell and again Littonís sense of fantasy is well to the fore with his filigree painting of the bird flutes around them as good as any you will hear. The chorus is then not indulged and they nobly sing their first entry placed perfectly in the sound stage. The two excellent soloists are well positioned too and, like the chorus, sing superbly. The great coda begins with a real flourish and builds to a grand and noble climax with the organ beautifully in the texture, sustaining and crowning at the same time for a fitting peroration. In fact I havenít heard the organ contribution in Mahlerís Second better than this. I enjoyed and admired Littonís recording of Mahlerís Second. I could have done with less a sense of "containment" for Mahlerís most audacious conception, especially in the first and third movements, more feeling of a "live" performance. The liner notes tell us that this is "live" but four different dates are given so I presume four different performances were edited together to make up one to issue. I would suggest to Delos this is stretching the definition of "live" beyond breaking point even to the extent that what we have actually a studio recording in all but name. At no time was I aware of an audience present, or of an orchestra showing signs of stress, or of a conductor taking chances. Certainly not that ineffable "something" that "live" performing brings. Perhaps the idea of recording like this was to take away all the vices of "live" recording. The problem, for me, is that virtues are missing too. In which case why not just record it under studio conditions and leave it at that? Maybe one "live" performance "warts and all" would have given us that sense of "all or nothing" the work benefits from: the kind of numbing experience it can certainly give, even on record, and which Iím sure Litton and his excellent orchestra is capable of. As I have indicated it has always seemed to me that performances of Mahlerís Second Symphony fall broadly into two types, best illustrated by the recordings of Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer. Walterís lyric tone stressing spirituality and faith, the certainties that run beneath this work and which win out in the end. Klemperer's more austere sound palette, his leaning towards more ironic elements, his willingness to press on when others pull back (apart from his perverse, though quite unforgettable, delivery of the march in the last movement) suggests the uncertainties that run beneath the music, in spite of which we win through to the same conclusion. Most conductors approaching this work fall broadly into the former category but I feel Klempererís way with the music is ultimately more satisfying. Where the Walter approach takes Mahler's apparent certainty of deliverance at face value Klemperer asks questions of it and so makes the work even more involving and ultimately more moving in being concerned as much with what we leave behind as with what we might inherit in a world to come, and that way can the magnitude of our hard-won salvation be best gauged.

However, for me, on the downside there is the way the brass seem to be reined back at crucial moments, either by Chailly, by the recorded sound, or both. For example what should be the truly terrifying moment of recapitulation in the first movement emerges as little more than a few shakes of the fist when compared to Rattle or Bernstein who shake the living daylights out of us. The march of the dead in the last movement, while certainly not rushed as it sometimes is, even at this steadier tempo misses the truculence and the consequent inexorable cranking up of tension that you get with Klemperer and Rattle. I also think Chailly crucially takes just too long ushering in the start of the last movement after the glorious "Urlicht". There are crucial seconds of pause between the movements that really spoil the inner dynamic of what Mahler is doing. The great final tableau should burst in on us immediately, sweep away what has just calmed and consoled us. Here it is as if Chailly wants to make sure we are all prepared and ready for the outburst which, when it comes, therefore doesnít have the sense of a crack in doom opening up before us. Was this his decision or that of his producer? Later the two great percussion crescendi at 191-193 are somewhat truncated, although Chailly is certainly not alone in that. The final pages are handled superbly by Riccardo Chailly, however, with the fine chorus singing their hearts out. I liked the deep bells Chailly employs too, though I wish they could have been closer balanced along with the organ which fails to make the heart-stopping effect that it can. The Decca recording is rich and spacious. Maybe too spacious at times. There are some crucial timpani solos that really are rather distant and detached and fail to shock. On balance I do think that the way the brass is balanced backward has a lot to do with the fact that when they are supposed to knock us over they donít. The Concertgebouw hall is famed for its acoustic and I have heard "live" recordings made in it that exploits this to the full and leaves an unforgettable impression. But that is with an audience present who soak up some of the reverberation that here does occasionally show signs of blurring our, and possibly Chaillyís, focus. The orchestra plays superbly throughout with all their experience in this composer coming out effortlessly. Perhaps they play too effortlessly for those of us who prefer to hear some evidence of struggle going on in a Mahler work where striving against forces pitched against us are an important part of the mix. The inclusion in this Chailly release of "Todtenfeier", the original version of what became the first movement of this symphony, is apt but surprising. If you are interested in Mahlerís first thoughts at a time when he only had in mind writing this single, standalone piece then Chailly is as good as any version you can find. However, I doubt anyone will be buying these discs just to get this piece. It is clear from the expanded orchestration and the excision of certain passages that the later version is superior and that Mahler knew exactly what he was doing in revising it and absorbing it into the work that was subconsciously bubbling in his head all the time. Inclusion of the Litton and Chailly recordings are, I think, enough in this survey to appeal most to those looking for top notch playing and modern sound allied to fine interpretation whilst not quite challenging those recordings that I consider to be the crème de la crème even in spite of less opulent sound and playing - part of the philosophy behind this survey. This means that I have decided not to include among main recommendations the recordings by Yoel Levi and the Atlanta Symphony on Telarc (2CD80548) and Leonard Slatkin and the St Louis Symphony also on Telarc (B000A0GOLO). To do so would be to include recordings just for the sake of having them in and this series of surveys is not, as I explained in my Preface, intended to be exhaustive and all-inclusive. This also accounts for the fact that I have now decided to leave out the Berlin Philharmonic recording by Bernard Haitink on Philips (4389352) that I included in the first version of this survey. Haitinkís recording is now edged out by others. There are no other studio recordings that I feel the need to include at this time, which means that this is now the time to deal with "live" concert recordings. Can any of these be as great as Rattle's and Klemperer's and Walterís in their different ways and also benefit further from the "live" element? A "live" recording by Bruno Walter with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1948 has been available on and off for many years and certainly should be considered by those who value "live" recordings of historic stature of which this certainly is. It resurfaced most recently in an issue from Andante coupled with a "live" Mahler Fourth and Das Lied Von Der Erde, all recorded in Vienna. But beware of this set. In the first movement of the Second Symphony the final note is missing, the recording seems to cut off just before them. In such an expensive issue this is both surprising and unacceptable. If you want to find this recording look out for the Japanese CBS/Sony issue (42DC5197-8) where all the notes are present. I wouldnít place this ahead of the New York stereo recording by Walter - the mono sound and the "live" playing are inferior - but in terms of atmosphere and Mahlerian feeling it still packs a punch. Another not to be missed "live" performance is by Leopold Stokowski at the 1963 Proms in Londonís Royal Albert Hall. This too has been around some time on a pirate release but now BBC Legends (BBCL 4136-2) has it out officially at last in "bassy", though largely undistorted, mono sound that doesnít deliver much in the way of dynamic range, though I found more than enough atmosphere to convey the magic of what must have been a real night to remember. This was both Stokowskiís and the Mahler Secondís first appearance at a Proms concert and both rise to the occasion. Stokowski provides a superb sense of "line" from first note to last. His first movement is big and dramatic and incident packed. He does play fast and loose with a lot of Mahlerís markings - the climax of the development especially - but such is the conviction with which he does it all that the sense of portent and occasion that is conveyed sweeps all before it. The fifth movement is as apocalyptic as you could wish for, though it must be said that the off-stage effects are too close and the choral entry seems to get caught up with the birdsong and fanfares where Mahler specifically asks for a pause. The final hymn is both grand and intense though I could have done without the tam-tam crescendo at the very end - a Stokowski "changement" that had to be expected somewhere. The young Janet Baker gives notice of what is still to come from her in this work for Barbirolli, Bernstein and Rattle, but Rae Woodland is only adequate as the soprano. A big chorus sings lustily and fills the acoustically untreated 1963 Albert Hall to round off a night that really needed to have been experienced in person, especially the legendary encore which consisted of the close of the work all over again! Seek it out for that proof that this work, above all of Mahlerís, needs the concert hall and you will not be disappointed if you can "tolerate" mono sound. Had this been recorded a few years later in good stereo then I would certainly have included it as one of my main recommendations. There is another Mahler Second on the BBC Legends label by the Munich Philharmonic conducted by Rudolf Kempe (BBCL 41292 ) and you may see it advertised. In case anyone might think that anything "live" from this label will find favour with me, let me disavow them. It was recorded at the one and only short Winter Proms season that the BBC mounted in 1972 and was given on a late Sunday afternoon. As I recall, the orchestraís flight was delayed and so their preparation for the Royal Albert Hall was limited. Kempe did not seem in sympathy with the work either and so my advice is to pass it by. We certainly could do with a good stereo performance of the Second from the Proms in London. Rattle and the Vienna Philharmonic gave one a few years ago and that was superb. How about it, BBC Legends? Six years later in 1969 the Proms in London heard its second Mahler Second. This time the conductor was Bernard Haitink and one listener at home that night listening on the radio was the present author hearing a Mahler symphony for the very first time. Then five years after that came the third performance at the Proms of the Second. This time the conductor was Pierre Boulez in a concert to mark the retirement of the BBCís then Controller of Music Sir William Glock. (In the first half Glock played piano is a chamber recital.) The recording of the Mahler is on the hard-to-find Originals label (SH 855/6) but it is worth seeking out for another one-off, "live" experience of this work by a conductor then not usually associated with it. A drawback on this issue is the recorded sound. This is an unofficial "air check" and betrays this in fuzziness in frequencies around the carrier. Beyond that, the stereo sound is typical of the kind the BBC were getting pre-digital at the Royal Albert Hall: a bit bass heavy and a bit treble clipped like the Stokowski. In addition the engineers have to mount some damage control in the big moments. No distortion, just a reigning back in volume so everything is contained. There is a nice impression of the hall which Boulez uses to the full in the directional moments: the off-stage band, the fanfares and the soloists. I have heard a better recording of this from a private collection so I donít give up hope that the BBC might even still possess the master tape and consider a release. (Though with DG poised to issue a new studio version under Boulez with the Vienna Philharmonic during 2006 I will not hold my breath.) The opening is very grim, but also grand with a tremendous first challenge where every note is carefully articulated. Not for Boulez the mad rush of notes we too often hear. Then, in the wondrous second subject, he moulds and caresses the theme with real old-world charm and the pastoral interlude too is given all the time it needs. I like the way Boulez makes woodwind solos leap out and shriek from the texture and each time he does so I'm reminded of the Seventh Symphony's scherzo. The drive towards the crisis before the Recapitulation, those great dead chords crashed out by brass and percussion, is taken steadily with the effect of a great threshing machine heading for us. The second movement receives a conventional reading, though I like the way Boulez encourages the cellos to really sing and also for the prominence given to the harp - though that might have been a trick of the recording balance. Boulez's tempo for the third movement is quicker overall, accentuating bitterness and irony. Again he makes the woodwind really leap out, but there's no relaxation at all for the marvellous trumpet solo. In the fourth movement Tatiana Troyanos's "Urlicht" puts me in mind of Erda in Wagner's Ring. In fact this was the era of Boulez's Bayreuth Ring, so that may not be too far from the truth. She really leans on the notes from above, making quite a mesmerising sound. Not a comfortable sound, though. Then Boulez crowns the performance with a stunning realisation of the last movement. He goes for drama and spectacle, even seeming to glory in the huge contrasts and the directional moments. In the first off-stage horn calls Boulez's use of the acoustic properties of the Royal Albert Hall is evident. In fact if you listen very carefully here you can just hear the London traffic outside. In those early pages of woodwind and brass fanfares Boulez seems to luxuriate in the different sounds all the combinations produce, with the omnipresent off stage horn acting like a kind of sentinel at the gates of doom. The first "Oh glaube" is full of mystery and foreboding but that changes to desperation as the woodwind join in, screeching in protest. Then there's a huge pause before the great brass chorale brings that wonderful outburst of exultant fanfares before the percussion crescendi. I like Boulez's tempo for the march. He seems to agree too quick a speed is fundamentally wrong here. He isn't as slow as Klemperer, but he's not far off and the gain in weight is considerable. This tempo seems to put new fire in the BBC Symphony's collective belly and the performance by now has taken on a new life. At the collapse of the march Boulez takes care to ensure every detail is heard and even in the rather diffuse recording details tell. Then there's a very deliberate return of the "Oh glaube" material with the off-stage band really distant, way up in the gallery, I would imagine, accentuating again the use by Boulez of the acoustic space the Royal Albert Hall offers. The crisis before the Grosse Appell caps the previous one as it should and we are ready for glory. In another telling use of space Boulez positions his brass for the Grosse Appell closer so, at the moment the whole lot pile in over the flutes, the effect is thrilling. After the choir alone, the entry of orchestra brings a great feeling of ecstasy but there were moments when I was reminded of the opening of Schoenberg's Gurrelieder, which was not many years away when Mahler wrote this symphony. The ending of the work never fails. Just to say the chorus is wonderfully together and the organ really tells. I get the impression this is one of those "sense of occasion" performances and the roar of the audience at the end, unfortunately clipped after a few seconds. Hi-fi enthusiasts will turn up their noses at this but Mahler enthusiasts should give it serious consideration if they can get it as an alternative to any main version. When DG do release their new recording it will be fascinating to hear Boulezís present thoughts on this work and whether the improved sound we will undoubtedly hear adds up to an issue to supplant the "live" one. Appropriately in the last months of his life Sir John Barbirolli was much concerned with Mahler's Second. He performed it in both Manchester and Stuttgart and the latter performance was taped for broadcast. "It was as if the great old man was trying to shake the gates of eternity from their hinges," wrote a member of the audience in Stuttgart on 5 April 1970 to the Intendant of the Berlin Philharmonic. Fortunately an unofficial "aircheck" has been available for some years and I featured it in the first version of this survey. Sound-wise it had considerable limitations and was hard to find. However it was always known that Stuttgart Radio retained the master tape and many of us who admired the performance hoped one day it would get an official release. That day came with the recording forming the centrepiece of a set in EMI's "Great Conductors of the 20th Century" series (5 75100 2) and can now be included here.

It really takes a master conductor of Mahler to recognise and bring out the ironies and sarcasm in the third movement and Barbirolli is certainly in that category on this evidence alone. He does it by seeming to have grasped that this is firstly very weird and unhinged music indeed. Mahler after all wrote of seeing the world in a concave mirror. Those prominent wind lines I mentioned earlier are used again to full effect to convey this. The constant hinting of an uneasy lyricism at the heart of this movement shows Barbirolli recognises that this is very uncomfortable music too. I also like the col legno snaps from the strings as well. They suggest the sharp edges of the movement so fittingly. The central section strives and exhilarates but the trumpet solo at the heart is delivered like no other performance I know, not even Klemperer's, so full is it of aching nostalgia among the kaleidoscope. Exactly as it should be. Why can't other conductors get their solo trumpeters to play it like this? Are the players too afraid of sounding cheap? Note again the lovely pointing of the woodwind, perky and cheeky, and then the rush to the cry of disgust where a sharp and grand quality then enters the music delivering weight and true power. In the fourth movement Birgit Finnilä is suitably dark in "Urlicht" but notice the deliberate pointing of the brass against her opening line and then the final flourish on the strings as the movement closes. This is a unique touch of JB in the night, I think. A bit naughty, but I would be happy to enter his plea in mitigation after a visit from the score police. All in all this is a very Mahlerian reading of the movement. By that I mean that it's full of delicious "Wunderhorn" characteristics - note the plangent brass and the melodic line stressed. Not the rather pious, prissy hymn we too often hear. The fifth movement then bursts in with fine abandon and notice the prominence given to the fine woodwind players again as the music settles down. After the off-stage "voice in wilderness" the approach by Barbirolli as the ascent begins is remarkably direct, no hamming, no mannerism. The Music is allowed to speak for itself but with some fine highlighting of solo instruments to vary the texture and keep the ear always interested. Barbirolli recognises the drama within the music superbly and that it must be varied. There is even a lilt in the way the music gathers strength and still he doesn't linger as some conductors do seeming to have a much tougher conception, and so it will prove as time goes on. The first appearance of the "O Glaube" motive becomes superbly restless, a small cauldron bubbling away and then the solemn brass with very fruity vibrato leads to a fine climax which caps the episode with drama and colour. The great march is again Klemperer-like, this time in its sheer guts and trenchancy. It is also very colourful and not a little manic. There are some fluffs from the brass in the cut and thrust of this "live" performance, but what do you expect? Anyway these only add to the experience of struggle and travail. You can hear everything clearly also because, like all the great Mahler conductors, Barbirolli knew to make every note count, especially in the crises that engulf at the march's end. These are remarkable for their clarity, as also is the interlude with the off-stage brass band that contains a truly snarling trombone solo and great swagger from the band. One of the best realisations of this crucial moment I have heard. When the chorus enters there is real serenity. Not the serenity of a plaster saint but of a man who has seen life, sinned and repented before a hard-won deliverance that rises at the end to triumphant, dramatic paean. If you know Barbirolli's studio recordings of Mahler this may not be the kind of performance you would expect. It's a fascinating reading full of insight, drama and a sense of danger. Both from the fact that it's "live" and also from Sir John's own philosophy of Mahler in performance with the score as almost a living entity that should come off the page. Rather like his performance of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony from six weeks later in London he also seems to expose the nerve ends of the music and rage against the creeping shadow of his own mortality to a degree that is, in hindsight, deeply moving. Shaking the gates of eternity, as that member of audience in Stuttgart so perceptively noted. Such a distinctive reading demands consideration both in itself and as evidence of one of the great Mahlerians caught "on the wing" and in the final weeks of his life. It is flawed in execution, though. As I have said, there are a few fluffs in the ensemble, most times in places that you wouldn't expect any problems to occur. Apart from the passage in the first movement recapitulation already mentioned the worst moment is probably when the whole trumpet section misses its climactic entry in the coda of the last movement and comes in a bar or two late. Nothing can be done about this but to throw out this recording on the back of explainable and excusable lapses such as this would be perverse in the extreme. Like dismissing an Olivier or a Wolfit in "King Lear" just because of a missed line or cue. I also believe that, in spite that, this is a performance touched with genius. Not a recording for the everyday, certainly. One to take down every so often with the virtues surely outweighing the vices. The sound on this official issue is now a profound improvement on the old "aircheck" featured in this survey first time around. Not "top flight" sound when compared with new recordings, but a good stereo picture with no distortion, clear lines and a sense of space. At the time of writing the first version of this survey there was also an unofficial release available of Barbirolli conducting the Second Symphony in Berlin with the Philharmonic in June 1965. Since then this too has been officially released on Testament (SBT2 1320). The Berlin Philharmonic show signs of being a better orchestra than the Stuttgart Radio Orchestra, as you would expect. But their grasp of the music seems less sure. They didnít play much Mahler at that time and it is as if Barbirolli had had to teach them what Mahler should sound like, so bringing an element of the "run through" about it when compared with the Stuttgart concert. The sound from Berlin is also in mono and a touch limited in the treble. But for Barbirolli admirers it is certainly one to consider, especially with Janet Baker as contralto soloist. Michael Gielenís Baden-Baden recordings of Mahler are notable for their clarity of execution and eschewing of romantic baggage. In this heís an interpreter who sees Mahler very much precursor of radical pioneers of twentieth century music who so admired him rather than inheritor of the nineteenth century symphonic tradition which these men ultimately rebelled against. A valid and valuable view which, in the case of works like the Seventh and Ninth symphonies where Mahlerís forward looking aspect is more clearly apparent, presents us with results that provide a necessary strand of interpretation if we are to come to terms with these particular works. However we are on more controversial ground when this approach is applied to earlier works like the Second Symphony on Hänssler (HAN93001). Here the long shadow of late Nineteenth century Romanticism, both in the writing and philosophical well-spring, surely demands greater personal involvement on the part of the conductor, a more expressive style and even a dash of the virtuoso showman. The religious text affirming faith in the Christian resurrection that forms the centrepiece of the work especially calls for a theatrical style of some kind otherwise the alienation of the listener from Mahlerís central message cannot be ruled out. As we have seen only Klemperer really delivers something radically different and I believe is even more rewarding. But any lack of orthodox expressive style in Klempererís interpretation is made up for by a keen sense of drama and an almost truculent insistence on wearing the "hair shirt" of the man who asks questions of a work others are prepared to take at face value. Klemperer was a deeply religious man for all his apparent scepticism. The fact he asked questions of what is a fundamentally religious statement only seems to add depth and power to his view of it because you somehow know that his doubts hurt him deeply. Michael Gielen plays the sceptic too but he doesnít interrogate the music in the way Klemperer does and so thereís a small loss in drama, involvement, and that rare aspect of music making to really pin down, empathy, to be encountered and dealt with by anyone coming to this recording. Gielen is rather like an investigator who has been asked to deliver a detailed report on a tragedy after it has taken place, rather than be the conduit through which we see the chain of events enacted before us. A little like the Chorus in Greek Tragedy who comes onstage to describe the slaughter that has taken place behind the scenes for us to then use our own imaginations to fill out. So there is a crucial element of alienation at work in Gielenís recording of Mahlerís Second, a feeling of taking a step or two back from the fray. Whether, as with the Chorus in Greek Tragedy, this becomes a creative aspect that throws light on the fundamentals of this symphony can only be decided on by the listener. In the first movement listen to the ascending strings at the start of the first development (bars 117-128). Others invest this passage with aching nostalgia whereas Gielen wants to stress cool detachment. Then in the second movement, at bars 39-85, marked "Donít hurry", hear how Gielen stresses head over heart once again in the celloís counter melody which is precise and unbending in opposition to most conductorsí view including, so we gather from contemporary accounts, Mahlerís own. In the last movement I donít think I have ever heard the early choral passages taken quite so flowingly, or so forwardly projected, as they are here. Almost as if Gielen is ashamed of any sense of poetry and mysticism Mahler may have intended. Itís certainly different from what we are used to, though I found it most arresting, which surprised me. In the closing pages thereís a sharpness of focus also, as is the case right through. At every turn Gielen is low on spirituality, high on clarity. I would certainly rather possess this reading of the Mahler Second than not, but itís one I donít think I will listen to all that often. The playing is distinguished and suits the "hands-off" approach of its conductor and the recording has a good sense of concert hall for what is a "live" performance. For consistency of vision and for delivering his very modernist and individual view of Maherís Second Gielen has to be congratulated, even though this may not be most peopleís idea of how this work should be played. Ultimately itís just too cool and detached to endear itself but if you are looking for an alternative to the more conventional conductor-involved ones, Gielen is your man.