1 Jazz Me Blues

Mckenzie & Condon's Chicagoans:

2 Sugar

3 China Boy

4 Nobody's Sweetheart

5 Liza

The Chicago Rhythm Kings:

6 There'll Be Some Changes Made

7 I've Found A New Baby

8 Baby, Won't You Please Come Home?

9 Friars' Point Shuffle

10 The Darktown Strutters' Ball

Charles Pierce & His Orchestra:

11 Bullfrog Blues

12 I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate

13 Nobody's Sweetheart

Miff Mole & His Molers:

14 One Step To Heaven (Windy City Stomp)

15 Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble

Eddie Condon & His Quartet:

16 Oh, Baby!

17 Indiana

The Dorsey Brothers & Their Orchestra:

18 'Round Evening

The Big Aces:

19 Cherry

Wingy Manone & His Club Royale Orchestra:

20 Trying To Stop My Crying

21 Isn't There A Little Love?

Ted Lewis & His Band:

22 Wabash Blues

Elmer Schoebel & His Friars Society Orchestra:

23 Copenhagen

24 Prince Of Wails

The Cellar Boys:

25 Barrelhouse Stomp

26 Wailing Blues

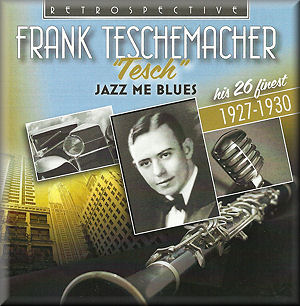

Frank Teschemacher & His Chicagoans

Frank Teschemacher (1906-1932) was a grievous casualty, an astonishing

individualist, and a cranky stylist, who died in a car crash before

he was 26. His hero was Bix Beiderbecke, who had only recently predeceased

the Kansas City native, and Tesch's principal beneficiary, in one

sense, was the equally ruggedly individualistic Pee Wee Russell, though

his influence on Benny Goodman is also strong and acknowledged.

Obviously, there's a `catch him while you can' quality to his recorded

life. It starts in this Retrospective single disc back in 1928 with

the track that gives the album its title, Jazz Me Blues,

and gives us a template for white Chicago jazz, albeit with a two

man front line of alto and clarinet, which was a clear reference to

what Jimmy Noone and Doc Poston were doing on the (black) South Side

of the city. I should add that Mezz Mezzrow was also on clarinet,

but fortunately we don't hear much of him. It's actually quite a hesitant

number and I don't rate it highly, even if the alto was the fine Rod

Cless.

There then follow four total classics, recorded the previous year,

and played by McKenzie and Condon's Chicagoans, that all lovers of

such things will know by heart. How amazing for me to remember that

one of the musicians in that band, Jimmy McPartland, once put his

big paw on my shoulder at the 100 Club in London and said to me, kindly,

as he passed; `Scuse me, son'. He then sat on the chair Bix had used

back in Whiteman days and blew the place down.

One should always note the sheer angularity of Tesch's playing,

its Cubist lines to the fore, and the hot company he kept - all the

very best of his confreres, which meant Muggsy Spanier, Joe Sullivan,

Eddie Condon, Red Nichols and Gene Krupa and all the gang. There's

a modern sounding riff on Bullfrog Blues where Tesch's clarinet

edges towards Johnny Dodds, himself active in the city at the time.

Not everything works, despite the tight company. The Dorsey Brothers

band and The Big Aces are both disappointing, the latter especially

as it included Jack Teagarden and Don Redman, but the results are

souped up dance band music. Ted Lewis's ghastly Wabash Blues

is still puke-making. Also Dick Feige was no Spanier and not all the

Charles Pierce tracks are especially good. Indeed Miff Mole's band

rather sweeps them away, both musically and in terms of recording

quality - hardly a fair comparison, of course, as Mole was an elite

player and his companions included Nichols, Sullivan, Condon and Krupa.

And more kudos comes via The Cellar Boys, where Wingy Manone blows

a superb cornet, Charles Melrose plays a mean accordion, and tenor

player Bud Freeman proves that he was ahead of the game back in 1930.

So, some rather up and down sessions here. But that's what happens

when your recording career lasts barely two and a bit years. Inevitably

there will be dullish or eccentric sessions to be balanced by some

of the hottest, most driving Chicagoan jazz this side of Heaven.

Transfers are good. The personnel listings are generally accurate

but I noted a few misattributions and mistakes.

Jonathan Woolf

See also review by Tony

Augarde