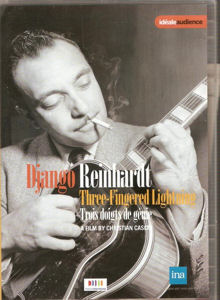

A film by Christian Cascio

TV Format: NTSC 16:9; Sound PCM Stereo: Languages: GB, D, F, E,

Region Code: 0

[66:00]

It's a curiosity that one of the most extensive pieces of footage of Django Reinhardt comes not via Paris but in a BBC film of the Quintet of the Hot Club of France, recorded in London in 1938. It's included as an appendix, along with three performances played by his guitarist grandson David Reinhardt, though a taste is given in Christian Cascio's 52 minute documentary film, and shows the group relaxing by playing cards through a haze of cigarette smoke, or sitting about practising. The footage is dim at first and one can't see Django's face at all, or very much, when he first solos - after the boys stop acting for the camera and join him - but thereafter the focus is sharper and the print improves. It shows us everything admirable in the group; superb swing, intricate melodic distribution between Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli, the dependability of the two-man guitar team behind Reinhardt, and the oak-like strength of the role of the bass in the quintet.

I don't recall ever having seen much footage of Reinhardt; plenty of Grappelli, of course, but his front-line partner was an evasive soul, physically, psychically, and ever on the move, like his Gypsy brothers and sisters. When he wanted to rest, he rested. If he'd lived beyond the miserly 43 years accorded him, we would doubtless have had more. Would he have recorded with Sidney Bechet? He certainly made music with pianist Martial Solal, from whom we hear, drawing our attention to the miracle of the guitarist's phrase endings, but who confesses he was very nervous and uncomfortable recording with the older man.

This documentary was made for French TV. It's narrated by IrŐne Jacob, the actress, in English. Some of the spoken text is, to these prosaic English ears, somewhat hysterical and poetic in the French manner, more Baudelaire than biography. Still, if you can stomach this Gallic excess, there is much to enjoy. There is a lot of footage of Paris in the 30s, evocative material from which milieu the itinerant Reinhardt most certainly did not emerge but in which milieu he swam playing in musette orchestras. It's sometimes forgotten that he made his first recordings in an accordion band in 1928 when he was 18. This was before the catastrophic caravan fire that cost him the partial use of his left hand, rendering his fingers petrified and scarred.

We follow the guitarist as his steps a gear up via crooner Jean Sablon, and the evenings spent with his staple repertoire of the time; waltzes, tangos and the like. His colleagues in the budding Quintet would have played jazz, but only during intermissions, when hair could be let down a bit. Thus did the QHCF find itself.

We hear from Grappelli in black and white and also colour interviews, down the years. The venerable writer and critic André Hodier is also interviewed, reminding me of guitarist Eddie Condon's reaction to French critic Hugues Panassié writing a book on Jazz and arriving in New York to superintend recording sessions with local musicians: 'Who does he think he is; I don't go to France and tell him how to jump on a grape'. There's also an engaging black and white interview with Henri Salvador who knew and worked alongside Reinhardt and speaks pithily about him.

It's also interesting to remember that the Quintet was, for whatever reasons, actually more popular during 1941-43 than they ever were before the war in what we now think of as their heyday. Maybe it was the war, but the loss of Grappelli - because of the war the violinist stayed in London and teamed up with George Shearing and others - certainly didn't dim their popularity at all. Reinhardt continued with clarinettist Hubert Rostaing and a drummer. I've always liked this band but never loved it.

One of the most important things in this documentary is the chance to hear Reinhardt talk. His speaking voice is slow, low and measured. He can be uncommunicative and monosyllabic unless scripted or truly engaged in the conversation. He talks too about his Mass, which obsessed him. He could be capricious, making demands so unreasonable that The Rolling Stones would blanch. Toward the end of his life he discovered painting and like many a jazz musician - think of Pee Wee Russell for example - he launched into what was almost a second career, emotionally if not in actuality.

One also discerns the trajectory of his music-making - remember he composed quite a bit - from musette, to tango, to his brand of swing, to bebop, even to a form of post-bop. We also hear from Babik Reinhardt, his son, in a radio interview; also rather taciturn. The unsatisfactory tour with Ellington in America isn't glossed over.

And there is footage, very moving, of Reinhardt's funeral. Felled by a stroke at 43, the most inspiring of all European jazz musicians left as abruptly as was his custom.

Jonathan Woolf