Peter Crossley-Holland was an influential young man in the musical world who had been asked by Max Hinrichsen to write a four-page article (see Appendix) about me and my music at the time of The Partisans. He included my three operas, the Three Chinese Pictures, Five Bells, Heyday Freedom, and the Overture Per Mare Per Terram. It was a very searching and flattering article that treated me as a promising young composer of distinction and should have done much to assist my fortunes, but how far it was distributed I do not know. I have a large number of copies here today which, one would have thought, would have been better distributed at the time When I first met Peter Crossley-Holland, he seemed a rather quiet personality, but I soon found that the Celtic element in my name was like an "open sesame." In the past I had tended to discount everything that belonged to my Father’s side, because the music clearly came from my Mother and Grandmother, but now I was beginning to see that the Cornish element was destined to have considerable influence. And this was considerably due to my friendship with Peter Crossley-Holland. But for the moment it was an Elizabethan subject to which I was drawn. Perhaps it was a conscious attempt to get away from modernism of The Partisans. I studied the Elizabethan style in the music of the time and found there was a distinct idiom in the music of the period to which I frequently had recourse in writing my Avon.

The composition of this opera inspired a sonnet in which Peter Crossley-Holland took great interest and though he did not write it, he helped in its final formation:

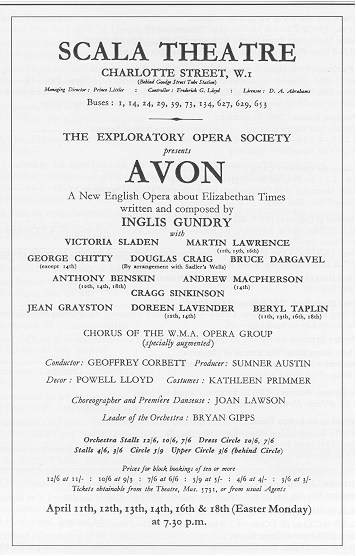

Production photos of AVON here The story of the opera is based on that of John Wilbye, the Household Musician of Hengrave Hall in Suffolk, who was believed to be in love with his patroness, Lady Rivers. This is thought to have been the reason for the vivid expression of the words for some of his madrigals which were dedicated to her, though of course it was the fashion of the time to use extravagant language. My John Hailey, the Household Musician at Avon Feldon is definitely in love with Lady Laura, daughter of the Countess of Avon Feldon. Sadly for Hailey and for Lady Laura a marriage has been arranged between Lady Laura and Lord Buckridge, a typical hunting squire, "who has no music in his soul" but is the master of Arden, which is on the other side of the Avon. The Countess sees this as a wonderful way of uniting Arden and Feldon, separated only by the waters of the river Avon. Lady Laura who is an admirer of John Hailey is not at all in love with Lord Buckridge, but feels it her duty to comply with her Mother’s wishes. To add to poor Hailey’s predicament, an irritating rival musician arrives at the Hall, who claims to have all the latest dodges up his sleeve. Hoperario, whose real name is Hooper, and Sir Timothy, the steward at the Hall, sees this as a marvellous after dinner entertainment - a contest between the rival musicians. Hailey, as the reigning household musician, is to sing first, and then Hoperario. Hailey sings a love-song addressed with little disguise to his beloved Lady Laura which only she, however, can recognise. Then it is Hoperario’s turn. He sees in the Long Gallery where they are meeting a tapestry portraying the story of Diana and Actaeon. The assembled people move round to face the tapestry, which seems to come to life as a light shines behind the gauze and dancers portray the story of Diana and Actaeon as Hoperario relates it. Such is the excitement engendered by this unusual procedure that it seems easily to have won the laurels over a simple love-song. Hoperario is declared the winner and everyone retires for the dance leaving Hailey and Lady Laura alone on the stage. He wants to say good-bye to her, for he has decided to leave. "What will you do?" she enquires anxiously as the music of the pavane starts up behind scenes. "I don’t know", he replies. "I expect I can earn enough to keep myself as an itinerant musician in London" The pavane leads into the galliard. Servants keep arriving from the ballroom to require the presence of Lady Laura. She stays saying a last farewell to John Hailey until at last she feels she must go. The Second Act, which is in London, is in strong contrast to the First, which took place in the country on the banks of the Avon. Shakespeare’s prophecy "The man that hath no music in his soul. Is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils" is being carried out, for it is the day of the Essex Rebellion and Lord Buckridge is involved as one of the conspirators. Strange that Britten chose this same conspiracy for his Gloriana which was performed some time later than this occasion. I certainly claim precedence on this occasion. The Elizabethans have left us two works in which their street-cries are paraded one after another. This is not likely to have been their sequence in real life. I have ventured to put them together. Thus while the orange-girls sing their beautiful "Fine civil oranges;" some men are offering their "dish of eels" and while other girls offer their "white lettuce, white young lettuce" a cooper begins his song; "A cooper I am and have been long …" Apparently the main shopping area was the streets, which must have been loud with clashing song. However there comes a lull and we catch a glimpse of Hailey, now a street musician. He has managed to throw off, at any rate temporarily his passion for Lady Laura, but would be glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. We see him go towards the Black Wolf Tavern with his: "Will ye have any music, gentlemen?" But the door is slammed in his face. Apparently he has chosen one of the pubs where the conspirators are gathering and soon it becomes clear that these conspirators happen to be Lord Buckridge with Sir Timothy and Hoperario. There seems some doubt as to where the conspirators are supposed to be rallying - the Court, the City or the Tower. Buckridge decides to make for the Court, where he knows his wife is. When the curtain rises on the Second Scene, we are in the Court, Lady Laura and the Countess are standing near the windows listening to the Conspirators who are outside in the streets proclaiming their conspiracy. When they have gone Laura returns to her virginals on the table (She is playing Lady Carey’s Dump) and the Countess to her chair. The Countess continues singing about Buckridge. He is not perhaps all that they had hoped but he is still young and there is hope he may improve. She thinks he has not joined the conspiracy. When Laura joins in she is in despair. Perhaps she knows more than her Mother. The Countess goes and Buckridge appears from a different door. He tries to enlist his wife in the conspiracy, but Laura is adamant "I will not lift a finger against the Queen." The Countess reappears with the news that the Conspirators have gone to the City. Seeing Buckridge she approaches him. "I am glad you are here," then leaves husband and wife alone together. Buckridge tries further to enlist his wife in the conspiracy,

But Laura cannot agree to this. It becomes clear that over this sort of issue there is real unbridgeable enmity between them. He turns on her in a fury. "You have never loved me. You have never been able to give me the true fearless love I craved." He seizes her roughly. "And now go back to your dumps, your fadings, your psalm-singing madrigals but do not stand in my way." He strikes her and pushes her away. "And now go tell the Queen that I am a traitor. Inform against me, and damn yourself." He storms out, leaving her sobbing on the floor, In the third scene we find the street-singers and the Conspirators ranged against each other. Hailey and Benson a poet and actor from one of the theatres find themselves the champions of the people while Sir Timothy and Hoperario try to win over the people by chanting the conspiratorial songs of the time:

But the Conspirators failed to impress the people on behalf of the Earl of Essex. The Third Act starts with the usual orchestral introduction, in which the imitation of the wood-pigeon’s song proclaims that we are back in the country. Sir Timothy and Hoperario are trying to cover up their involvement in the conspiracy by staging a Welcome Ode to Laura and the Countess who are expected to be returning to Avon Feldon at any moment. But Mrs. Willoughby, the House-keeper, is not a good choice for "Stop, stranger" which is the opening of the Masque. She will get things wrong and there is obvious friction between the elaborate arrangements Hoperario has made for the music and the positioning of the bodies of the servants. A false alarm is caused by the arrival of Hailey and Benson singing as they come down the drive "Hailey! The very man!" calls out Sir Timothy, to the disgust of Hoperario, who retires into the Hall. "A Welcome Ode for Lady Laura and the Countess." "If you want a real actor, here is one," says Hailey, pointing to Benson. Mrs. Willoughby is only too pleased to hand over her part, which Benson looks at and quickly knows by heart. Soon the Countess and Laura are seen approaching, announced by trumpets in the drive. "Stop strangers," commands Benson. At the end of the Masque, the Countess thanks her servants warmly for their welcome and proceeds into the house. Laura, much moved, adds her appreciation. "There was a singer once …" Sir Timothy takes up the cue: "What singer, Madam? Is it John Hailey whom you mean? Our goddess here can summon him, wherever he may be. Avona fair," he calls to Mary, the high soprano. "Avona fair" obliges and soon John Hailey is seen emerging from the topiary. The others withdraw tactfully, leaving Lady Laura and John Hailey together. Hailey tries to calm Laura with the music of Avon, but she is haunted by fear of her husband’s return. A Sergeant arrives with armed men. He has a warrant for the arrest of Lord Buckridge. But is led to search the house. Meanwhile Buckridge himself arrives and is warned to take refuges in the maze. But the Sergeant and his men re-enter from the house and proceed to search the maze. Buckridge is killed fighting his way out of the maze. Hailey again tries to comfort Laura, but we see that the social gulf between them cannot be bridged and Hailey must remain the ‘household musician’ in love with his Lady Laura, as John Wilbye may have been with his Lady Rivers. I tried hard to interest the musical powers-that-be in this opera, but without success. Max Hinrichsen provided a beautiful setting for a run-through, in which, I remember, I sang "Sir Timothy", but all the points seemed to pass unnoticed. I remember Professor Dent, who was usually quite partial to me, sitting back in an arm-chair, smiling at a cat which he was nursing. It was as if I was unable to make any impression with this opera. Or was it that the slur from The Partisans still hung over me? They perhaps suspected that it was all a piece of communist propaganda in disguise. Was I not still using the W.M.A. Singers? Nevertheless I was determined to give Avon the chance of a performance, With what money I could muster (much to my sister’s disgust) and with help from Vaughan Williams (which later he generously doubled). I engaged the old Scala Theatre for Holy Week 1949. My friends gathered round me, notably Pat Simpson who put her flat at my disposal. Antony Benskin, who took the part of Sir Timothy, stayed with her, whenever he was required in London and some of his pupils joined in, notably the high soprano, who sang the part of "Mary". Another friend, who gave me much support, was the artist, Kathleen Primmer, who designed some beautiful drawings and paintings for the scenery and costumes. I have her beautiful design for the gauze in Act I hanging on my wall to this day. She also arranged for the painting of the gauze which she did herself. Incidentally this gauze caused a great deal of trouble. First of all it was very difficult to find such a thing at all. When at last Kathleen Primmer had found one and I had paid for it, some different owners appeared on the scene claiming that the first owner had no right to sell it to us. At the end of the performances the costumes and scenery were packed up and delivered to the house where I live to this day, but when I came to look for the gauze sometime later, I found that it was not there. I can only conclude that the second owners managed to spirit it away from the theatre! The man I asked first to produce replied that the drama was impossible, but when I showed the same libretto to Harry Powell Lloyd, who also produced two of my later operas, he accepted and immediately did some designs for me. Unfortunately he was later offered a more lucrative job in South Africa and felt he had to take this opportunity, but I think it was through him that Sumner Austin became the eventual producer. My friend Geoffrey Corbett conducted a section of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the singers were first class. So we were able to put up a first class performance. But unfortunately the weather was against us. It happened to be a fine warm Easter when most people preferred to be in their garden, so after the first performance, when quite a few notabilities came, including Christie of Glyndebourne, audiences dropped away. Vaughan Williams and Ursula, who became the second Mrs. Vaughan Williams, came twice. Friends, like Sidney Harrison in John O’London’s Weekly, made much of it, but on the whole the Press was against it.

|