Douglas Lilburn, the New Zealand composer, was a great friend of mine from the Royal College of Music days and he stayed on in England after the War had started. He helped me considerably for my concert in early 1940 before he was recalled to New Zealand and I joined up.

All this time, as soon as I left the Royal College of Music I was writing my second opera, my first Three-Acter The Return of Odysseus. It must have been in 1939 or before that. Lawrence of Arabia published his translation of the "Odyssey" which made it clear that Homer’s "Odyssey" was possible subject for a libretto. Of course The Return of Ulysses had been often used as a libretto, by Monteverdi and others, but never before had anybody looked at the original Homer’s "Odyssey" as a possible subject for libretto-making, and yet what could be a better subject for an operatic aria than the following words which Penelope has as she descends from the women’s quarters to interrupt one of Phemius’ lays:

"Many other songs you know,

Songs that can enchant or soothe

Songs of heroes and of gods,

That poets love to celebrate.

Tell them one of these while they

Sit and drink their wine in silence.

Leave this bitter tale that always

Tears at my heart reminding me

Of that unforgettable sorrow

That crushes me above all women,

For I remember - ah! with how much longing

The dear head of my husband whose sad story

Rings in the voice of every poet and singer

Throughout the world."

What could be more suitable for an operatic aria? I was not so fortunate in the second scene, where Penelope is caught unravelling her day’s web by two of her suitors, but here I was able to make effective use of the musical device known as "cancrizans".

As I knew I was about to be called up, I thought it might be worth spending my all on a big last-minute jamboree before joining the Royal Navy. I did not know what might be my fate at sea with torpedoes rushing around, so I thought I would have a last fling before becoming a Jack Dusty as was to be my fate.

I hate now to think what it must have cost me. (Fortunately I can’t remember this) but I’m glad I did this, if only because it makes a good story for this book. As the Royal College of Music had been unwilling to spend money on my Naaman, I thought I would give my Return of Odysseus Act I, which was all that was written, the chance of a performance.

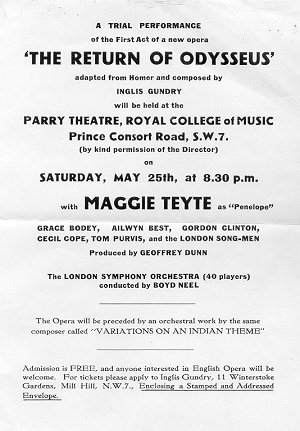

I booked the Parry Theatre for a certain evening in early 1940 and a section of the L.S.O. to be conducted by Boyd Neel. We had had a strict black-out all through the "phoney War" which I, as an air-raid warden had been engaged in enforcing. There were no concerts and no theatres. So this was an attempt to "beat the black-out" and perhaps it helped me to secure the services of people like Boyd Neel and Geoffrey Dunn, who was to produce. There were no costumes. It was just a walk-through in modern dress but it gave me an idea of the First Act of my opera, which was all that was completed at the time.

I assembled a distinguished number of singers, mainly from the Royal College of Music, Cecil Cope as Antinous, Tom Purvis as Eurymachus, Aylwyn Best as Telemachus, Gordon Clinton as Phemius, etc. For Penelope I thought I would go a splash and I managed to secure no less a person than Maggie Teyte at a reasonable stipend. The evening started with my Variations on an Indian Theme. I always remember V.W., who came to the rehearsal in the morning, asking if they could play over the theme of the Variations, which he had missed. It was a theme from Uday Shankar and his Dancers, which had fascinated me.

The Parry Theatre was thronged. Nobody had paid anything for their seat. Notices of the Concert had been distributed and left about in likely places like Augener’s showroom and Schott’s counter. It certainly succeeded in "beating the black-out" and it was noticeable that thereafter the concerts and theatres began again. I met a lady years after in one of my classes who said she had been there and had enjoyed it greatly. If only I had a recording, but of course it was before the days of amateur recording.

In all this my friend Douglas Lilburn was of great help. He gave out programmes for which there was no charge and showed people to their seats. It must have cost a bomb, and I’m sure my sister must have been most disapproving. I can’t remember that she ever came, but I felt it was all very much worthwhile for a young composer who was about to spend the next two years scattering mines and running the gauntlet to Malta. Act II and Act III of Return of Odysseus were to be written in moments of leave during the next two years, though it is true there were many vacant moments when it was possible to think things out, but only at home in peace and quiet was one able really to go ahead.

Act II is in two scenes. The first is in the Hall, and we find that Telemachus has borrowed a ship and gone on an expedition abroad. Antinous and the other Suitors are very worried about this, for they suspect that Telemachus has gone abroad to muster help against them. They resolve to lie in wait for him and cut him off before he can do them any mischief. The rest of the scene is taken up with a long lament for Penelope who has only just heard news of her son going abroad. She accuses her women of not keeping her informed, and Eurycleia, the old nurse, has to admit that Telemachus had made her swear that she would not tell Penelope about his travels, (a character very dear to me because I had been brought up with a Eurycleia from childhood). The scene ends with a kind of sleep in which Athene appears and promises to look after Telemachus but when Penelope asks about her husband, Athene refuses to be drawn. "It is idle to tell about the riddles of the wind."

The Second Scene is in Eumaeus’ hut, the old swineherd who is a faithful retainer from the old days. Odysseus arrives in the guise of a beggar and is not recognised by Eumaeus who gives him the latest news about the Hall. Soon the dogs bark again and this time it is Telemachus who has escaped the watch set for him and returned safely to the island. Eumaeus is overjoyed at seeing him and when he describes Penelope’s anxiety about him, Telemachus bids Eumaeus go and set her mind at rest. Thus father and son are left alone together. Odysseus is longing to touch his son, but does not know how to do so. Meanwhile Athene comes to the rescue: "Odysseus, make yourself known to your son." As if touched by her wand rags fall off him and a shaft of sunlight illumines him. Telemachus turns, frightened: "You are a god" - "I am no god." replies Odysseus, "I am your Father".

One can imagine the wordless duet between them. Telemachus has been brought up from boyhood to shoulder all the responsibility of having his home invaded by a band of powerful suitors who have now become his dangerous enemies and are threatening his life as well as his livelihood. At last there comes an ally, a friend to share the responsibility - a father - and what a father. Imagine the relief for poor young Telemachus. It has made him a different person over night.

And imagine it from the Father’s point of view. To find a stalwart son ready to give help in overcoming an almost insuperable difficulty.

The last Act is again divided between two scenes, the first dealing with the Suitors, the second with Penelope. At the beginning Odysseus is again this old beggar in rags, but Telemachus is confidently giving him a bowl and telling him to go round begging from the Suitors but the Suitors are wanting to know where he has come from, and why he isn’t thrown to the savage dogs rather than be allowed to interrupt their meal. Penelope comes down. She has decided to give herself to the one who has the prowess to shoot an arrow through the holes in twelve axes - a feat which she knows that only Odysseus can perform, though she does not know that Odysseus is present. When she has gone the Suitors begin immediately to try their luck, but none of them is successful. When they have all failed Odysseus asks if he may have a trial and in spite of great opposition manages to get hold of the bow - his own old bow of long ago. He is seen to have the skill of a fine archer. The Suitors look on enviously while Odysseus wins the contest, shooting an arrow through all twelve axes. It becomes clear that Odysseus has returned "You dogs! You thought that I should never return! So you wasted my house, turned it into a brothel, a drinking den! You plotted to murder my son and to force my wife to remarry while I was still alive. You feared neither the respect of me nor the gods that hold the broad blue sky."

The fight continues with the curtain down, Athene directing it from above, then Penelope’s voice is heard, from behind scenes.

"Ah, lion-head, my lion-heart,

strong and forceful,

my hero of the deep soul and the infinite, labyrinthine ways

where are you, what are you in the passing of the days?"

The Curtain rises on Odysseus resting after the fight with the Suitors. With him are Telemachus, Eurycleia, Eumaeus and Phemius. Some distance away Penelope enters quickly and stops dead, looking at Odysseus and then looking away.

"Mother, why not go up to him," says Telemachus, "why not embrace him? Your heart was ever full of stone."

"My heart is full of amazement," replies Penelope, "I cannot speak a word or ask, or even look him in the face. But if it really is Odysseus, we shall know each other."

Odysseus is guarded. Surely no other woman in the world would hold away from her man, in the twentieth year. He turns to Eurycleia: "Make my bed alone, Mother." But Eurycleia does not move. She knows her mistress too well for that.

"Strange spirit of a man," says Penelope, "I am not proud, but I remember well when you left Ithaca, the long oars flashing in the sun. Make up the large bedstead, Eurycleia which he built himself outside the wedding room." This really gets Odysseus, and again Eurycleia does not move. "Woman, why do you torture me like this? Who could have moved the bed outside the room? I built the walls round it hollowing the bed from the trunk of a sturdy olive tree that grew in the courtyard like a pillar. I stripped the leaves, planed the wood to an immovable bedpost, then inlaid it with gold and ivory. This I give you as proof, if proof you need. But I do not know if the bed is still there or if another can have cut it from the tree from which it grew."

Penelope has been greatly affected by these words. She now rushes to him. "Do not be angry with me, Odysseus because I have given you slow welcome. My heart was ever cautious, like your own, and I shuddered to think that some impostor, some false Odysseus might come."

The rest is plain duet: "Oh welcome, as the sight of land to men wrecked on the sea" in which they all finally join, in an ensemble which ends the work.

Such was the end of Homer’s "Odyssey", which makes a not unsuitable ending to a modern opera.