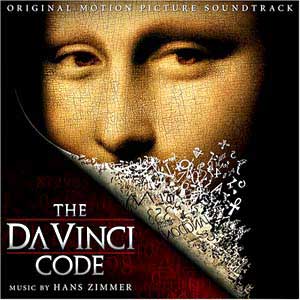

The Da Vinci Code

Music composed by Hans Zimmer

(‘Kyrie for the Magdalene’ words and Music by Richard Harvey)

Performed by a contract orchestra and choir (choir conducted by Nick Glennie-Smith) and recorded at Air Studios, Lynhurst Hall, England.

>With soloists: Hila Plitmann (soprano); Martin Tillman (cello) and Hugh Marsh (violin) with Richard Harvey (historic instruments), Delores Clay (vocals) and Fretwork (viols).

Latin lyrics and choir arrangements by Graham Preskett

Available on Decca Records (Decca 985 4041)

Running Time: 68:10

Crotchet

See also:

Hannibal Thin Red Line The Ring / Ring 2 This score, appropriate to the film’s religious theme, is preponderantly solemn, mysterious and cloistered. The orchestra is large and is supported by the forces listed above. The opening ‘Dies Mercurii I Martius’, beneath its liturgical surface, has a restless quality; and, towards the end, an explosive disruptive element that hints at a secret that could rock the Church. Little synth disturbances, and one or two banalities, spoil its effect and these carry over into the second cue, ‘L’esprit des Gabnriel’ clearly depicting malign influences in the plot but at the same time making for a less comfortable listening experience, and reminding one at one point of Goldsmith’s work for The Omen.

Classical liturgical music influences are strong: from early church modes, including Gregorian Chant (even to Respighi’s modern dressing of such music especially in the opening of the ‘Fructus Gravis’) and here one might detect other influences at work including Puccini and Vaughan Williams (Thomas Tallis). But ‘Fructus Gravis’ also contains much tense material that one might associate with thrillers scored by Bernard Herrmann. Then comes the beautiful serenity of ‘Ad Arcana’ with its beautiful harp figures and plaintive violin solo; and again Respighi and Vaughan Williams are recalled. Darker bass figures cast a shadow over the peacefulness towards the end of this memorable cue. ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ has impressive dread choral passages. The hushed yet suspense-filled atmosphere of ‘Daniel’s 9th Cipher’, another long and significant cue, features high suspended voices and treble stings with cello and violin solos and quiet but tense tripping dotted rhythm ostinatos. Then, about half way through this 9-minute-or-so cue, soft low timps and rapt string figures, then a choral entry, then the soprano voice and tremolando strings suggest a revelation. Belying its cue title, ‘Poisoned Challice’, is another lovely cue, scored for devotional male voices and soprano soloist (Hila Plitmann’s silken delivery is impresses). ‘The Citrine Cross’ brings back restless figures but beautifully orchestrated for celeste and harp. Gradually disturbing, heretical forces ascend and seem to attempt to overwhelm the devotions.

The dread music of ‘The Rose of Arimathea’ lurks dangerously in low shadows before a solo piano leads into music of poignancy with women’s voices hinting, perhaps, at the family of Christ’s journey into exile? [The cues on this CD are most peculiarly named and often give a misleading impression in part or whole]. A nagging conversation piece between a small ensemble of fiddles and larger forces repeating the same terse material is ‘Beneath Alrischa’, another interesting cue. ‘CheValiers de Sangreal’ continues this material as a quiet ostinato with growling brass interjections until a noble theme grows in intensity to overwhelm the orchestra, choir joining at the climax, suggesting the establishment and secret flourishing of a ‘Royal bloodline’.

Finally there is ‘Kyrie for the Magdalene’. A disappointment. To this reviewer’s ears, it has pretensions after Fauré’s Requiem but does not quite come off; it opens with a rather dissonant male voice drone and with soprano and voices, and only a thin organ accompaniment, continues its rather over-sweet way imitative of the French composer’s cherished masterwork.

Considering Zimmer’s lack of a formal music education, I hope I am not doing him a disservice by wondering how much of a contribution to this score was made by the arrangements of: Lorne Balfe, Nick Glennie-Smith and Henry Jackman as well as those for the choir by Graham Preskett.

A strongly liturgical-sounding score, parts of which disappoint but mostly it is very listenable - away from the controversies of that film.

Ian Lace

Rating:

4

Michael McLennan adds:-

While far from Zimmer’s best work, The DaVinci Code proves to be a more compelling album than anything one would expect from a Ron Howard adaptation of Dan Brown’s glorified airport novel. (Yes, I wish I’d written it, and accrued the royalties, but that doesn’t make it good.) Decca’s release of the score is not likely to supersede Wojciech Kilar’s score for Polanski’s The Ninth Gate (an adaptation of Perez-Reverte’s Dumas Club – DaVinci Code’s narrative template), but at least with touches of Hannibal’s sickening elegance and The Ring’s pulse-raising string writing, this album stands on its own as a unique entry in Zimmer’s catalogue. Particularly strong is the album’s second half – specifically tracks 7 through 13 – what Zimmer refers to in interviews as his DaVinci suite. ‘Poisoned Chalice’, Thomas Tallis references aside, is a particularly beautiful composition.It doesn’t quite feel strong enough to hold up as one of the composer’s best though. For one, too many sections run on autopilot. ‘Chevalliers de Sangreal’, apparently the accompaniment to one of the few exposition-free sections of the film, feels like an ensemble-specific reworking of that accumulating 16th’s idea that Zimmer has used in Mi2, Batman Begins and other recent efforts. ‘Dies Mercurii I Martius’ is the first of several cues to outline a major theme with that bombastic unison voicing that robs the composer’s work of yielding further nuances on repeat listenings. It also adds to the erroneous impression that the accompanying narrative is one of the greatest put on film. (Kudos to Zimmer for keeping a straight face on that one.) And the thrills are never quite thrilling enough. If Bruno Coulais found sufficient meat in the religiously-motivated murders of Crimson Rivers to craft a score that balanced tension well with awe of deep religious secrets, why not here, where beauty – both melancholic and joyful – is the prevailing mood.

To tell you the truth, those who want to hear a score that blends old world flourishes with modern aesthetics would be better off to go with Tom Tykwer’s score for Perfume: Story of a Murderer. It’s not that Zimmer’s score isn’t good, more that the praise it has received seems out of proportion to its importance in his own catalogue and that of the genre.

Michael McLennan

3.5

Return to Reviews Index