GEORGE DANNATT – AN APPRECIATION

Three obituaries have appeared in the national press following the death

of George Dannatt. All have paid tribute to his multiple talents, and in particular,

to his important work as an artist. This appreciation emphasises Dannatt’s

musical interests and activities.

On 17 November 2009 George Dannatt died at the age of 94 after a long and

creative life, during which he mastered and balanced three seemingly disparate

activities with distinction – chartered surveying, art and music – activities

which in the event influenced and informed each other.

Dannatt was born on 16 August 1915 in Blackheath where his father was head

of the family firm of chartered surveyors, and appeared pre-destined to join

the family firm. From the age of 11 (1926) he attended Colfe’s Grammar School

before, at 19, becoming an articled pupil to Surveyors, Land and Estate Agents

at the College of Estate Management of London University. At 25 (1940) he

qualified as a Chartered Surveyor (F.R.I.C.) and joined the family business.

Earlier, while still at school, his gradually developing interest in music

led him to become closely involved in music studies, the catalyst for which

was a 15th birthday treat when he attended a concert at the Queen’s

Hall. He heard, and was deeply impressed by, the Ravel Piano Concerto for

the Left Hand and works by Berlioz and Hindemith. Dannatt himself claimed

that this concert opened up a world and a commitment which he sought and pursued

ever after. In addition to his studies for professional examinations to become

a Chartered Surveyor he took lessons in piano, harmony, counterpoint and composition

(mainly song-writing), studying in the evenings at the Blackheath Conservatory.

He was told by Scott Goddard, who discussed the progress of his songs, saying

that while he would never be a Schubert, he might well prove to be a Hugo

Wolf.

There emerged some serious prospects for study under Michael Tippett and possibly

with Mátyás Seiber, prospects which were sadly dashed by the outbreak of war

and Dannatt’s call-up to the Army in 1940. Songs written in 1941 and 1942

were composed while on temporary transfers from the Royal Artillery into building

requisition work related to his qualification as a chartered surveyor, and

others were written prior to his discharge from the Army in 1944 on health

grounds. An important personal milestone was reached during the war with his

marriage to Ann Doncaster in 1943.

Dannatt’s first foray into music criticism also dates from the time of his

wartime service, with an article for Augener’s Monthly Musical Record

in 1943. This was the prelude for his entry into specialised musical criticism

with the liberal newspaper News Chronicle, Penguin Music Magazine and

later as a freelance writer, this at a time when most national newspapers

regularly covered music, opera and ballet in a literary and non-academic capacity.

He is said to have been a highly perceptive writer, using meticulous and informed

prose in the interest of critical integrity; he was a sympathetic champion

of modern music, particularly where he recognised honest talent in its composition.

In 1948 he was elected to The Critics’ Circle (Music Section), of which he

later became an honorary member.

Dannatt’s first steps towards life as a professional artist are probably traceable

to his pre-war interest in photography and, in particular, its application

to landscape in abstract form. Family influence may also have been a factor,

as his father had been an enthusiastic amateur photographer. Later, in 1955,

while still a full-time surveyor, he was introduced by his architect brother,

Trevor, to the artist Adrian Heath at the latter’s London studio. Heath was

prominent in the group of artists known as Constructivists, who produced work

in an abstract genre, minimal, geometric and spatial, which had derived and

developed from several different movements of the early 20th century.

Following his first visit to Cornwall in 1963, Dannatt was attracted into

the group of St Ives painters and benefited especially from his association

with the artist John Wells and the sculptor Denis Mitchell. Wells, like Dannatt,

had had a previous career – as a doctor – a fact that gave him encouragement

that a trained and disciplined mind from a “worldly” profession could form

a sound basis for creative expression in the visual arts. Initially Dannatt

had no intention of exhibiting his works, but was urged by friends and colleagues

to do so and, having joined the Newlyn Society of Artists, his first exhibition

was held in St Ives at the Penwith Gallery in 1970.

Referring to himself as a “late starter” as an artist, he could not know that

in 2009, 46 years after his first visit to St Ives, he would still be hard

at work in his studio and still exhibiting. Though reluctant to be “pigeon-holed”,

he has referred to his style as that of a “lyrical constructivist”, implying

perhaps a personal and gentler touch compared to the bold geometrics of the

“pure” constructivists, which in the view of the writer is to be found especially

in those of his works based on landscape. One is reminded too that “lyrical”

bears the connotation of song, which brings us back to the songs he had worked

on between 1939 and 1947, songs for which he had great affection and to which

he much later returned, having them privately printed and recorded in 2005/2006.

Dannatt exhibited his work between 1970 and 2008, most frequently in Cornwall

and the south-west of England, but also in London, Basel and Germany, where

he developed a particularly fruitful relationship with a gallery in the North

Sea coastal town of Cuxhaven.

The Dannatts’ friendship with Arthur and Trudy Bliss started in 1953 when

the composer and his wife visited their home, at that time in Blackheath;

the composer was already 64 years old. Bliss had been knighted in 1950 and

became Master of the Queen’s Music in 1953, following the death of Sir Arnold

Bax. They found they had much in common over a wide spectrum of activities:

music, painting, literature and life in general. Trudy and Ann were deeply

involved in the study of geology, and the four of them were frequently together

at Canterbury, the Cheltenham International Festival of Music (of which Bliss

became President) and London musical events. It was during this period, in

1957, that the Dannatts bought a cottage on the Wiltshire/Dorset border as

“a part-time residence” and after the Blisses gave up their modern-movement

house Pen Pits in Dorset in 1955, from time to time they borrowed the Dannatts’

country retreat. Bliss’s work had always appealed to Dannatt, along with other

post-Elgar British composers and although Dannatt had not yet taken up painting

in a serious way, it is tempting to speculate that an attraction was the parallels

of organisation, dissonance, intervals, space and colour present in both art-forms.

Above all, for Dannatt, the parallel struggles of the painter and composer

to achieve form from chaos, form in which both order and dissonance could

equally be present, were a driving force.

Much later, for Bliss’s 80th birthday (1971), Dannatt produced

a painting based on the composer’s Colour Symphony which was written

for the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival nearly 50 years earlier. This remains

the composer’s best-known, and probably best-loved, large orchestral work,

not counting the film music for Things to Come, and one which frequently

serves as an entrée to Bliss’s music. Dannatt has referred to Bliss’s penchant

for experimenting in tone colours, for the timbre produced through the association

of certain instruments, much as a painter has in his trial mixings. It was

while staying at the Dannatts’ cottage that Bliss was inspired by a series

of Dannatt’s paintings called Tantris to compose a major commissioned

work in variation form. This became the magnificent Metamorphic Variations

(1972); indeed Dannatt played a further part by helping Bliss to decide on

the final title. The work was dedicated to George and Ann Dannatt and in one

of the movements, actually called Dedication, Bliss made use of the

initials GD and AD to provide a further dedication in sound. It turned out

to be Bliss’s last major work and is unquestionably one of his finest, though

remaining unjustly neglected in concert and record performances.

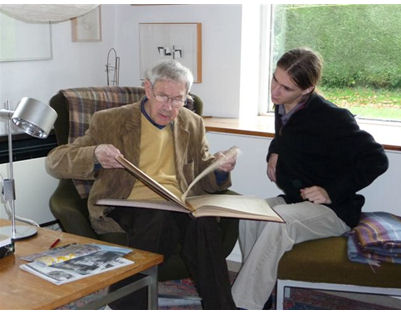

George Dannatt shows his autographed copy of the score of Bliss’s

Metamorphic Variations to a young music graduate, 2008

Cuxhaven, and in particular the Galerie Artica, became a memorable place,

not only for the Dannatts but for Trudy Bliss also. Examples of Dannatt’s

paintings appeared in three separate exhibitions there – in 1981, 1984 and

1990, the last two being one-man shows. The gallery’s owners were accustomed

to the combining of art exhibitions with chamber music concerts or recitals.

When Dannatt learned that for his 1984 exhibition no less an ensemble than

the Delmé Quartet would be engaged, he requested that the two Bliss string

quartets should be played and that he would give introductory talks. George

was to write the scripts and Ann would translate and deliver them. When Trudy

Bliss heard about this forthcoming double event, she travelled to Cuxhaven

to join the Dannatts and became completely involved with the gallery and its

owners. It was the second of these quartets that Bliss described as the best

of his chamber works. Those who know the Clarinet and the Oboe Quintets might

put them forward as worthy contenders. The two nights in Cuxhaven when the

quartets were played, with the painting display all around, remained a most

memorable experience for the Dannatts and for Trudy Bliss. A happy example,

perhaps, of the perfect synthesis of painting and music.

In 1981 the Dannatts moved from their London home in Belgravia to live permanently

in the Wiltshire cottage. Considerable changes were made to the property including

the addition of a spacious music room, which easily accommodated two grand

pianos, and the creation of an extensive garden.

When, in 2003, at the instigation and with the great encouragement of Lady

Bliss, the Arthur Bliss Society was formed, she became its President with

George Dannatt as Vice-President. Many years previously, after a chance meeting

between Trudy and the Society’s Chairman, Gerald Towell, she had introduced

him to Dannatt. George, though by 2003 almost 90, typically took an active

and serious interest in his role in the Society, frequently contributing material

for its twice-yearly newsletter and always ready to provide generous advice

and support. When Trudy Bliss died in 2008, George seamlessly stepped into

her role, but sadly for less than a year.

A view in George Dannatt’s studio, 2008

Always something to look forward to were the occasions when the Society’s

committee and guests would descend on the Dannatt home for meetings or purely

social occasions. It was always a special delight to relax in the beautiful

garden of the house in its secluded setting, a location which sometimes posed

a challenge to the map-reading capabilities of the driver! George’s conversation

was often spiced with amusing and mischievous reminiscences, with Ann proving

to be the ideal foil and companion. Any “business” would invariably be followed

by a pub lunch, then by a tour of the studio, hidden away in the grounds,

where one would marvel not only at the cornucopia of past and continuing artistic

achievement, but also at the meticulous tidiness and the total lack of clutter

that might have been expected in an archetypal artist’s lair. Was this yet

another example of the discipline of one of George’s careers playing out through

another?

David Wilby

Arthur Bliss Society

© The Arthur Bliss Society

Two exhibitions will shortly be held to commemorate the life and work of

George Dannatt:

on 17 – 28 February 2010 at the Osborne Samuel Gallery, 23a Bruton Street,

London, and

on 20 February – 13 March 2010 at the Lemon Street Gallery, Truro